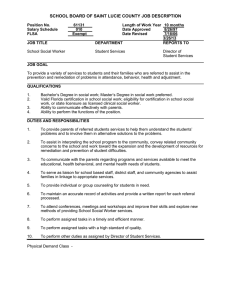

Document 11072614

advertisement

FEB S'iS88

I

ALFRED

P.

WORKING PAPER

SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT

OVERIKWESTMENT WITH RELATION- SPECIFIC CAPITAL

Rotemberg

and

Garth Saloner

Julio

J.

Working Paper #1950-87

October 1987

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

50 MEMORIAL DRIVE

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 02139

OVERIKWESTMENT WITH RELATION- SPECIFIC CAPITAL

Julio J. Rotemberg

and

Garth Saloner

Working Paper #1950-87

October 1987

Overinvestment With Relation-Specific Capital

Julio J.

Rotemberg'''

and

Garth Saloner*

October 1987

Abstract

We consider a situation in which one party (the owner) owns a

project.

He is better informed than another party (tlie worl<er) about

the payoff this project would have if investment specific to their

Initially many workers compete to be the

relationship is undertaken.

owner's partner in the project.

If the investment is undertaken the

worker gains knowledge which makes him worth more than other workers

and which allows him to capture some of the payoffs of the project

We show that the equilibrium contract generally involves

overinvestment

We consider both the case in which the owner can

credibly commit never to undertake the project with a different worker

and the case in which he can't. In the former case tliere is always

.

overinvestment.

In the latter case, there are multiple equilibria.

Overinvestment equilibria always exist, underinvestment equilibria

never exist and efficient equilibria sometimes exist.

We would like to thank Drew Fudenberg, Oliver Hart, Paul

Klemperer, Meg Meyer, Paul Milgrom and Jean Tirole for helpful

conversations and comments, and the National Science Foundation

(grants SES 8R19004 and 1ST-85101G2) for financial support.

''"MIT.

,

1

FEB

81988

When assets arc

specific 1o a particular relationship,

the

contractual forms that are feasible for governing the relationship are

crncial in determining the ability of the parties to exploit

The importance

profitable investment opportunities.

of relation-

specific assets derives from the quasi-rents they create.

These

quasi-rents are the difference between the value of the assets

current relationship and their value

such assets are instaDed,

at

least

if

to the relationship

earns less, under any original agreement, than the

By threatening

quasi-rents.

new (more favorable)

to

Once

the relationship ceases.

one party

the

in

total

vaJiie of the

withdraw from the relationship unless

contractxial terms are agreed,

that party

may be

able to Improve his outcome.

If

the original contract cannot prohibit renegotiation,

inefficient investment in relation-specific assets

in the original

undertaken

at

contract may be distorted,

all,

efficient.

Klein,

This idea

a

is

result.

a vertically integrated

market transaction would olherwise be more

central to the work of Williamson

Crawford, and Alchian (1978) who suggest that

underinvestment

will

Prices

some projects not

and others mediated within

enterprise even when

may

result.

(1975) and

in

general

For example, Klein, Crawford, and

Alchian (1978, page 301) conclude:

"...Less specific investments

will

be made to avoid being locked in".

Several recent papers have formalized these ideas.

(1984) considers the relationship between a union and a firm

latter

must decide whether or not

to

undertake

a

Grout

where the

T-elationship- specific

-

3

Efficiency requires that the firm be reimiMirsotl

investment.

the cost of the investment

the gains from

if

Grout points out, however, that

costs.

(through

excessive share of the gains once they are

invest even

it

if

is

worthwhile.

iTivestment exceed

a

its

attempt to garner an

to

reali7,ed,

may not

the firm

on the other hand, binding

If,

contracts are possible, investment will obviously be efficient

WhUe

least

the imion cannot commit

if

binding long-term contract) not

a

llie

at

1

.

binding long-term contract ensures efficiency

this

in

several authors have pointed out that efficiency can be

setting,

obtained with simpler, less complete contracts.

2

Tlic reason

is

that

farsighted agents are able to anticipate the outcome of the

anticipated bargaining and can make transfers before in\'estment must

take place that are sufficient to yield efficiency.

example,

the parties realize that the agent

if

investment

wilJ fall

ex post

transfer of $x to that pa7-1y

in

(Notice too that

partners competing for

competition

In this

tlie

among them

who must make

will

,

it

the

they can, ox a nte, agree

is

contract of this kind,

if

there are

many

is

potential noninvesting

right to participate in the relationship,

result in an offer of $x for that right.)

mutually worthwhile.

it

to a

the contingency that the investment

way the investing party can always he induced

investment when

for

$x short of recouping the cost of the investment

in the division of the spoils

undertaken.

Thus,

In

order

to

to

make the

implement a

must be possible for the third party

enforcing the contract to observe whether the investment did

take place: investment must be a contractible activit.y.

in

fact

llolmstrom and

4

-

-

Hart (1906) provide an example (along the lines of Grossman and Hart

(1986) and Moore and Hart

(1985)) that illustrates that

underinvestment can

even

investment

is

res\jlt

if

bargaining

and

efficient

is

observable to the parties, provided investment

not

is

also contractible.

While that example shows that underinvestment can result

investment

is

in addition,

IV) shows that

noncontractible, Tirole (1986, Sec.

bargaining

inefficient,

is

underinvestment

a characteristic of the optimal contract.

must undertake

if,

necessarily

s

In his model the "firm"

(unobservable

relationship-specific investment

a

i

if

to the

other party, the "sponsor") that determines the firm's costs of

producing

a

good that that the sponsor desires.

