Document 11072039

advertisement

ruutAincj

<?

or

TlC^

tID28

.M414

ALFRED

P.

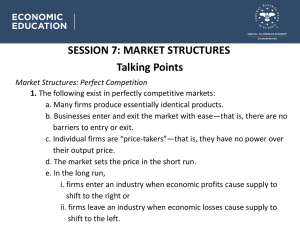

WORKING PAPER

SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT

/,

QUOTAS AND THE STABILITY OF IMPLICIT COLLUSION

by

Julio J. Rotemberg

and Garth Saloner"

WP#1 778-86

May 1986

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

50 MEMORIAL DRIVE

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 02139

'"quotas and the stability of

implicit collusion

by

Julio J. Rotemberg

and Garth Saloner-WP#1 778-86

May 1986

"Sloan School of Management and Department of Economics, M.l.T.

respectively.

We would like to thank Robert Gibbons and Paul

Krugman for helpful comments and the National Science Foundation

(grants SES-8209266 and IST-8510162 respectively) for financial

support

:?

-^o,

^-

i

AUB 2 7

Ills'"

1986

|

!o

I

Introduction

This paper shows that the imposition of an import quota by one country can

protection can reduce the

lead to increased international competitiveness:

price in the country that imposes the quota, the foreign country, or both.

somewhat paradoxical result emerges from a model

of implicit collusion

will

ensue

if

collusion that can be sustained

Our

strategic variables.

variables

Since a quota reduces the

punish a deviating domestic firm, the amount

ability of the foreign firms to

We study both the case

The more powerful the

any firm deviates.

threat, the more collusion that can be sustained.

In such

by the threat that

a setting the firms in an industry sustain collusive prices

more competitive pricing

.

in

is

This

of

correspondingly diminished.

which sales and the case

results are strongest

when

which prices are the

in

prices are the strategic

quotas always make monopolization of the domestic market more

:

difficult in that case.

This

is

in

sharp contrast

to the results in static

imperfect competition models in which quotas tend to make

domestic firm to act as a monopolist at home.

It

is

it

easier for the

also different from the

impact of tariffs which, in a dynamic setting like the one studied here, do not

necessarily make

Whether

it

tariffs

more

difficult for the firms to sustain collusive

make coDusion more

difficult to sustain or not

outcomes.

depends on

the severity of the punishments that the firms can reasonably be expected to

inflict

on their cheating rivals.

The maximal punishments

developed by Abreu (1982) involve an outcome

This

in

.

can,

willing to tolerate the ensuing losses,

it

if

it

makes

result,

is

it

is

which the domestic firm earns

because even with a very large

zero profits

of the style

tariff,

the foreign firm

charge a price so low that

impossible for the domestic firm to earn profits at home.

tariffs

do not affect the abUity of the duopoly

to maintain

As a

monopolistic outcomes.

There the maximum punishment the foreign firm

Contrast this with a quota.

can

still

inflict

on the domestic firm

is

to sell its entire quota.

Thus

yields positive profits for the domestic firm.

firm faces a lower punishment,

monopolistic outcome.

fact that,

it

as pointed out

has a larger incentive to deviate from the

by Davidson (1984), trade restrictions

country to

share of the domestic market.

Thus the domestic

favor and thereby giving

also

make

more

it

In this case of maximal punishments,

firm's incentive to abide

to lose

if

it

deviates.

therefore, our results have the

In his classic paper he

showed that a single domestic producer who faced

a competitive foreign

a single domestic

producer and

than with a quota.

tariff

by

by altering the market

opposite implication of those of Bhagwati (1965).

would act more competitively with a

it

the domestic country have a larger

let

the collusive scheme can at least be partiaUy restored

its

since the domestic

This general intuition must be qualified somewhat by the

less costly to the foreign

shares in

This generally

a single foreign

market

When we consider

producer, the opposite result

emerges.

