Document 11072055

advertisement

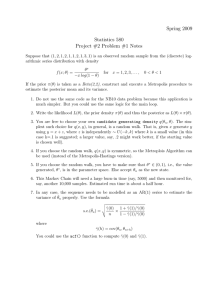

UD2G ALFRED P. WORKING PAPER SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT RISK AND LARGE-SCALE RESOURCE VENTURES Horst Siebert WP #1816-86 MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 50 MEMORIAL DRIVE CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 02139 RISK AND LARGE-SCALE RESOURCE VENTURES Horst Siebert WP #1816-86 I Risk and Large-Scale Resource Ventures Horst Siebert* Large-scale resource ventures are characterized by high set-up costs, a gestation period of five, seven or ten years and period of operation in which the benefits of a long project come in. large-scale ventures require an innovation Very often, a in tech- nology such as the development of offshore-oil platforms and exploration, drilling, and transportation under arctic conditions. environmental impacts may occur, and in some cases, Moreover, irreversibilities may exist Finally, in the competing uses of nature. private and social benefits may diverge. Future bene- fits must be weighed against the initial costs, with benefits occurring at Benefits and a later date and being discounted. some of the costs are uncertain. gy, to initial, disruptions, Risk relates to the technolo- operating and closing costs, to price and revenue and point of view to changes in taxation, from a to environmental private firm's regulation or even ex- propriation. All these different types of risk account for the possible outcome that the huge initial financial outlays may be lost, In i.e. the different types of risk make up financial risk. this paper we look at the role of risk in large-scale pro- jects. At the outset, risk is defined and different types of risk for large-scale projects are described. We then discuss the impact of risk on the profit of mine when we consider a a single agent who is owner and sponsor at the same time. We then analyze approaches to risk management and risk shifting when second agent is introduced. If we allow for more than and for different types of risk, as a two agents risk allocation can be described complex net of contractual arrangements. Finally, some limits of risk shifting are pointed out. The meaning of risk Risk means that the implications of mined ex ante. Variables affecting or factor prices or technological the occurance of a decision cannot be deter- a a decision such as product relationships are random, specific value of a variable depends on of nature which cannot be controlled by an individual variables of interest to the agent diverge from a i.e. state a agent. The mean on both sides with the mean being defined as the expected result or as the mathematical variance of possible results. Normally, assumed that the agent can attribute probabilities to of outcomes, i.e. dom variables. he or she knows a a it is variety density function for the ran- Probabilities assigned to the variables may be based on objective observations, such as past experience or a multitude of observations, or they may reflect personal judgements. The variance of a specific variable may be relevant to one agent, but not to another. Consequently, risk can only be defined with respect to the objective function of an agent. The variance of the price of a natural resource may mean resource-extracting firm or for a different risk for a consumer; or it a implies diffe- rent risks for producers with a diverging risk attitude. Moreover, the relevance of a variance in a specific variable depends on the set of constraints of an agent. a natural resource has a A given variance in the price of smaller risk for a country, if the coun- try not only exchanges the resource against consumption goods but if it has accumulated financial assets. Or assume that a resource country uses part of the resource in production at home. Then the probability of a fall in the resource price will hit the country's export earnings, but industrial activity at home may be stimulated due to lower resource prices. In the capital asset pricing model, the relevance of the constraint set for the definition of risk pointed out by the fact that the relevance in the variance of is a specific variable depends on the portfolio of an agent. More spethe risk of an investment cifically, of an economic decision) or profit is or more generally (an asset measured not by the variance of income from the specific investment but the variance of income from the portfolio caused by that investment. Risk is primarily dependent on the covariance of the return to the specific investment with the return to the total investment of instance, a a portfolio. For fire insurance has an uncertain outcome the payment varying between the value of the houses in the case of fire and zero (Lind 1982, p. 60). this risky investment makes the over- But all portfolio more certain. The variance of variable may not be especially relevant for an a individual agent due to options of shifting the risk within the given set of restraints. More important is that the risk of an individual agent may be shifted to someone else for whom the variance in a with weight variable does not present such in the tail source represents a a for risk. falling price of a risk for a a a A variance natural re- resource-export ing count ry . similarly skewed probability distribution is an but , insurance to resource- import ing country. The shifting of risk therefore important method of risk reduction. relating to public goods, riable in question is in Risk, can only be shifted if the variance of a variable im- plies different risk for different agents. for risk an Institutional arrangements of risk sharing are of utmost importance for risky projects. however, is a a i.e. This no longer hold social risk. If the va- public good like air quality, variance that variable "must be consumed in equal amounts by all" (Sa- muelson 1954) and risk cannot be shifted. The analysis of the impact of risk overlaps with the discounting of future benefits and costs. of risk requires thus making to a a As a rule of thumb, the existence risk premium in addition to the discount rate project less profitable. But this rule only relates risky benefits whereas risky future costs require tion of the interest rate, a substrac- and the rule only holds under very specific assumptions (Lind 1982, p. 67). Moreover, the discount rate chosen determines the impact of risk of future periods. From the above interpretation of risk, the paper has First, which are the variables of large-scale lines of attack: ventures that show specific variance? Second, a three to what extent can single agent adjust to the variance in these variables? Third, by which measures can the risk of large-scale ventures be reduced if more than one agent is considered and what is the role of risk sharing? Types of risks The decision problem of a private resource firm in the case of a large-scale venture boils down to the question whether the initial financial outlay. period profits can be recuperated by the present value A, which are discounted with the discount rate where T 6t n TT (t) dt The firm maximizes the present value of profits Q = - A + n (1) H 5 of subject to a of constraints such as set the finite stock of re- capacity constraints of production, operating cost sources given, functions etc. Typically, the firm initially chooses the level of capacity and the extraction profit over time. Nearly all the factors influencing the viability of demand, such as costs, large-scale resource venture a the price of substitutes are associated or with different degrees of uncertainty. Thus, different types of risk can be distinguished. The cause of the uncertainty problem of large- Financial risk. scale ventures divisible, is large-scale ventures are technically in- that that very often they cannot be developed step by step and that they require a huge initial outlay that the risk of being lost. dom variable. If faced with is The present value of profits the firm provides Q is exposure to the financial risk may threaten the existence of the firm if the project is a risk of financial ruin. ran- the financial outlay itself, for instance from retained earnings, There a fails. Moreover, heavy financial ex- posure may impede access of the firm to financing in the future thus limiting its options for growth (Walter 1986). The financial outlays involved in some large-scfle resource pro- jects are shown in Table 1 and 2. Table 1. Setup Costs for Large-Scale Energy Ventures (in billion U.S. dollars) Project Setup Costs Locat ion 40-50 Alaska Gas Pipeline 4800 miles Alaska Midwest German/Russian Gas Pipeline 3600 miles West SiberiaRep of Germany 15 Athabasca (Tarsands) Alberta 13 Planned but shelved Under const ruct ion . Canada , State of the Project Cancel led during p Woods ide ( Gas Northwest Shelf, lann ing phase 11.9 Produc ing 10 P 10 Cancelled during Aus t ral ia Liquified Natural Gas N Rundle (Shale Oil) Austral i ger i a- France i a lanned pi ann ing phase Norway Gas Deal Trans-Alaska Pipel ine (Oil) 789 miles North Sea 8.2 Prudhoe Bay-Valdez, Alaska Planned 8 Constructed Ekof i sk North Sea 6.7 Producing Colony Shale Oi Colo rado 6 Cancelled Northwest Dome Quatar 6 Planned will be developed at 1 ower level 5.5 Produc ing of 5.5 PI anned Trans-Canadian Pipeline (Oil) North SlopeChicago 5.3 Not available Brent Field North Sea (United Kingdom 5.2 Producing (Gas) Upper Zakum Field Abu Dhabi Oil Coal Refinement Fed. Rep. Germany ; 8 Project Setup costs Locat ion State of the Project 3.5 Producing 2.5 Planned North Sea (Statf j ord-Emden 2.3 Constructed Gas Pipeline 1080 miles Hasse R'Mel (Tunisia-Bologna (Italy) 2.26 Cons t rue t ed Cathedral Bluffs Project (Shale Oil) USA 2.2 Producing Gas Pipeline 604 miles North Sea (Statfjord-Scot land) 2.03 Planned Brae Field North Sea (United Kingdom) 2 Producing North Sea 2 Produc ing North Alwyn (Oil) Field Project North Sea 1.83 Under con- Coal Project Venezuel 1.5 Planned Tern Field North Sea (United Kingdom 1.47 Postponed Beryl North Sea (United K ingdom) 1.29 Produc ing Austral 1.13 Feasibility Study El Cerrejon Coal Mines Col umb Brown Coal Hambach, Fed. of Germany Gas Pipeline Statfjord C i a Rep. Oil Concrete Platform Field Roxby Downs Uran ium) ( s i a t rue t ion Data collected from newspaper reports and from Walter (1986) and transferred into U.S. dollars according to prevailing exchange rates Data verified on the basis of Financial Times International Year Book (1984), Oil and Gas 1985. . Table 2. Setup Costs for Large-Scale Ventures in Mineral Industry (in billion U.S. dollars) Projects Locat ion Setup Costs State of the Project Carajas (iron ore; other minerals; costs estimate including mine, township, railroad, port) Brazi New aluminium smelters (including hydrology) (Projected in several countries) 2.5-3 PI Ti tan ium Aus 2. 