Aftei- tlie

investment

has been made, only the sponsor learns the value of the good.

parties then bargain (under incomplete information) about

firm should be paid

if

it

produces.

how

The

mvicli

the

Since mutually beneficial

opportunities are typically foregone when bargaining occurs under

incomplete information, the firm anticipates thai

full

benefits of

its

investment and so invests too

In contrast to Tirole

adverse selection

it

in

(1986)

which one

will

not reap

little.

we focus instead on

of the parties

value of the relationship prior to the time

1lio

situations of

(the "owner")

when the

knows the

relation- spe cific

investment must take place but the other (the "worker") does not.

Such an asymmetry

tlie

worker finds

project.

it

of information

more

would arise,

foi-

example, whenever

difficult to evaluate the quality of the

Then projects which

the owner would

know

to

ho

rliffei'ent

would be viewed as identical by worl<ers

seems

to characterize

many

relation -specific capital

is

An

.

of the cases in

an issne.

asymniolT-y of inforniaiion

which investment

in

For example, General Motors

might have had better information than Fisher Body about the payoff

making

their joint venture; a firm considering

investment may be better informed of

individual worker with which

considering installing cable

to the

bargaining;

TV may know

Defence, which knows how

of

new

capital

value than the union or

its

a

municipality

moT-e about

community than potential providers

Department

into a

is

it

a

the ultimate value

and the

of the service;

eacli

piece of hai-dware fits

weapons system and how weapons systems combine

defence network, has better information about the value

to

form

them

to

a

total

of

each individual project than any of the contractors bidding for the

contract.

This asymmetry of information

realized value of the project

itself

is

is

inconsequential

contract ible

case an efficient long-term contract can

simy^ily

.

Foi-

specify

of the spoils as a function of the realized value.

the

if

in

tliat

llu>

division

In practice,

however, there are numerous reasons why the outcome may not be

contractible

point which

.

Tirole (198G) contains an extensive discussion of this

we

shall not

more obvious reasons.

in

other projects

it

repeat here.

First,

if

payoffs of his various projects.

accrue

in

We merely mention three

the owner

may be impossible

to

to

is

of the

simultaneously involved

separate the costs and

Second, the payoff may

in

part

nontangible benefits that are difficult for an outsider

to

evaluate, sucli as the cffert on

of thp parties.

tlie

firms rppvitatioii or

this is

utiJitiGs

an outsidor may not know tho opportunity

Finally,

cost of funds or other inputs the parties commit to

if

llio

common knowledge

to the parties

even

project,

tlie

themselves.

With the exception of adverse selection the situation we study

is

the canonical one in this literature.

participation of the worker

ventvire.

order

in

The events unfold

in

to

The owner requires the

carry out his proposed

three stages.

In

owner bargains with the worker over the terms

tho first stage,

the

of an e x ante contract.

Once hired, however,

that

makes him superior

any replacement and which therefore, ex po st,

to

worker acquires training

endows him with some leverage.

the second stage,

the owner must decide whethor to undertake a

gains from the investment are realized and,

ex post bargaining ovpt

We

in

the third stage,

there

tiiose gains.

restrict attention to the case which w(^ believe to be of

bargaining position ex an te.

we assume

that the

We formulate

complete-information setting.

(198,3)

is

conducive

In the second,

the stronger

ways.

at the first

jinte identical.-^

discussion that this ass\miption

in

is

this in two

owner can bargain

many workers who are ex

Takahashi

he does so, the

If

most practical importance: where the informed owner-

first

that

With the specific worker in place, in

particular investment he has under consideration.

is

knowledge

ot-

In the

stage with

Recall from the above

to efficiency in the

as

in

Sobel and

and Fudenberg and Tirole (1903), the owner makes

take-it-or-leave-it offer to a specific worker- before investment takes

a

-

7

place.

Examples where the

When

are

workers

a firm is hiring

many workers with

Ex post

first

to

formulation

work

similar skills

in a

appropriate abound:

new

factory, e x ante tliere

who are competing

for the job.

however, the workers acquire specific human capital which

,

allows them to acquire some rents which

the plant.

partner

is

to

depend on the productivity

of

consider the case of an inventor who needs a

Similarly,

supply inputs.

Ex ante there may be many

potential such

suppliers but only one inventor.

Particularly in this case of ex ante large numbers, the

formalism of the three stage model neglects

Such

feature of real world contracts.

a

a

potentially important

model implicitly assumes thai

the owner and the worker are able to form an exclusive relationship

in

the sense that the owner can credibly promise that he will not engage

in the project

because

in

in

our model

incorporates bolii

a

it

is

relationship,

Where

it

lump-sum payment

is

This

generally optimal to design

whether he invests or not) and

investing.

any other worker.

the future with

a

to the

payment

n

is

important

contract that

owner (independent

that

is

of

contingent on his

impossible to specify an exclusive

the "noncontractible projects" case, an incentive

is

introduced for the owner to abscond with the lump-sum payment and then

solicit

an offer anew from another worker.

owner may find

it

Indeed an

ini

scrupulous

profitable to go into the business of colJecting

lump-sum payments without ever investing.

This would be a

particularly attractive option for an owner with

a

very unprofitable

8

-

investment opportvinity

There are

contractible.

An example

similar businesses

which

a variety of

is

and where

circumstances

in.

Investment by

wlvirli

it

manufacturing process might be

way

in

from other projects the owner

particular

in a

in

is

new engine

this category.

however, the project may be contractible.

not

is

several

in

difficult to specify the

is

GM

project

a

where the owner operates

a particular project differs

involved

in

other cases,

In

For example

a

project to

provide a cable television service to a city or the automobile bodies

for an automobile

producer are easily definable.

venture one partner may be able

specific line of business will be

Our focus

is

to

promise thai

Similarly in a joint

all

conducted via the

his efforts in a

joint

venture.

mainly on the contractible projects case,

Our

formalized by the three stage model.

result in this case

unambiguous: the optimal long-term contract leads

relation -specific capital.

to

is

overinvestment

This results despite the fart that

it

in

i^s

possible to structure a contract that leads to efficient investment.

