“Integrating Effective Character Education Programs into

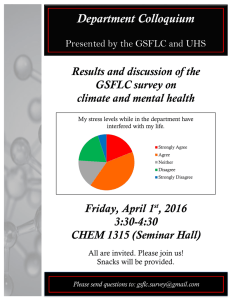

advertisement