12 Planned Guinea 1.5 Planned Papua New Guinea 1.32 Produci ng Port land Victoria, Aus t ral ia 1.3 4.9 Under const ruct ion t r al i a anned (5000 tons/year) Mi ergui-Nimba bauxite OK Jedi (Go'ld / Copper) Ium i n i um Plant (500 000 tons/year) A , (Gold) First stage constructed; next two stages shelved Iron ore mining facilities Wikuna vanadium Cerro Matoso Nickel Gunning Bijeh Copper Pi Ibara, 10 The financial risk is influenced by other types of risk. Note that the classification of the types of risk used here does not prevent over lappings . Revenue or price risk. High capital outlays and a long gestation period mandate that the product of the resource-venture sold in the market over long period of time. Thus, the existence reduce costs per unit. The project may be faced with the risk that the product cannot be sold or that the price is uncertain. Demand may fall off at some point in time either due to in being implies large volumes of production in order of high fixed costs to a is a change demand behavior or due to new sources of supply. Price may also vary cyclically (mineral resources). Cost risk. a A foreseeable trend of cost increase, however, does not repre- sent a risk. in risk arises when operating costs vary irregularly; Examples are changes in capital costs, in wages, freight rates and technological miscalculations leading to increased operating costs. Unforeseen environmental impacts may cause an increase in cost in a given setting of environmental New regulation and additional environmental constraints policy. imposed at point for a a later period in the life of the mine are cases in variance closing costs of a in costs. Cost risk may also relate to the mine or to the investment costs at the start when institutional restraints increase time costs for obtaining a permi t 11 Supply risk. Some large-scale ventures such as electricity plants require a permanent stream of inputs and thus face the risk of supply disruption. Completion risk. The long gestation periods involved in largescale ventures give rise to the completion risk if unforeseen technological problems arise, if the leading contractor does not deliver on time or if the process of obtaining more time than expected. a permit involves If the time schedule can n-o t be hold up, cost overruns will occur. To these predominantly economic risks, technological, geological, environmental and political risks must be added. Technological risk. When large-scale ventures duplicate known technical solutions, ing a the technological risk is negligible (open- new copper mine similar to one already existing). When, however, an innovation in size take place or when new technical solutions have to be found (Antarctic, Sea Bed Mining, North Sea drilling in retrospect), Moreover, the "hard" the technological solution may fail. technology component involves complex inter- dependencies and the possibility of failure. Exploration and resource risk. possibility of failure mine is operating, in A specific technical risk exploration. Moreover, is the even when the the resource stock and its properties (quali- 12 ty) under an area of land or sea may not be well known (geologi- cal resource risk). Environmental risk. Resource extraction tends to be pollutionintensive or may have terms of air, in land and water pollution negative environmental impacts. With large-scale ventures representing new technological approaches, not all environmental effects of resource-extraction nay be apparent at the outset. "Un- expected side effect may evolve during the period of resourceextraction. The externalities perceived by the Permit or acceptance risk. policy maker or by the public influence the institutional setting of resource-extraction. in the case of back- stop technologies in the industrial nations, some technologies For instance, like atomic power plants may have may not be received, high, a low risk acceptance. the time costs of obtaining and the stipulations of a a permit A permit may be permit may be changed over time. When risk acceptance remains constant over time, the large-scale venture will meet the acceptance risk very early in process. in A change in risk acceptance, however, will imply a change regulations for resource-extraction and resource use that will only become apparant at ing the planning a a later stage of a project thus represent- risk for the large-scale venture. Taxation and Regulatory risk. Taxes such as the corporation in- come tax and other business taxes influence the rate of return of 13 large-scale ventures. This is especially true for the taxation of extraction such as extraction license fees, resource rent taxes, and extraction taxes. A change in taxation redefines the condi- tions for the viability of a a project. The same argument holds for change in regulation. Expropriation risk. Besides taxation, the property rights relating to the extraction of the resource, represent a very important determinant of large-scale investments. The property rights for