When

the contract

undertaken when

undertaken yields

it

is

is

structvired so that projects are only

efficient to do so,

the average project

a positive payoff to the relationship.

Since

bargaining yields some of this surplus to the worker, competition

at

the first stage forces workers to offer a lump-sum to the owner for

the right to participate in the relationship.

However, since workers

cannot distinguish owners with good projects from those with bad, this

lump-sum payment must be paid even

to

an owner who

in

fact

has

a

bad

who has no

project and

intention of investing.

particularly attractive to an owner

who

has

fact

in

outcome

Sucli an

a

is

not

good project

since he shares some of the potential spoils with his unattractive

Indeed, such an owner would prefer a lower

counterparts.

payment and

higher payment made contingent on investment (which he

a

intends to undertake)

this kind,

lumpsum

they

.

Since workers are happy to oblige an owner of

will offer

the preferred contract.

But then the

higher investment -contingent payment induces overinvestment.

Althought the focus of the paper

on the contractible

is

projects case,

we

We model

by extending the horizon beyond three periods and

this

briefly examine the noncontractible projects case.

enabling the owner to offer the project anew to

previously contracting with another.

a

worker

aftoi'

Not suprisingly, multiple

equilibria arise in this case.

We are able

underinvestment cannot arise

in

show, nonetheless, that

to

equilibrium and provide sufficient

conditions for tho outcome to involve strict overinvestment.

The second formulation

bargaining power

is

where he

offer to a specific worker.

of Sobel

is

\u

which the owner has relatively more

able to

In the

make

absence

a take-it -or-leave-it

of discounting,

tlie

models

and Takahashi (1983) and Fudenberg and Tirole (1983) feature

such take-it-or-leave-it offers from the informed

to the

In this case there are again multiple equilibria.

Of these, one

yields the efficient outcome while the others

overinvestment.

by the owner

all

uninformed.

involve

Moreover, those with overinvestment are

to the efficient equilibrium.

all

preferred

10

We are

not

tlie

first

to

demonstrate that relation-specific

capital can lead to overinvestment.

this

is

possible in his model

if

Tirole (198G,

investment

is

Sec.

V) shows that

observable.

This

occurs because investment alters the parties' relative bargaining

strength.

The

Idea that investment alters bargaining strength

central to the analysis of Grossman and Hart (1986).'^

also

is

Crawford's

(1982) model has the same ambiguity in that both under- and

The ambiguity there

overinvestment are possible.

arises for a

he considers risk -averse workers who

completely different reason:

wish to intertemporaUy smooth consumption and may therefore dislike

the contract that gives efficient investment.

In a

Webb

arid

paper addressed

to a

rather different question De Meza

(1987) also derive an overinvestment result.

an investing firm which must borrow to finance

its

Tliey consider

setting differs fundamentally from ours in that the investment

specific,

and

in

Their

investment.

is

not

that binding contracts can be signed before

investment takes place.

Indeed the faUuro

that drives their results

is

in

the financial markets

the presence of limited liability and the

impossibility of observing the true value of the project, even ex

post

.

Despite this large contextual difference, their model

somewhat

similar to ours in that there

is

is

adverse selection and that

the financial institution (which corresponds to the worker in our

model) expects to earn more on projects that are

in

fact

good.

this expectation that leads the financial institution to offer

contracts that are sufficiently attractive that even poor quality

It

is

11

projects are undertaken in equilibrium.

However, their result

in

some

sense derives from the fact that they do not allow for the possibility

of

payments which are not contingent on investment actually taking

As discussed above, we consider such

place.

in ovir

analysis and they

turn out to play an important role.

The paper

is

organized as follows.

the case where there are large

Section

of potential

1

Ex ante large numbers

workers while

in

of

Section

We begin by

the payoffs.

workers

recalling the timing structure,

The owner has

a project

an amount K

and by describing

which yields G

if

if

owner can enter

into a contract with a particular worker.

is

second stage, investment specific

ends.

K

is

expended.

If

In the third stage,

verifiable

We

III.

participates and

if

in

Contractible projec ts

(i)

place

we analyze

we examine take-it-or-leave-it offers by the owner.

11

present our conclusions

I

numbers

In Section

by

a third

invested.

to thai

a

worker

In the first stage the

owner and

1h;il

In the

worker lakes

investment doesn't take place the game

G

is

learned by the worker (but

is

not

party) and the owner and worker bargain over

its

division

The outcome

of this

game depends on what

be contracted on at each stage.

First,

is

known and what can

we assume throughout

thai

the

third stage payoff cannot be contracted on in the first stage so that

ex post bargaining (we use the generalized Nash bargaining solution)

12

is

The

the rule.

due

to a

inability to commit to third stage payoffs could be

One

variety of factors.

activity the

worker

is

that the actual

carry out cannot be specified

to

is

possibility

advance so

in

the worker can threaten to hold out after the investment takes place.

Second, we assume that the contract can be made contingent on the

owner/worker

specific investment taking place.

This

possible

is

can be verified (by the Courts) that the owner invests K

specific capital.^

The

and central assumption,

third,

is

if

it

the

in

that the

owner knows G exactly while the worker only knows the distribution

F(G) from which G has been drawn.

owner

in

is

many

assumption

make

In

is

that the

owner.

that emerges between

workers when

we suppose that they make offers

of them,

at the first stage.

willing to

final

a better bargaining position than the

To capture the competition

there are

The

owner

to tlie

These offers specify payments the worker

is

exchange for becoming involved with the owner.

With contractible projects and investment there are two such payments

that can be made.

The

first

owners who actually invest.

The second

which the owner promises never

different worker."

is

Thus

to

investment

in

and V

is

is

a

a

payment L

in

to

exchange

undertake the investment with

general an offer

in

an amount paid by the worker

later takes place,

payment V which accrues only

a

is

to the firm

is

whether or not investment

contingent payment that

for the equilibrium offers.

problems of this kind, we solve

it

a

!L,V}, where L

a pair

is

made only

fact takes place.

