Document 11072538

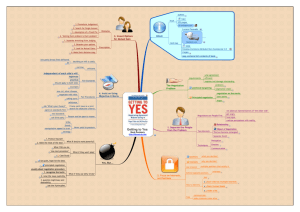

advertisement