resource-extraction may vary from securely defined leases auctioned off for the highest bidder via profit sharing arrangements to nationalized industries relying on foreign technological and management expertise via subcontracts (Barrows 1981) Government risk. Finally, the government may change either by having a cases, taxation and contracts may be altered. new party in power or by some type of a coup. In both The last three types of risk have also been summarized under the heading of political risk and if they are specific to as a country country risk. This term suggests that countries can be classi- fied according to the constancy of their institutional setting or resource-extraction including such factors as taxation, pro- fit sharing arrangements and stability of governments and political sys t ems 14 T h e^_ijn p a c_t _o f In r i s J<_ f o r_ t h e ^ p o n so r- owner order to analyze the role of risk for venture we first develop a in one person. retained earnings. large-scale resource the operator and the supplier Capital for instance is provided from Assume that this agent faces risk for his resource, a given price the risk being distributed identically and independently over time. of financial a frame of reference in which we assume only one agent being the sponsor, of capital as JL _? J-P gle ag ent The price risk gives rise to the risk loss. How will the single profit-maximizing agent react to risk? He will adjust the profit-maximizing control parameters of his maximization problem from equation 1 in such a way that the variance in the resource price becomes less relevant. What are some of the options available for risk reduction of the single agent? Diversification into the future. If the price risk buted identically and independently over time, reduce the impact of a is distri- the firm can given variance in price on the present value of profits by shifting revenue into the future, i.e. by postponing extraction. Future revenues are less risky because they are discounted and the present value of the risky revenue is reduced. Diversification into the future becomes more in- teresting with a higher discount rate. Of course, this approach 15 is more promising if the price risk however, reduced over time. the price risk rises over time, Thus, risk. diversification into the future a the risk does not in political only applicable is increase over time. Moreover, uncertainty of a variable may arise in different periods mine. Note also reduction in the present value of the price risk due to a discounting may be overcompensated by an increase if If, the increase in the offset the impact of discounting. price risk may that is in the life of the One may be able to reduce some type of uncertainty at an early stage (geological resource availability) whereas other types of uncertainty such as environmental risk may only appear over time. Reduction of size of investment. vestment not is If the initial size of the in- determined by technical considerations, an in- crease in the variance of price would mandate to be used for a longer period of time. a lower capacity The longer duration of the use of the capacity represents a diversification into the the lower future; initial investment reduces the risk of finanif the price risk cial loss. Again, over time, the firm can adjust by not by a a longer use of the capacity. (or political risk) lower initial investment but A increases special case arises if the project can be partitioned into several stages. Then investment can be partly stretched into the future reducing the risk of fin- ancial loss . . 16 Portfolio of projects. A firm may diversify its risk by under- taking projects with different risk characteristics. Thus, a high technological risk in one project may be offset by a technological risk in another project. Or exposure to poli- tical risk or country risk in pensated by a project in a developing country may be com- a country with Information and learning. Risk a low lower country risk. a due to non-existing or un- is certain knowledge. The gathering of information is therefore an important method to reduce risk. geolo'gical or explo- Thus, ration risk can be lowered by geological studies before explo- Technological risk may be reduced by similar ration starts. operations on project in a smaller scale or by simulating the large-scale computer models. In the case of environmental risk, good policy to reduce unexpected externalities and it seems to sincerely check them out at the outset of the planning pro- cess. in It a may also be helpful to let local groups participate the planning process political risk of (open planning) change in regulation. a mulating experience by operating a other way to increase information. i.e. as a in order to reduce the Learning, i.e. large-scale facility, For a accuis an- given level of risk, given variance in some of the relevant variables such price, the sponsor-owner maximizes profit by adjusting his control parameters to the given risk. creases paramet r i cal 1 y . be affected by the level Assume now that risk in- Then the present value of profits will of risk. Let a represent a measure of risk such as the variance in the price of the resource or in 17 environmental damage. Let a the variance in the price as increase