If

the punishments are not as grim as this, but instead involve reverting

to the equilibrium

from the one-shot game

in

each period, then large tariffs

(which are anologous to small quotas) make collusion more difficult

In that case,

to sustain.

then, the consequences of tariffs and quotas are similar.

As mentioned previously, our results are strongest for the case

prices are the strategic variables.

When

quantities are the strategic variables

we

we analyze the case

in

in

which

which

find that only small quotas break the

discipline of the oligopoly while large quotas,

if

anything, strengthen the

incentives to go along with the monopolistic outcome.

Thus our

case parallel closely those of Davidson (1984) for tariffs.

results for this

He uses quantities

as the strategic variables in a model very similar to ours and shows that small

promote collusion, while the opposite

tariffs

true for large tariffs.

is

After considering the effects on monopolization in the country that imposes

the quota

we study the foreign repercussions

we used

that the arguments

We

of quotas.

notice immediately

show that more competition emerges

to

country

in the

that imposes the quota also imply that quotas lead to increased competition

abroad

the the domestic firm

if

is

We model the capacity

capacity constrained.

constraint in a simple way, assuming that the firm can produce at constant

marginal cost up to some

quota

is

limit

and cannot exceed that

imposed when the domestic firm

the monopoly output

is

to

a

capacity constrained in this way.

If

be sold in the domestic market, the presence of a

quota requires that the domestic firm

a limited capacity to

is

Suppose that

limit.

sell

more

at

supply the foreign market.

home.

Therefore,

it

has only

In that case its capacity

constraint has the same effect abroad as the quota does on the imports of the

foreign firm.

in the

Thus, for the reasons discussed above, more competition results

foreign market.

It

is

possible for quotas to lead to increased competition abroad even in

the absence of capacity constraints, however.

levels of

demand fluctuate over

the two markets.

In that case,

time

and

in either

Suppose, for example, that the

are not perfectly correlated across

market taken alone,

unable to sustain the monopoly level of prices in

and Saloner (1906), when demand

is

outweigh the punishment which

meted out

is

demand.

states.

sufficiently high,

As Bernheim and Whinston (1986) show,

sustain higher profits

all

in later,

in

the firms

As

in

Rotemberg

(which

is

may

the incentive to cheat

"more normal", periods.

such settings the firms can

when they share two markets with imperfectly

In the simplest case,

may be

also the one that

correlated

we study), the

markets are of equal size and have perfectly negatively correlated demand.

In

that case the two markets taken together are perfectly stable over time

and

hence, since the firms' incentive to cheat doesn't fluctuate over time, they may

be able to sustain monopoly profits each period.

Imposing a quota on one of the

markets, however, means that the firms lose the countervailing force that

smooths the incentive to cheat when demand

Instead, the foreign market

is

high

in the

foreign market.

transformed into a market with fluctuating demand

is

and monopoly profits may no longer be sustainable there.

Thus the

market or

imposition of a quota can increase competition in the foreign

domestic market.

in the

The natural question

is

whether the separate

analyses discussed above can be combined to show that the imposition of a quota

can contemporaneously increase competition in both the domestic and foreign

markets.

We show

The presence

that this

is

indeed the case.

of implicit collusion is not the only reason

result in increased competition in both markets.

model developed

in Dixit

why quotas may

Indeed we demonstrate that the

and Kyle (1985) can be modified

to

show that potential

entry can have the same effect.

The paper

is

organized as follows:

We show that quotas can increase

competition at home with prices as the strategic variables in Section

with quantities as the strategic variables in Section HI.

use the analysis developed

in

increased competition abroad

show that

in

is

if

the domestic firm

demand

In Section IV,

is

we

in

We

capacity constrained.

that this can occur even

not capacity constrained in Section V.

show that increased competition can result

market.

and

these sections to show that quotas can lead to

the presence of fluctuating

the domestic firm

II

In Section VI

when

we

both the domestic and the foreign

Section VII concludes the paper with a discussion of the effect of

potential entry.