We now solve

for

As

is

usual for

by backwards induction.

If

the

if

13

third stage

reached, there

is

bargaining

is

information:

iindei- full

sunk and the surplus G must be divided.

capital costs are

The

generalized Nash bargaining solution to this bargaining problem

mazrmlzes Pq^""?^" (where Pq and P^^ are the payoffs to the owner and

worker respectively) subject

payoffs

restricted to equal G.

is

sum

to the restriction that the

The

'

of the

third stage payoffs to the

owner and worker are therefore (l-a)G and aG respectively."

Now

consider the second stage and suppose that the owner has

accepted an offer of {L.Vj.

independent

of

is

received by the owner

whether investment takes place, the owner finds

investment worthwhile

will

L

Since,

if

and only

(l-cx)G

if

V

+

>

K.

Thus the owner

undertake any investment for which

G

Thus an

>

(K-V)/(l-a)

=

gV.

offer of {L,V] that

G^, such that only investments

cutoff are undertaken.

(1)

accepted results

is

is

The higher

Is

the lower the cutoff.

V,

is

received

in

In

the event that

undertaken the more projects are undertaken.

Consider the

and suppose that an accepted offer

first stage

Then the amount

involves a contingent payment of V.

expects

a ciitoff,

that yield a return higher than the

other words, the higher the payment that

investment

in

to receive in the continuation

f

[aG-V]dF(G)

G^

=

f

gV

game

aGdF(G)

is

-

that the

worker

given by:

V[1-F(gV]

Since competition between workers ensures zero profits for the

workers,

(2).'

it

must be the case that L

is

given by the expression in

We can thus characterize the contracts by V with L being

(2)

14

determined by (2).

Furthermore, we can restrict attention

from (1), this

since,

is

V<K

an implication of nonnegative G.

Of the possible values of V, which one (with

L from

to

To examine

(2)) will be offered in equilibrium?

corresponding

its

this question

consider a proposed JL,V! equilibrium contract and an owner for

G>K under

Since such an owner

that contract.

the worker wishes to enter into a relationship,

that there

prefer.

fixed,

is

most-preferred contract amounts

to V,

subject to (1) and (2).

d0/dV

implies that

low.

I,

is

+

1

-aGVf(GV)dGV/dV

=

[K-GV]f(GV)dGV/dV

will

negative.

selecting his

maximizing i^(V)=L(V)+V with respect

=

Extremal solutions, which

and since K and G are

,

Thus

L+V.

owner would

aii

This gives:

dL/dV

=

to

sucli

L+V-K + G(l-a)

his preferences are increasing in

whom

must be the case

it

no other breakeven contract which

Since such an owner earns

the kind with

is

whom

-

[1-F(gV)1

+

+

Vf (GV)dGV/dV

F(gV).

+

1

(3)

be considered below, arise when (3)

This can happen, for instance, when

by equating

Interior solutions are obtained

(.S)

to

a

is

zero which

gives

[K-gV]

=

Since the right-hand-side

overinvestment

F(GV)(l-a)/f(GV).

is

positive,

(4)

we have K>G^: there

is

in equilibrium.

The second-order-condition

for a

maximum

is:

d20/dv2=[K-GV]f'(GV)[dGV/dV]2 + f(GV)dGV/dV-f(GV)[dGV/dV]2<O, or

[K-GV]f'(GV)-(2-a)f(GV)<0.

15

In

order

to interpret

and the overinvestment result

(3)

let

us

consider a proposGd [L,V| equilibrium contract and suppose that a

worker wishes

to

improve upon

the worker wants to

In particular,

it.

design a contract that, compared to the proposed fL.Vi contract, has

the effect of inducing the marginal investment not to be undertaken

whUe

not affecting the Inframarglnal investments.

the amount of investment that

undertaken

is

contract will have to have a slightly lower

same time,

at the

inframarginal,

to

thai

order to reduce

new

equilibrium, the

V than

before.

In order,

be as attractive to an owner whose investment

owner must be kept as

the decrease in

this,

in

In

well off as before.

is

To do

V must be matched by an exactly equal increase

in L.

So consider the effect of increasing L by

by

|f

$1.

There are two effects:

(GV)dGV/dV

I

when V

First,

is

decreased by $1,

Note however that, by definition, the owner

breaks even on the marginal projed

This moaTis thai the efficiency

.

gains that result from the abandonment of marginal projects

to the

first

worker.

term

in

These gains from the decrease

(3).

The second

effect

is

would not have undertaken the project

The probability

thus an Increase

V

whiJe reducing

The marginal such

fewer projects are undertaken.

project loses [K-G"].

$1

that the

owner

in the

payment

is

in

to a

Any owner who

any case receives

of this type is

accrue

V are given by the

distributive.

in

all

F(gV).

$1 more.

There

is

noninvesting owner of $F(G^)

.

If

[K-GV]f (G^)dG^/dV exceeds F(G^) then the worker gains from the change

since he can induce every investor to accept his

new contract.

16

With this Intuition in mind

(3)

why

-

is

it

easy

to see directly

from

the equilibrium contract cannot involve only efficient

Investment.

In the efficient case

vanishes and we are

$1 while increasing

left

L by

K=G^

with F(G^)

$1 has a

efficiency of investment that

.

so that the first term in

At the point K=G, reducing V by

second-order effect on the

undertaken.

is

However

order effect on the lump-sum payments that are made

owner who does not invest,

(3)

In other

has

a first-

to the

type of

it

words, resources are sqviandered

on the kind of owner whom the worker does not wish

to attract in the

Although increasing V induces some inefficient

first place.

investment, this has the effect of enabling the worker continue to

attract owners with good Investments

sum payment.

because

it

The reduction

In

whUe

offering them a lower lump-

the lump-sum payment

is

desirable

applies not only to owners with good investments,

but to

those with bad investments as well.