for instance by increasing a random variable for each period. Then expected period profits become less certain, ed present value of profits will be reduced. Thus, and the expectit realistic to assume (a) Q Equation Figure 1 2 is with Qa < 0, illustrated in Figure < 1 (2) is rather 18 With risk increasing, reduced. At a level d and for a zero, , is the expected present value of profit is the project a, > the expected present value of profits is not viable. In Figure has been assumed that the firm faces a variance of the resource price, the set of risk policy that it 1, given variance such as a in- struments is given and that the firm maximizes the present value of profits. The firm then can reduce risk to a level a*. Profit maximation implies that all avenues of risk reduction open to the firm are used. Note that the relation between the present value of profits and risk as is also influenced by the stock of resources given, a number of parameters such the capacity constraint and ope- rating costs per period so that the curve shifts with these parameters . Equation ment r 2 being defined for means that to reduce risk a a given set of risk policy instru- change in the policy set will enable the firm and thereby increase profit. The change in the policy set may be brought forward by the individual firm as an innovation, or it tutional setting. of future markets, may be produced by variations in the instiFor instance, the existence or non-existence rules for long-run contracts or imperfections of the capital market relevant for the firm. influence the set of policy instruments 19 Risk _s h i f t_i n^ _^i'__?.__^_^ ^_9_Q.?' ^S ?^^ The single agent has not too many options to accomodate risk. order to analyze how risk shifting works we now introduce for instance agent, of a random variable relevant Let x be for a reduction in the variance the maximization problem of the random variable such as a second supplier of capital. a Risk reduction can be interpreted as firm. a In price or cost per period and let f(x) a period profit, revenue, represent the probabilities of distribution for a given period prior to the action of the firm. Risk reduction takes places if by some action of the firm the variance in the random variable is reduced so that longer relevant for the maximization problem, but now the relevant random variable with a x x^ distribution function is denotes g We have g (xf This transformation of figure in 2 where a quadrant III. = ) a (^ [ f(x), r no ] relevant variable is illustrated in simple linear relationship has been assumed (x^). , 20 »(«) Figure Thus, 2 risk reduction can be formalized as a = a(r) , a < 0, a r It is > (3) r r realistic to assume that applying the policy instrument implies progressively rising costs with V = v(r) , V < r 0, V > (4) r r Define profits as G = Q [ a(r) ] - v(r) (5) T 21 we have dG/dr = Qa - a v r (5a) r and d2G/dr2 = Qoaa2 + Qaa r according to the assumptions. i.e. as in if Qa ar figure > 3. 1 \ vr for some r r T, V < (5b) r r If G can be increased by using f, risk reduction can be illustrated 22 It worth while for the firm to use is increase profits. Since f reduces risk, T levels of profit with risk. up to in P* figure order to associates 3 The Qr-curve can be interpreted as the willingness to pay curve for the shifting of risk, as a In reality, demand curve for risk shifting. fic firms. to i.e. the policy instrument An important case T can take a variety of speci- point for large-scale ventures is in limit the financial exposure of the sponsor and to shift part of the financial risk to the supplier of capital. A firm may re- duce its exposure to financial loss and at the same time reduce its price risk by having a capital the most simple case, supplier join the venture. the financier may provide a percentage In p of initial financial outlays and may receive an equal percentage of period profits. Under this assumption, equation 5 can be simpli- fied into G figure 3 let defined for < In (P) = (1 - [a Q p) the policy instrument p < 1. capital. curves as shown in figure p* < be the percentage 3 can be interpreted firm to bring in foreign The firm can reduce its risk and increase the present value of profits by increasing, < f Then Qr in figure the marginal willingness of the as (p)] 1. 3, p from a zero-level, and with there will be an optimal p* with 23 In figure though the probabilities ,for future profits of the 2, project are not affected, a the profit expected by the firm shows different probability distribution around a given period. For the firm, the variance of reduced, and it can increase initial investment, profit sharing in profits is lower mean due to a and shorten the life-time of the mine.