II

Quotas and price competition

at

home

We consider an

There are two countries, domestic and foreign.

oligopolistic industry with one domestic

the simplest case

restriction

in

is

we assume

both countries.

Marginal cost

is

buy the good

so that consumers can only

slightly contradictory assumption

P

=

a

where P

is

constant and equal to c

is

own country

in their

it

made mainly

2

.

for tractability

Thus

the foreign

Yet, and this

does at home.

by the two firms are viewed as perfect substitutes

is

This

sales abroad.

However, the markets are segmented

firm can charge a different price abroad than

Demand

start with

Foreign firms do not face any transportation costs from

shipping the good to the domestic country.

sold

makes no

that the domestic firm

relaxed in Section IV.

To

and one foreign firm.

,

the goods

the domestic market.

in

given by:

-

bQ

(1)

the industry price and

Q

is

the

sum

of the

amounts sold by the

domestic and foreign firms.

In this section price

is

This means that

if

one

supplies the entire market.

If

the strategic variable.

firm quotes a price lower than the other,

it

two firms quote the same price they share the market

assumptions about the way

gets half the market.

feasible

in

which this sharing

The second

is

the presence of quotas the foreign firm

case.

Thus the

There are two possible

done.

The

first is that

that any possible market division

and that market shares are also

the market.

is

.

implicitly

agreed upon.

may be forced

the

to

each

is

However,

in

have less than half of

latter assumption is the only one that

makes sense

in this

We

start

by analyzing equilibrium under free trade.

This equilibrium

3

the standard duopoly equilibrium in a repeated setting.

is

We assume that the

firms try to sustain the monopoly price (a + c)/2 and that they each serve half

the market.

If

4

Then,

2

if

either firm deviates,

market so that

neither firm deviates, each earns (a-c) /4b per period.

it

undercuts the price slightly and captures the entire

However, after

earns twice this amount.

it

a deviation the firms

are assumed to revert forever to the noncooperative equilibrium for the

corresponding one-period game which has a price equal

This punishment which gives each firm profits of zero

possible punishment that can be conceived

industry

5

It

.

is

if

to the

is

marginal cost

c.

also the strongest

the firms are free to leave the

then impossible to make them earn negative profits.

With this punishment, each firm will be deterred from deviating as long as:

(a-c)^/4b < 6(a-c)^/4b(l-6)

where the RHS

of this equation represents the future profits that are given

by cheating and

long as

6

6

is

the rate at which future profits are discounted.

equals at least 1/2, the monopoly price

We now consider the

effect of a quota.

allowed to import be E(a-c)/b so that

sold

Similarly,

of

if

e

is

1/2,

it

demanded

can

is

sell

So as

sustainable.

Let the amount the foreign firm

is

scaled by the amount that would be

A quota where

under perfect competition.

firm to supply the amount

it

is

up

e

is

1

would allow the foreign

at a price equal to

the amount

demanded

marginal cost.

at the

monopoly price

(a+c)/2, and so on.

Notice as an aside that any quota which

is

binding

equilibrium, i.e. which reduces the amount Imported,

measures

of domestic welfare.

This

is

at the original

raises the standard

so because, even

if

the price remains at

(a+c)/2, the domestic firm having higher sales,

now earns higher

profits.

c

Domestic welfare

is

only increased further

the national identity of firms

if

the price actually falls

however, we focus mainly

a slippery concept,

is

Since

.

on the competition-enhancing affects of quotas.