We now show

that the above equilibrium

renegotiation between the

robust to

signing and the undertaking of the

At this point the owner has already received L so that

Investment.

when

initial

is

the payoff

is

between

G^ and K

both parties

to the relationship

could be made better off by agreeing not to go ahead with the

Investment.

The gain from cancelling the contract

gain

in

is

split

worker a(K-G).

therefore,

the usual way,

To implement

the owner must net

is

K-G.

If this

(]-a)(K-G) and the

the outcome of this renegotiation,

the worker must offer the owner (l-a)(K-G) not to invest.

This would require the worker to know G, however.

If,

as

we

17

have assumed, G

is

unobservable, the worker mvist offer an amount

the owner not to invest thai

is

AU noninvestors would now

to

Suppose the worker

independent of G.

Then investors would receive

offers M.

before.

-

as mvich as they received

receive an additional M.

This

would have exactly the same effect on investment decisions and on the

payoffs of the worker as increasing L in the original contract while

leaving L+V unchanged.

Since the

worker could not improve

that the

has no effect on the outcome.

initial

optimal contract ensured

his lot in this way,

renegotiation

This occurs essentially because

owners accept the contract so that

Its

all

acceptance yields no

information that can improve the allocation.

This argument demonstrates that our original equilibrium

robust to renegotiation.

equilibrium even

fact that

It

also implies that this

when renegotiation

is

is

the only

is

This results from the

allowed.

were there any other equilibrium with renegotiation, the

worker coul offer our equilibrium contract instead, knowing

would be accepted by an investing owner and

Ihal

it

that

i1

would be robust

renegotiation

We now consider the

effect of an increase in a,

the share of

the ex post benefits that accrues to the workers, on the efficiency of

investment.

Intuition would suggest that such an increase

makes

overinvestment more severe since efficiency obtains when a

Indeed, when the second order conditions obtain, there

relation

between

a

and eqviilibrium G^ (assuming

can be obtained by differentiating (4):

it

is

is

is

a

zero.

monotone

interior)

which

to

18

dG^/da

Up

=

[K-GV]f(GV)/{(l-a)3d2,^/dv2i.

now we have considered

to

possible that di^/dV

is

of the form

is

[0,V'i

witli

is

In this

associated

Combining

.

(1)

given by:

G'' Is

(2),

it

has L equal to zero because more attractive contracts

it

with negative L's will not be accepted by noninvestors

and

Yet,

positive even for L equal to zero.

case, the equilibrium contract

cutoff G'';

interior solutions.

\

a[G-G''']dF(G)

[1-F(G'''][K-G"1

-

=

(5)

G"

Since the first term

smaller than

K

in

so there

also apparent that

G

'

is

positive,

is

(5)

the cutoff value

overinvestment.

falls

when

a

must be

G''

Differentiating (5),

it

is

rises so tiiat the extent of

overinvestment diminishes.

might be asked under what circumstances extremal solutions

It

are likely to emerge.

In other

words when does

(3)

imply that L

negative so that nonivestors are unwilling 1o participate.

occurs

F(G'')

if

is

Indeed,

G''.

is

there are a great

in this

effort,

case (3)

that,

is

likely to

contrary

to

is

very costly

be positive even for

all

so that F(0)

individuals

of a worthless project

is

will

which

G^

Then

(3)

equal to

witho\it

is

Then, as long as

1,

is

choose to become owners of such projects

arbitrarily close to one and f(x)

arbitrarily small.

worker.

to the

endogenous and that essentially any individual can,

become an owner

so that

our assumption, ownership of projects

indistinguishable from worthwhile projects.

positive

This

projects with G loss tiian K,

high, and any lump sum transfer

Suppose

itself

many

is

is

positive for

all

foi-

x positive

positive

G^ and

is

tlie

19

thp unique equilibrium.

Is

{0,V'''}

distributed

,

it

is

If,

G

instead,

uniformly

is

straightforward to show that the interior solution

when more than

applies

-

half the projects are worthwhile while the

boundary solution applies otherwise.

The extremal

occurs for two reasons.

equals -l/(l-a)

is

(5)

a low a

First,

Second,

holds, K-G*^

zero L implies that

If

This also tends

small.

is

if

(3).

to

is

a

equal zero,

it

important

is

which the incentive for the owner

to

to

consider

abscond with

rise to an infinite horizon

that achieves this

is

to

to invest,

in

general, include

payment and an investment-contingent component.

assume that

the game

This gives

a

lump-sum

Here, however, the

lump-sum component does not automatically create an exclusive

relationship. ^^

is

lump-

game with no discounting but with complete

As above, contracts can,

interest

a

an offer anew from another worker plays a

solicit

second stage the ownei' decides not

Our

a

unambiguously positive.

is

begins again with workers making new offers to the owner.

recall.

zero so

reduce the

Indeed, for

so that (3)

not contractible

is

The simplest modification

at the

when L

Noncontractible Projects

sum payment and

role.

in

K equals G"

the project

a setting in

means that dG^/dV, which

low n means that,

a

importance of the negative term

(ii)

This

a is low.

small in absolute value so the negative term of (3)

is

relatively small.

that

when

solution also tends to arise

not

equilibria that can arise.

in

fully characterizing the possible

Rather, our concern

is

with the

-

20

conclusions that can be drawn about the amount of investment that can

occur

The

in equilibria.

underinvestment

point to note

first

in equilibrium in the

sense that an owner whose G

exceeds K must eventually Invest. H.

Suppose,

to the

The reason

is

the following.

contrary that, the best project actually undertaken

has a payoff G" which

to

that there cannot be

is

is

Define, for any equilibrium,

above K.

be the net payoff of the projects which

Z(t)

be undertaken after

will

the t'th round of the game but which have not yet been undertaken by

Then, Z(t)

the t'th round.