^^ capacity, contribution of equity financing consists financial loss to the individual agent; scale venture is reduced, at least in i.e. The important reducing the risk of the lumpiness of a large- from the financing aspects. The basic point of risk shifting is that by shifting the risk to someone else, the producing firm can increase its profit by re- ducing its risk. With the risk policy variable to the level of risk a in equation may also be drawn as a function of 3, a T being related the Qa-curve in figure as figure in 3 The Qa-curve 4. represents the willingness to pay for the reduction of risk indicating the increase in profits per unit of risk reduction. When the firm can shift risk level a*. only with a (curve SS). It the risk free of charge, is demand side faces willing to pay a give up a a a price risk and if the supply risk (risk of disruption), risk premium BB' risk going through B'. terested in increasing with the level of risk instance a relates to a will choose the quite realistic that risk will be taken over risk premium AA' If for it If lump sum amount AA' may be its curve of willingness to bear the demand side long-run contract, it is not specifically in- the resource firm may have to per unit of risk the demand side into a long-run contract. In in order to induce figure 4, both par- 24 ties derive benefits from risk allocation analogous to producer's and consumer's rent. Figure Ris^k In 4 allocation in a complex net of contractual arrangements reality, many agents are involved in large-scale ventures: the project operator making the investment and operational de- cisions, sponsors providing some of the capital, access to market, know-how and contractors responsible for construction, suppliers of inputs, banks and other financial institutions, the government defining the right to extract the resource, 25 granting permits of operation and specifying taxes, as well as international organizations and the customer. The different types of risk are allocated to the different agents in a complex net of contractual arrangements. The main question for the role of risk in large-scale ventures is: How are the different types of risk allocated to the different agents involved? Which institutional arrangement allows the shifting of risk? Can these institutional arrangements reduce the risk of the main sponsor, i.e. increase his profits and make a large-scale project viable or more profitable. In the following we review some of the most important instru- ments of risk shifting: Limits on financial exposure. putting a Financial risk can be reduced by limit on financial exposure. This can be achieved by shifting the risk to equity capital as already discussed and by establishing a vehicle company separating the risk of the large- scale venture from the sponsor's balance sheet (Walter 1986). The financial risk can be further reduced by bringing in additional sponsors thus spreading the risk on many shoulders. Shifting financial risk to banks. The project operator can reduce his financial risk through project finance. Banks provide part of the capital taking over some of the financial risk. ture periods the price will be paid, fall the banks may loose part and principal of their If in some fu- and interest cannot investment. Cofinancing . 26 from international organizations another way to reduce finan- is cial risk Supplier and customer credit. The supplier of an input may provide a credit order to stimulate his sales, in case of machinery or when a either in the large-scale venture uses a perma- nent stream of the input (coal in electricity generation). customer may be willing to provide future deliveries. be linked to In this case, The credit to be paid off by a customer credit likely to is long-run sales constract. a Shifting set-up cost to the resource country. Price risk and the financial risk can be shifted by reducing initial outlays for the' right extract and then receiving only to the price which is random. In shifted by moving away from lump sura a theory, a concession with service contract. option of risk shifting, however, In a a large initial toll per barrel con- the real world, likely as a contract risk). this increases the political risk of a change in taxation schemes or in the contract cense bargaining, portion of the price risk could be payment to production sharing, tract or even a It risk management policy. is (obsoles- therefore rather un- Moreover, the historical change from concession of the 1960's to the more recent forms of contracts such as the a t o 1 1 -per-bar re 1 arrangement reflects change in the property rights and in the bargaining position vis-a-vis risk assignment. 27 Completion guarantees. Completion risk can be reduced by completion guarantees from the leading contractor and by stand-byletters of credit from banks (Walter 1986). Avoiding contract risk. Contractual arrangements between resource countries and international resource firms face the risk of "obsolescence bargaining" are in a (Vernon 1971) due to the fact that the firms strong bargaining position prior to exploration and in- vestment whereas their bargaining position is severely weakened after investment has taken place. Moreover, in, there is a growing pressure in the resource country to change the taxation or royalty scheme and thus This danger of with revenues coming to revise the contract. change in the contract may be reduced by extrac- a tion arrangements such as toll per bar r e 1 ' con t rac t s and the re- source-rent tax in which the resource country takes over some of the price risk. Long-run sales contract. run sales contracts. In Price risk can be reduced by using longthat case, the variance of the price may be completely eliminated for some quantity or at least be reduced, depending on the specifics of the sales contract. The variance for the price