We begin studying the equilibrium with quotas by analyzing the

punishments for deviating from the

standard practice

(1971),

in

understanding.

implicitly collusive

As

is

models of repeated oligopoly (see for example, Friedman

Rotemberg and Saloner (1986) and Brock and Scheinkman (1986)) we assume

that firms revert to the

Nash equilibrium

in the

deviates from the collusive understanding.

who focuses instead on

While, as

one -shot game

This

if

in contrast to

is

any firm

Abreu (1982)

the maximal feasible punishment for any deviating firm.

we show below, our results are not very sensitive

to

our assumption of

one-shot Nash punishments, there are three reasons why these may be preferable

even when they are lower than the maximal punishments.

the firm can

place

is

sell

of the firm to signal,

to post prices other

signalling

is

if

the owners of

the firm forward, the only equilibrium until the sale takes

the one-shot Nash equilibrium.

managers

First,

7

Second,

it

is

in the interest of the

once punishments begin, that they are unwUling

than those of the one-shot Nash equilibrium.

credible

maximal punishments as

in

If

this

Abreu (1982) become

Q

infeasible.

Third, the one- shot Nash equilibrium

easier to characterize

is

than the maximal punishments.

The

static

one-shot game to which firms revert when they are punishing each

other has no pure strategy equilibrium.

Kreps and Scheinkman (1983) analyze the

mixed strategy equilibrium, and compute the expected profits of the firm with

larger capacity.

They

also exhibit one such

mixed strategy equilibrium (for

which they compute the entire distribution of prices)

show that

this equilibrium is the

.

It

is

straightforward to

unique mixed strategy equilibrium and thus

to

also

compute the expected profits

We now

list

of the foreign firm at this equilibrium.

The arguments behind

the salient features of this equilibrium.

these assertions are contained in the appendix:

The highest price charged by both firms

(i)

The lowest price charged

(ii)

(a+c)/2

=

and

(iii)

e)

2

it

is

[a+c-E (a-c) ]/2.

is

is

(a-c)(2E-E^)^^^/2

-

(2)

charged by both firms with probability zero

In equilibrium,

the domestic firm has expected profits of (a-c)

/4b per period while those of the foreign firm equal

e

2

(1-

(o-c) (a-c)/b.

Notice that this static equilibrium has the features of the differentiated

products model of Krishna (1986).

A higher quota

highest and lowest price charged.

Kreps and Scheinkman (1984) show that the

entire distribution of prices

is

(a

stochastically dominated

higher

e)

lowers both the

by that with

a lower

quota.

There

comment.

c)

2

is

one more feature of this punishment equilibrium that deserves

At this equilibrium the domestic firm earns a present value of (a-

2

What must be noted

(1-e) /4b(l-6).

is

that the domestic firm can never earn

less than this present discounted value of profits at

The reason

one involving maximal punishments.

firm can gviarantee for itself that

is

for this

2

it

is

that the domestic

2

wUl earn (a-c) (1-e) /4b per period by

posting a price equal to [a + c-E (a-c) ]/2b.

the domestic firm

any equUibrum; even the

This

what gives quotas their

limit

on the punishability of

ability to

break the monopoly

price

With the value of the punishments in hand we now turn to the analysis of

the repeated game.

The price preferred by the domestic

(a + c)/2 while the foreign firm,

higher price.

which

is

firm continues to be

subject to a quota, naturally prefers a

Yet we concentrate on the question of whether the duopoly can

We do

sustain the "monopoly" price of (a + c)/2.

First,

this for two related reasons.

higher prices are more difficult to sustain so that

sustain (a+c)/2 they cannot sustain any higher price.

whether the introduction

in

if

the firms cannot

Second, we are interested

of a quota lowers equilibrium prices

from their free

trade level of (a+c)/2.

The

firm

is

sustainability of the price (a + c)/2

expected to seU

allowed to

sell its

have no incentive

deviate since

is

expected

it

at this price.

entire quota,

to deviate.

earns more

foreign firm

the foreign firm

In this case,

game.

Similarly,

2

Instead,

/2b.

if

to sell

y(a-c)/b (0<y<l)

1/2,

in

which case

it

sells its entire

1/2,

in

which case

it

sells

Consider

2

c)

/2b.

