Document 11074776

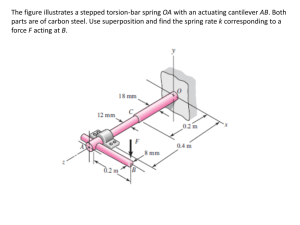

advertisement