Therefore, for each

This means that

at

t,

T

is

there

is

obviously nonincreasing

a

T such

the owners of

expect a payoff no higher than

all

that Z(T)

t^^

smaller than

at

T, there exists

owners whose project yields less than G" who would prefer

the offer {0,aKj to continuing with the original equilibrium.

such an offer,

if

z.

projects can collectively

Therefore,

e.

is

in

to

accept

Yet,

Thus there

accepted yields profits to the workei-.

cannot be an equilibrium with G" greater than K.

Our remaining findings

contract which nets an owner

rely

who

offer

is

accepted.

{0,V'''l

the observation that

tio

actually invests less than V'' will

actually be accepted in equilibrium.

an offer

oti

To

see this,

suppose that such

Since the owner could Instead have accepted the

which workers are always willing

to

make,

it

must be the

case that the owner intends to earn more than {0,V''j by absconding

with the lump-sum component of the offer.

Thus workers would

not

this offer.

This observation has two consequences.

First

It

Implies that

make

21

when

the solution

is

!0,V'''l

(the extremal case)

are noncontractible.

it

is

in

the contractible projects equilibrium

also the unique equilibrium

The reason

is

that,

when projects

there

this case,

in

no

is

contract which nets more to an investing owner while letting workers

break even.

The second

implication

contractible projects equilibrium

parameter values for which

all

that,

is

is

interior,

previous section implies that there

which

is

V larger than aK

is

equal to aK

is

range

of

some {L.Vj combination

(since overinvestment

preferred to fO.V] by investing owners.

is

a

Interiority of the solution in the

guarantee that the contract {L',aK! where

isn't,

there

in the

the equilibria without contractible

investment feature overinvestment.

positive L and

even when the solution

preferred to [O.V'l; Indeed

L'

it

is

witli

assured)

is

This does not

V

given by (2) with

often

is

When

not.

it

equilibria with noncontractible projects involve

all

overinvestment. This occurs because, to obtain efficient investment,

owners would

L' + aK is

lets

liave to accep^t contracts

lower than

V,

there

workers break even that

Thus

is

will

whoso V equals aK

no offer whoso

be accepted

prefers the SL',aK] contract to the

To

equilibrium.

The range we have not considered

interior solution in the three stage model

in

equals aK and which

for a wide range of parameter values there

overinvestment.

show that

in

V

this

when

Yet,

.

is

is

strict

where there

is

an

and the investing owner

iO,V''=}

contract.

range the efficient equilibrium

is

It

is

easy

sustainable.

to

-"^^

gain some understanding of the relative importance of these

22

ranges we consider the case

mentioned above (0,V'j

is

in

which G

is

then the most attractive contract

{0,V'''!

so that

preferred to [L'.aKj

is

if

we are not

and only

if

less

if

Even when more than

than half the projects are worth undertaking.

half are worth undertaking,

As

uniformly distributed.

in

the extremal case,

less than two thirds of

the projects are worth undertaking.

Ill

Tak e- it-or-leave-Jt offers by the owne r

A

workers

different method for eliminating the bargaining power of the

is

to

put the informed owner

it-or-leave-it offer to the uninformed

particular,

of

B

the owner offers to invest

This method

to him.

is

in

the position of making a take-

worker

if

attractive

at

when the workers are

cannot be a lump sum payment such as L.

sum payment by the firm

firm makes

is

if

it

The

is

will

rejected

If

simply be turned down.

it

the offer

level of transfer,

in

some

any

for such a

B, that the owner

to the

is

lump

Tlie offer the

is

payable only

accepted, investment takes

We analyze the pure strategy

signalling game.

in

doesn't.

from the worker may signal something

value of G.

is

In

There thus

Any request

thus a request for a transfer R whicli

investment takes place.

place,

unable

is

carry out the project with some new worker.

to

stage.

the worker makes a transfer

sense already employed by the firm and the owner

event

first

tlie

willing to accept

worker about the true

equilibria of this

Although there are multiple equilibria, several

properties that any equilibrium must satisfy can bo readily

if

-

23

established

First,

if

B

aK the offer

>

an owner offers aK, G must equal

lose

by making the

to

at least

earn aE(G|B)

expectation of G given an offer of B.

at least

K and

B, where E(G|B)

-

Thus,

if

is

offer of

the

B equals aK, E(G|B)

owner wUl never

of this result is that the

ask less than aK since he can be sure to gain more by asking aK.

second consequence

he

will

is

that there cannot be underinvestment

By asking aK, an owner can earn (l-a)G

always undertake an investment for which G

There exist other signalling equilibria.

between

G''

and K, there

investments whose

is

G exceeds

given G' in this range

These offers as

is

the worker has nothing to lose by accepting the offer.

The consequence

equilibrium.

If

K, for otherwise he would

On the other hand by accepting an

offer.

B the worker expects

be accepted by the worker.

will

is

+

in

Therefore

aK.

K.

>

Indeed, for

a signalling equilibrium in

which

all

G'

all

The equilibrium

G' are carried out.

supported by offers equal

well as smaller offers are accepted,

A

to

for a

K- (]-a)G'.

larger offers are

rejected

To

see that these are indeed equilibria,

owner who makes an equilibrium

a)G', which

Is

positive

if

He earns (l-a)G

offer.

and only

G

if

consider first the

> G'.

So,

-K+ K-(l-

owners whose G

exceeds G' benefit by making these offers and gain nothing by making

smaller offers.

On

the other hand owners with G<G' will

offers which will be rejected.

make larger

Therefore

a

worker who accepts the

K

+

(]-a)G'.

offer of K-(l-a)G' earns aE(G|G>G')

-

This gain

is,

24

-

given (5), nonnegative as long as G' >

It.

exist,

G'''.

worth noting that, not only do overinvestment equilibria

is

they are extremely desirable from the point of view of the

owners whose bargaining power

assumed

is

to be strong.