(£

first the

It will

which the

in the collusive

arrangement.

its profits

it

in

which

t

is

-

quota, and the case in which

it

By

+

E

-

6e(2e

-

2

E

)^/2

exceeds

deviating, the foreign firm earns E(a-

e(2e

-

E^)^/^]/2(l-6)

(3)

or:

V >

sells

(a-c)/2b.

former case.

E

are y(a-

smaller than or equal to

thus choose to deviate unless:

y)/2 < 6[p

-

in

entire quota at a price essentially identical to

its

We analyze separately the case

(a+c)/2.

the foreign firm

deviates by undercutting the price slightly,

it

demand or

either total

if

the domestic firm never deviates but the foreign

Then, by going along with the collusive arrangement,

c)

is

the domestic firm will always

we consider the intermediate case

So,

supposed

is

for instance,

E(a-c)/b, at this price the foreign firm will

in the static

to sell nothing,

firm always deviates.

If,

depends on the amount the foreign

1

.

(4)

11

Note that for small

e,

must essentially equal

y

that the price will roughly equal (a+c)/2

punished

9

Thus

at the

is

Note also that the higher

is

the firms' discount factor,

it

is

monopoly price

On

that price.

is

being

sell essentially its

y/2

if

it

goes along

cheats

it

sells

it

can

2

the other hand

-

If it

while

of (a + c)/2,

Thus the domestic

y/2 < 6[E/2

allowed to

knows

firm

6,

entire

the less

willing to sell without cheating.

consider the domestic firm.

cheating.

goes along or

it

the foreign firm

Now

it

deviates unless

.

capacity.

whether

The foreign

e.

sell

(a-c)(l/2

-

vi)/b

(a-c)/2b at

2

earns only (a-c) (1-e) /4b per period after

it

firm

is

deterred from price-undercutting

if:

e^/4]/(l-6)

-

or:

y < 6e

-

6e^/2.

(5)

Equation (5), which

y

must be relatively small

since higher levels of y

is

if

valid also

when punishments

the domestic firm

is

to

are maximal,

shows that

be deterred from cheating

make cheating more attractive without increasing

its

cost to the firm.

If

(4)

and

To

sustainable.

(5)

contradict one another the monopoly price

see under what conditions this occurs

is

not

we combine the conditions

and obtain:

e{

1

-

6

-

6[(2e

-

e^)^'^^

-

E/2]l < 0.

(6)

For

small

E

enough we can neglect the term

second order) and the condition

clearly violated.

is

saw that the foreign firm must be allowed

But the domestic firm always requires that

strictly smaller than

e

for y equal to

;

in

e

it

square brackets (which

When

e

small

is

is of

enough we

to sell essentially its entire quota.

y

be smaller than

6e

which

is

has too strong an incentive to

undercut the monopoly price

For

brackets

increasing in

is

up

e

entire quota

when

.62 for (6)

cheats

to

the term in brackets

1

z

until

it

cheats

is

square

only

this the foreign firm cannot sell its

e

,

6

must exceed about

y)/2 < 6[y

-

E

exceeds 1/2 so that when the foreign firm

e

Then the foreign

earns (a-c) /4b.

-

Yet this analysis

in

be satisfied.

consider the case in which

(1/2

The term

positive.

For this maximal applicable

.

2

it

is

reaches .553.

e

beyond

to 1/2 since

relevant for

Now

and

between

E

+

e(2e

-

firm will cheat unless:

e^)^''^]/2(1-6)

or:

y > (l-6)/2

+

-

6e

6£(2e

-

t'^)^^^

(7)

.

which must now be satisfied together with

(5)

for monopolization to be feasible.

So we substitute (7) (holding with equality) in (5) and obtain:

(l-6)/2 < 6e(2£

For

demanded

E

-

£^)^/^

equal one, that

is

-

6e^/2.

when

at the competitive price,

(8)

the foreign firm can sell the entire quantity

(8)

requires that

6

exceed 1/2 as

it

did

13

under free trade.