over the total reduced. Future markets, two years, play a quantity in though limited a given period will be in time depth of one or similar role as long-run contracts. Whereas the choice of the time profile of extraction and of the initial level of investment are at the discretion of the firm, one can see that 28 the decision on long-run contracts depends on the willingness of the partner on the demand side to enter a long-run contract Downstream integration. Under specific conditions, firm may a be able to reduce price risk by vertical integration. Such an approach could be followed if downstream products are less volatile in price or more specifically, would open up in a if downstream activities secure line of production (chemical products the case of an oil producing firm) whose price has tive correlation with the oil price. however, Note, a that negathis policy requires additional financial outlays, and though the price risk may be reduced, Of course, the risk of financial loss may rise, vertical integration may be spread over time thus allowing the reduction in the risk of financial loss. Integrated risk management. Although the different types of separate risks mentioned above partly overlap, they may arise simultaneously thus increasing the variance the present value of profit. The increase tal and technological in in the price risk, in environmen- risk eventually augment the variance of expected profits. Therefore, different policies of risk management may be called for simultaneously. Institutional arrange- ments are required that reduce several risks such as the risk of financial risk at loss, the risk of technological the same time. A case in point is failure and price the Russian German gas deal where German banks provided the financing, a German and other international steel producers delivered the pipes and other tech- 29 nological equipment and where a long-run sales contract reduced Russia's price risk. Risk allocation can be interpreted as arrangements or a system of contractual a set of risk markets for the different of risk and among different participants. tracts are interlinked in the sense of a types The different con- general equilibrium model. Successfully shifting completion risk to the leading contractor implies an a reduction impact on financing. stomer or to a in financial risk and may have Allocating the price risk to the cu- government also reduces financial risk and re- quires lower risk premiums to be paid to banks. the most important agents, the different approaches to risk reduction. Figure 5 shows types of risk and some OTHER SPONSORS SPONSOBI FINANC AL I CONTRACTOR COMLETION GUARANTEE STANO-BY-LETTER OF CREDIT GOVERNMENT GUARANTEE Figure 5 31 Figure suggests that relatively high transaction costs are 5 involved in organizing the contractual arrangements between the multitude of agents involved. With markets for allocating the risks not clearly established some international banks pro- vide project financing as risk management a financial package or an integrated (Walter 1986). 2) The limits of risk shifting Figure indicates how 4 agents, and figure 5 a specific risk illustrates ments and risk allocation among a is allocated between two net of contractual arrange- multitude of agents. There are, a limits to risk shifting and to institutional innovations however, Risk shifting is not that allow to shift risk more efficiently. possible if the willingness to pay for the shifting of risk and the willingness to take over risk against a Risk shifting can only occur if the parties benefit from it. There must be a premium do not match. involved all derive rent for the demand side in the sense that not the total willingness to pay for shifting is required as payment in must be a rent premium paid risk. is a a risk contractual arrangement. And there for the supply side in the sense that the risk higher than the internal costs of accepting the a 32 Consider figure 4. Risk shifting curves do not intersect. In is Figure not possible 4, the two if the variance in vari- a able is assumed given and the question is studied how the given risk can be shifted. ramet r ically Increase now the risk of for instance its price variance. , curve in figure 1 willingness to pay shifts downward implying is a definitely reduced for rametrically increased risk does not imply fit with a unit of risk shifted, figure likely. will shift to the left, 4 A a project pa- a Then, the profit lower a*, o > a* . i.e., the the pa- If larger gain in pro- the willingness to pay curve in and risk shifting becomes less similar result holds if the producing firm has higher a risk aversion. If the willingness to accept the SS-curve in figure 4 risk against premium a will shift upward making clearing risk allocation less likely. Such a the supplier of risk bearing is facing less which allow him to take over only a a is reduced, • market situation arises if favorable restraints lower level of risk or if he becomes more risk averse. Private risk and social risk may diverge. In such a case, a re- source project may not take into account all risks that accrue to society. Consider for instance the case of environmental risk which due to existing and anticipated regulation in the profit calculus of firm it a firm. a whole