Specifically,

owners prefer equilibria with higher transfers so their most preferred

equilibrium

the one where

is

all

projects whose

G exceeds

are

G''

undertaken.

We now

briefly consider what would

happen

if,

instead of

giving the owner the right to make take-it-or-leave-it offers in the

first stage,

we endowed both players with

more closely resembles that

difficult to

there

is

know what outcome

to predict

bargaining strength that

stage of our game.

It

is

suggestive

is

to

is

from such bargaining since

a dearth of extensive form models analyzing this case.

possiblity which

stage,

in the third

a

imagine that, even in the

One

first

the two parties are trying to divide the benefits of the

relationship with a fraction a going to the worker. This can be

achieved by letting V equal nK

is

The owner then invests

.

positive so that efficiency prevails

importance of the change

in

^'^

.

if

(l-a)(G-K)

This points to the

bargaining strength between stage one and

stage three for our overinvestment results.

IV Conclusions

Our main conclusion

is

that adverse selection creates a

tendency towards overinvestment.

investment

is

Moreover

in

the important case where

contractible and there are ex ante large

numbers

25

overinvestment characterizes the unique equilibrium contractual

relationship.

That optimal contract has the feature that

sum payment

model

is

it

requires a lump-

for the exclusive right to the particular project.

correct we ought to observe such payments.

In

many

such as cable television franchises and military procurement,

uncommon

of the

we would argue are characterized by our assumptions,

situations which

not

our

If

to see substantial

supply the good

in

question

.

is

it

lobbying efforts for the right

to

Provided the granter of that right

Municipality or the Defence Department in these examples

beneficiary of these efforts, then the

initial

-

is

-

the

a

lobbying can be

interpreted as the lump-sum (noncontingent) payment in our model.

Besides the wining-and-dining that

rent-dissipation process,

is

usually part and parcel of the

such benefits might also include

uncompensated design work,

feasibility analysis,

and consumer surveys

performed by the lobbying firm.

In order to higlilight the effect of adverse snloction on

overinvestment, we have made some strong assumptions.

our discussion

in

Section

II

suggests that the asymmetry

bargaining power may be necessary for the result.

in

For example,

in

initial

Similarly,

Grossman and Hart (198G) or Tirole (1986), investment

if,

as

itself is not

contractible a countervailing tendency towards underinvestment arises.

Finally,

our assumption of efficient bargaining

is

clearly important.

Suppose, for purposes of Illustration, that bargaining dissipates some

fraction,

say

t,

of the gains

from

a project.

Then we should replace

26

G by tG

in

our analysis.

example,

it

is

-

In the contractiblo projects case,

then immediate from equations

could be underinvestment in equilibrium.

as

T

approaches unity there

and

(1)

This

be no investment

will

that there

(4)

fairly

is

for

obvious since

Thus

at all!

while

the presence of bargaining leads to overinvestment, costs of

bargaining move the outcome

We

close with a

in

the opposite direction.

comment on the implications

if

the costs of organizing economic activity are

different within the firm than

arms-length contracting

integration

1"^

.

our analysis

That analysis

for the traditional aniysis of vertical integration.

asserts that

of

is

markets then situations

in

inefficient

may give

which

in

rise to vertical

This raises the question of the incentives for

One common way

vertical integration in our model.

this is issue is to

of thinking

suppose that the firm faces a trade-off

in

vertical integration decision.

On

may remove

the third stage (and replace

the bargaining

authority relationship), bu1

in

its

the one hand, vertical integration

on the other hand,

,

about

Uioi-o

it

with an

may bo some

inefficiency involved in carrying out the transaction "in house".

If

bargaining

that was the case,

is

then owners for

whom

the third -stage

particularly costly would have a strong preference for

vertical integration.

These are the owner's for whom G

is

high.

An

equilibrium of a model with endogenous vertical integration and

contractible projects might therefore have two cutoffs instead of just

one:

Owners with projects

project "in house".

that

exceed the

higliei- cutoff

Those with projects below

thi.s

would do the

cutoff would offer

27

their projects In

market as

tlie

in

-

our model.

'llic

second cutoff would

divide these projects into those that are undertaken

and those that are not.

self -select out of the

remains

On

is

in

Since the owners with the best projects would

market, the adverse selection problem that

reduced and the overinvestment that results

the other hand,

equilibrium

is

less severe.

some inefficient vertical integration then coexists

with the market's overinvestment.

28

FOOTNOTES

1

Williamson (1983) shows that efficiency obtains with binding

contracts

if

(and only

if)

transfers that are valued equally by both

parties can be made.

2

This argument

contained, for example,

is

in

Hart and Holmstrom

Grossman and Hart (1986), and Milgrom and Roberts (1987).

(1986),

what WUliamson (1975) refers

3

This

4

Tirole (1987) provides an example that illustrates

is

overinvestment can arise

5

This

is

a stronger

in

to as

ex ant e large numbers,

how

their model.

requirement than requiring that investment

spending be verifiable since

it

must also bo verifiable that the

investment which took place

is

specific to this

The investment must

owner and

worker.

this

not be sucli tlial the ownoj- ran benefit

liy

excluding the worker.

6

it

If

will

this

amount L

be accepted by

is

all

positive at the equilibrium contract offered

owners regardless

of their G.

noninvestors would never take a contract whose L

means that contracts with negative

L's

is

By

contrast,

would only have payments

investors and can be lumped together with contracts whose L

With this proviso, we can view L as being paid to

7

See Roth (1982), Grout (1984).

This

negative.

all

owners.

is

to

zero.