Since the

(and thus of

of 6/(1-6)

6)

RHS

of (8) is strictly increasing in t,

required to make (8) hold,

the level

when

falls strictly

e

rises.

To summarize

the results of this section, more restrictive quotas (starting

quota which allows the foreign firm to

at a

sell

demanded

the entire amount

at

the competitive price) monotonically reduce the ability to monopolize the

Note that, for a given

market.

domestic market

is

6,

the quota that gives the minimum price in the

one which satisfies

strictly smaller than the

When these equations hold with

with equality.

For lower values of

sustainable.

equality, monopoly

However,

the price falls.

t,

(or (8))

(6)

is

just

the quota

if

is

reduced significantly more, the price starts rising again as the prices charged

even

In the

one-shot game rise.

For

equal to zero, the monopoly price

t

is

reestablished.

It

must be pointed out again that the increased competition brought about

by quotas

is

not sensitive to the use of one-shot Nash punishments.

instance even

deviations by the foreign firm lead this firm to earn zero

if

profits from then on (which for low

e

is

a

much harsher punishment than

maximal punishment) the foreign firm wUl require that

so as to refrain from deviating.

1/2

and any positive

This

is

y

briefly

compare the results

analyzing tariffs in a similar setting.

of the foreign firm are higher,

domestic firm.

6

equal to

e.

in this setting is in

direct contrast to the conclusions of the static analysis reported

We now

the

equal at least (1-6)e

inconsistent with (5) for

The increased competition brought about by quotas

(1985).

For

by the

The repeated game

in

A

to those

by Krishna

one would obtain when

tariff simply implies that the costs

tariff rate,

than the costs of the

which the two firms have different costs

has been analyzed by Bernheim and Whinston (1986), who consider optimal

punishments

firms

in

the style of

Abreu (1982).

Then, both the domestic and foreign

earn zero profits when they are being punished

still

.

This means that

the incentives to participate in the implicit agreement that requires that the

price (a + c)/2 be charged, do not change as a result of the tariff.

Moreover,

Bernheim and Whinston (1986) show that the equilibrium that Involves the highest

profits for the duopoly as a whole

now has

a price higher than (a + c)/2.

This

occurs because the profit maximizing price from the point of view of the foreign

firm

is

now higher.

So a

tariff

has the potential for increasing the domestic

price above the monopoly price.

Thus,

in the case of

maximal punishments the classic results of Bhagwati

(1965) about competition between a foreign and a domestic firm, are precisely

reversed.

A

quota, because

punished effectively, makes

consequence.

it

makes

it

impossible for the domestic firm to be

difficult to collude,

while a tariff has no such

This raises the intriguing possibility that this

governments seem

However,

it

it

to prefer quantitative restrictions to tariffs

is

the reason

12

must be pointed out that the robustness of the monopoly outcome

with respect to a tariff

is

sensitive to the use of maximal punishments.

If

instead, reversions to the Bertrand outcome are used, a tariff which raises the

foreign firm's costs barely below the monopoly price of (a+c)/2 makes the

monopoly price unsustainable.

The reason

for this

is

that to maintain this

price the domestic firm must give a sizeable fraction of the market (1-6) to the

foreign firm.

Thus

if

the foreign firm's costs are near (a+c)/2 the domestic

firm will actually earn more during the period of punishment (when

price barely below the foreign firm's costs) than

when

it

it

charges a

goes along with the

monopoly price

The

results of this section are sufficiently striking that they deserve to

be qualified somewhat further.

The analysis hinges

critically

on the presence

15

Since this means that only the foreign firm can

of only one domestic firm.

punish the domestic firm,

of a quota.

punishment

this

ability is curtailed in the

presence

there were more domestic firms in the market, they could

If

revert to a price of

c

if

any

of

all

them deviated and thus keep the oligopoly

the monopoly outcome even in the presence of a quota.

On

at

the other hand,

if

the

domestic firms are capable of concerted cheating, the approximation considered

only one domestic firm

in this section of

Ill

may be

a

good one.