is not optimal. not included From the point of view of the shifts the risk to the public, society as is So and risk allocation in for risk allocation and risk 33 risks related to an externality should be internalized. shifting, Social risk cannot be shifted, but it can be reduced by the agent to whom attributed. is it Take the risk of environmental dis- Environmental quality being ruption. public good, a definition no way to reduce the risk by shifting person. Only if the assumption of a it there is by to another public good is given up and a regional dimension of public goods introduced, is can risk of different regional public goods be pooled. Note, however, when properly internalized, social risk, ternal measures of a firm, i.e. that can be reduced by in- by pollution abatement. Conclusions The viability of ence of a a large-scale venture pected profit a reduced by the exist- variety of risks such as price risk, and environmental risk. that is a All technological risk, these different types of risk make ex- random variable and give rise to the possibility the huge initial financial outlay necessary for setting up large-scale venture may be lost. Some of these risks may be re- duced by internal adjustments such as the time profile of extraction or the be shifted. level of initial A investment, and some of the risks may demand curve for the shifting of risk is derived. The resulting risk allocation depends on such factors as the risk attitudes, the amount of variance initially given and the options available to the firm and the supplier of risk bearing to reduce and transform the risk internally. In reality, many agents are 34 involved and risk allocation must be understood as of contractual arrangements. scale venture may diverge, Social risks, complex net Private and social risks of a large- and social risk should be internalized so that social risks are reduced by internal firm. a however, adjustments of the cannot be shifted. 35 Footnotes • Paper to be presented at the "Global Infrastructure Fund" workshop on "Global Infrastructure Projects", Anchorage. I am grateful for critical comments by J. Keck and J.E. Parsons ^' In the familiar (i-a-diagram, the for individual agent, portfolio financing) X a thus shifting the position of (efficient prior to the innovation of project to the tion space between left n Lessard and Paddock, 2> project financing reduces (X') and allowing a new transforma- a as shown in the diagram (Agraon, 1979, p. 305). and Note that project financing and the lurapiness of largescale ventures represent an argument for compensatory trade as a specific aspect of a financial package which the market may not be able to provide. . 36 Re fe re n ces Agmon, T., Lessard, D. and Paddock, J.L. (1979), Financial Markets and the Adjustment to Higher Oil Prices, S. in R. Pindyck (ed.), Advances in The Economics of Energy and Resources, Greenwich, Conn., 291-310. (1981) World Petroleum Arrangements 1980 Vol. Barrows Inc. II, New York Brennan, J.M. and Schwartz, E.S. (1985), Evaluating Natural Resource Investments, Journal of Business, 58, 135-157. Financial Times International Year Book (1984), Oil and Gas 1985, Longman, Old Woking, Garnaut, R. and Clunies Ross, Rents. Oxford: Leland, Surrey. G.C. (1978), A. (1983). Taxation of Mineral Clarendon Press. "Optimal Risk Sharing and Leasing of Na- tural Resource, with Application to Oil and Gas Leasing on the OCS", 413-438. Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 42, 37 Lind, R.C. (1982), Primer on the Major Issues Relating to A the Discount Rate for Evaluating National Energy Options, Lind et al. Discounting for Time and Risk R.C. in Energy Policy, Baltimore, sity Press, Long, (eds.) in N.V. Art", 21-94. (1984), "Risk and Resource Economics: The State of Risk and the Political Economy of Resource De- in: velopment, ed. New York 1984, Miller, M.H. John Hopkins Univer- London, by Pearce, D.W. Siebert, / H. / Walter, I.; 59-73. and Upton, C.W. (1985), A test of the Hotelling Valuation Principle, Journal of Political Economy, 93; 1-25. Palmer, K.F. Mineral Taxation Policies in Developing (1980), An Application of Resource Rent Countries: Tax. IMF Staff Papers 27, 517-542. Pearce, D.W. (1984) et al., Resource Development, Pindyck, R.S. (1980), Risk and the Political Economy of London: MacMillan. Uncertainty and Exhaustible Resource Markets, Journal of Political Economy, 88; Pouliquen, L. (1979), Baltimore. 1203-25. Risk Analysis in Project Appraisal, ' 38 Reutlinger, (1980), S. Techniques for Project Appraisal under Uncertainty, Baltimore. Samuelson, (1954), P. A. "The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure", Review of Economics and Statistics 36, 387-389. Siebert, (1984), H. Pearce et al., D.W. in; "The Economics of Natural Resource Ventures", eds of Resource Development, Vernon, R. U.S. Walter, I. R. , Risk and the Political Economy London: at Bay. MacMillan. The Multinational Spread of Enterprises, New York. Financing Natural Resource Projects, Mimeo, (1986), Fon t ai neb 1 eau Wilson, Sovereignty (1971), . (1982), Lind (Ed.), , New York. Risk Measurement of Public Projects, I R.C. Discounting for Time and Risk in Energy Policy, Washington DC, 205-249. 991 in 032^^ Date ^£Q iy m DuT%f/|/^ Lib-26-67 3 TD6D DDM Q'^B MSO