West Virginia Educator Equity Plan June 1, 2015 Contents

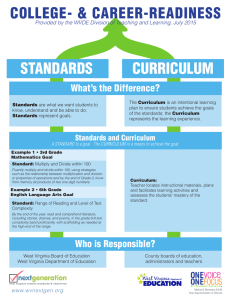

advertisement