Quotas and quantity competition at home

In this section

we assume

This has two consequences.

competitor

amount.

when

First,

deviates.

neither firm eliminates the sales of

These are maintained

in quantities,

which

is

prices are the strategic variables.

The

its

at the implicitly colluding

Second, punishments are characterized by reversion to the single period

Nash equilibrium

when

it

that quantities are the strategic variables.

a

much milder form

of

punishment than

13

results of this section are directly comparable to Davidson's (1984)

analysis of tariffs, in which he also assumes that quantities are the strategic

variables.

collusion

to import

We show

that the result that quotas lead to less sustainabUity of

now only holds

very

little.

for

very restrictive quotas that allow the foreign firm

For larger quotas, we find that collusion

anything, enhanced by the quota.

Thus our

Davidson's (1984) since he shows that

is,

if

results here are similar to

small tariffs (which correspond to large

quotas) enhance collusion while large tariffs do the opposite.

Again, the firms are assumed to be able to monopolize the domestic market

in the

absence of quotas.

2

earns (a-c) /8b.

If

By going along

with selling (a-c)/4b each, each firm

either firm were to deviate

it

would choose

to sell 3(a-

2

c)/8b which would give

profits of 9(a-c) /64b in the period of the deviation.

it

From then on, the firms would revert

would

will

to

Cournot-Nash equilibrium so that each

2

(a-c)/3b and earn profits of (a-c) /9b per period.

sell

be deterred from cheating

[9/64

-

Now

6

-

1/9] (a-c)^/b(l-6)

So suppose that

level of sales,

it

is

to the

If

e

is

above 3/8, so that the quota

monopolizing level of output,

has no effect.

it

lower than this level but higher than the Nash equilibrium

that

i.e.

,

exceed 9/17.

consider a quota of E(a-c)/b.

exceeds the best response

each firm

if:

l/8](a-c)^/b < 6[l/8

which requires only that

So,

z

is

between 3/8 and

1/3.

Then

the quota does not

affect the foreign firm's ability to punish the domestic firm from deviating

(since each firm produces (a-c)/3b

in

makes the foreign firm's own deviation

cannot now exceed E(a-c)/b.

Cournot-Nash equilibrium.

it

done

in the

So such a quota has no effect when the firms can

absence of a quota.

is

For suppose that

selling (a-c) /4b,

constrained,

somewhat lower.

since

it

6

is

it

when

it

now earns

will still not

This means that

With

z

not only wUling to go along with

is

less

when

it

deviates than

may be possible

if

In essence,

it

its

does

if

it

sales are

to sustain the

output by having the foreign firm produce less than half of the

domestic firm produce more than half.

may

just below 9/17 so that

be induced to cheat even

it

actually

this cannot be

not sustainable in the absence of a quota.

between 3/8 and 1/3 the foreign firm

isn't

Furthermore,

possible to sustain this monopolistic outcome even

the collusive output

it

less profitable since this deviation

sustain the monopolistic outcome without a quota.

make

However,

monopoly

total,

and the

the "excess" unwillingness to

cheat on the part of the foreign firm can be used to free up the constraint on

17

the domestic firm.

Thus

for a quota to promote competition

equilibrium (a-c)/3b,

detail.

We

t

must be below the Nash

it

We now analyze such

must be less than 1/3.

on the part of the foreign

first look for the lowest level of sales

firm which makes

willing to go along with an equilibrium

it

Then we analyze whether

(a+c)/2.

Suppose that the foreign firm

and that the firms attempt

the domestic firm

by the foreign

this price given these sales

p(a-c)/b in equilibrium

to sell

of output.

derive the minimum level of y for which the foreign firm

By cooperating

deviate.

2

sells Its

It

output

The domestic firm

earns (a-c) y/2b.

requirement that

deviates

sells

-

We

y)/b.