29

8

there

imniGdiate from this that,

is

It

is

underinvestment

investment

if

In this case

.

it

is

is

noncontractible,

not possible to

make

transfers which are contingent on whether investment

first stage

actually takes place.

Yet, investment

is

the owner will only invest

So,

socially worthwhile as long as

investments for which the payoff

is

G

(l-a)G

if

K.

>

Thus,

> K.

between K and K/(l-a)

will not

be

undertaken even thougli they are socially worthwliile.

9

workers knew G, the expression

If

projects

then forces V to equal aG

10

It

.

(2)

would be aG-V for

Competition between workers

which investment takes place.

in

The owner then gets (l-a)G-K + aG

Therefore he invests

invests.

in

if

G exceeds K and

might be asked why workers ever offer

why owners do

put differently,

and then pursue

this is that

has once accepted

a

lump

to

svim

associated with a bad project.

lump sum component or,

another worker.

draw the inference

sum transfer L

The reason

that an

So,

for

owner who

payment and then not invesled

is

in fact

while the payment of L doesn't

necessarily exclude other workers in the future,

in

efficiency results.

not simply take the lump

a relationship with

workers are free

a

he

if

it

may make workers

the future more reluctant to deal with this particular owner.

11

there

This

is

riiles

out the only conceivable form of underinvestment when

no discounting.

If

the payoffs from agreements in later

rounds are discounted relative

could say that there

does not invest

at

is

to the

payoffs from the

underinvestment

if

first

an owner whose

the first available opportunity.

It

is

rovind one

G exceeds K

possible to

30

-

construct examples of such delay when the future

as L"

+

aK

In the latter case Z

all

discounted as long

V''.

any given round either some investments take place or none do.

In

12

bigger than

is

is

unaffected while in the former Z

is

falls

since

the projects undertaken have payoffs in excess of K.

13

This can be done as follows.

Workers make offers

any owner who has not yet accepted an

offer.

of !l,',aKl

Owners who accept one

G below K.

Once again, owners have no

incentive not to accept the offers and those whose

have

to offer a positive

than

L'

+

aK.

If

G exceeds K

will,

For a deviating worker to attract an owner he would

inve.st.

in fact,

a

lump sum components because

worker deviated

in

this fashion,

V'''

is

{L'.qK! to an owner

Workers would be willing

who has spiirned

owners spurn deviators.

Thus

to

He would

extend the offer

a deviating woj-kor

the owner

is

smaller

the owner would

accept the offer but would not invest regardless of his G.

then request new offers.

borause

strictly better off

all

by not

investing with deviating workers.

14

In the case in which a

discrete

number

of values,

is

one half while the G's can take only

this solution

is

identical to the one

obtained by applying the axiomatic approach of Harsanyi and Selten

(1972) and

15

Myerson (1984).

Although

literature,

it

is

this is

commonly asserted

of

They

these offers and do not invest are not extended further offers.

are viewed as having a level of

to

to

be the case

questioned by Grossman and Hart (198G).

in

the

a

31

REFERENCES

Crawford, Vincent: "Long-Term Relationships Governed by Short Term

Contracts"

International Center for Economics and Related

Disciplines,

London School

of Economics,

Theoretical Discussion Paper

1982

82/59,

De Meza, David and David C. Webb: "Too much Investment: A Problem

Asymmetric Information," Q uarterly Journal

1987,

of

Ec ono mics

,

102,

of

May

179-22.

Fudenberg, Drew and Jean Tlrole: "Sequential Bargaining wilh

Incomplete Information," Review of Economic Studies

,

50,

April 1983,

221-48.

Grossman, Sanford

J.

Ownership: A Theory

Political

Economy

,

94,

and Oliver Hart: "The Costs and Benefits

of Vertical

of

and Lateral Integration," Jou r nal

of

August 1986, 691-719.

Grout, Paul A.: "Investment and Wages

Contracts," Econometrica

,

52,

in

the Absence of Binding

March 1984, 449-60

Harsanyi, John C. and Reinhart Selten: "A Generalized Nash Bargaining

Solution for

Two-Person Bargaining Games with Incomplete Information",

32

Management Science

,

18,

80-106

1972,

Hart, Oliver and John Moore,

"Incomplete Contracts and Renegotiation,"

June 1987, mimeo.

HoLnstrom, Bengt and Oliver Hart: "The Theory of Contracts,"

Advances

Bewley,

Klein,

In

Eco nom ic Theory, Fifth World Co ngress, ed. by Truman

New York: Cambridge University

Press,

1987.

Benjamin, Crawford, Robert and Armen Alchian:

Integration,

in

"Vertical

Appropriable Rents and the Competitive Contracting

Process," Journal of Law and Economics

Milgrom, Paul and John Roberts:

,

October 1970, 297-32fi

21,

"Bargaining and Influence Costs and

the Organiz.ation of Economic Activity," Research Paper Series No.

GSB Stanford

93'1,

University, January 1987.

Myerson, Roger B.: "Two-Person Bargaining Problems with Incomplete

Information," Econometrica

,

52,

March 1984, 461-488.

Roth, Alvin: Axiomatic Models of Bargaining

Verlag,

New York: Springer

1979.

Sobel, Joel and Ichiro Takahashi:

Review

,

of

"A Multistage Model of Bargaining,"

Economic Stu dies. 50, July 1983, 411-27.

33

Tirole, Jpan

Economy

.

:

94,

.

"Procurempnl and RenQgotiation

April 198G,

"

,

Journal of Politica l

235-59.

Theoretical Industrial Organization

,

1

987

,

mimeo

WUliamson, Oliver: Markets and Hierarchies: Ana ly sis and Antitrust

Implications

,

1975.

.

"Credible Commitments: Using Hostages to Support

Exchange," American Economic Review

,

73,

September 1983, 519-40.

U53ls

059

Date Due

Lib-26-(;7

MIT LIBRAHlfS

3

^Oao 005 135

3t0