This

y.

is

We now

not want to

(a + c)/2 so that

at a price of

it

monopoly output

show below that the

be smaller than 1/3 Implies that when the foreign firm

z

E(a-c)/b.

Thus when

it

deviates

2

it

Note that the profits to the foreign firm when

p)/b.

in

it

will

sells that portion of the

not sold by the foreign firm, or (a-c) (1/2

is

willing to go along with

is

monopoly level

to sustain the

whose price

firm.

supposed

is

a quota in

because the higher

is

y the

earns (a-c) e(1/2

it

-

+

e

deviates are increasing

lower are the domestic firm's sales

when they both go along with the proposed equilibrium output.

After

game.

its

deviation the market reverts to the equilibrium in the one-shot

Since the quota

is

less than the

Nash equilibrium value

foreign firm sells E(a-c)/b while the domestic firm sells

this level of output,

E)/2b.

Hence the foreign firm

(a-c)^{E[l/2

i.e.

or (a-c) (l-E)/2b.

if:

+

y

-

e]

-

will

its

Thus the foreign

-

e

the

best response to

2

firm earns (a-c) e(1-

be deterred from deviating

y/2!/b < 6(a-c)^[y

of (a-c) /3b,

if:

(1-e) ]/2b(l-6)

y >

E

-

6e^/[1

2e(1-6)]^^.

-

Note that for values of

for this

is

when

that

near zero, the foreign firm

e

the implicit agreement allows

(9)

is

deviating unless

it

that for sufficiently small

is

already selling

all

as

allowed to

is

that

The reason

price does not differ appreciably from

small,

Then

(a+c)/2, even during the punishment phase.

much

deviate unless

to sell nearly its entire quota.

it

the quota

firm's interest to sell as

will

it

can and

it

always

is

in the

foreign

cannot be deterred from

essentiaUy

sell

it

its

This means

entire quota.

e

the foreign firm has no punishment power since

it

is

allowed to bring in.

Given

surprising that we establish next that for sufficiently small

this,

e,

it

is

it

not

the equilibrium

cannot involve the monopolization of the domestic market.

Suppose that the

Consider the domestic firm's incentive to deviate.

foreign firm

best response to this,

c)

2

(a-c) (l-y)/2b,

2

(l-y) /4b in the period in which

would

sell

The domestic firm would

selling (a-c)vi/b as above.

is

it

if

deviated.

it

It

would then earn

From then on the foreign firm

deviated.

2

2

(1-e) /4b per period.

So the domestic firm would be deterred from deviating only

-

v)^/4

-

(1/4

-

increase

is

y,

easy to see that

when

u falls,

as long as y

is

if:

p/2) <

6[l/4

It is

(a-

(a-c)E/b so that, by an argument similar to that above, the domestic

firm would earn (a-c)

(1

sell its

-

y/2

-

(1

-

E)^/4]/(l-6).

in spite of the fact that profits

the inequality in (10)

smaller than 6/(1-6)

is

more

(which

is

(10)

from deviating

likely to hold the smaller

true by assumption).

The

19

reason for this

Is

that the principal effect of a decrease in y

that the

is

domestic firm earns more by going along with the collusive agreement.

make the domestic firm as

firm sell only as

much

as

willing to go along as possible

required to make

is

(9)

we

Thus

the foreign

let

hold with equality.

Substituting this expression for y in (10), multiplying by (1-6) 1-2e (1-6)

[

collecting terms,

E^(l-26^)

-

we divide

E^(l-6)[4(l-6^)

+

+

by

e

this expression

2

by

(after dividing

(11)

range of

t.

and

26]

e'^(1-6)[4(1-6)

obtain (1-26 )<0, which requires

of

2

]

the inequality (10) becomes:

+

If

to

2

e

This means that

6

46(1-6)

2

+

6^] < 0.

and take the

limit as e

if

6

exceeds .71

it

is

goes to zero we

Furthermore, the LHS

smaller than about .71.

decreases monotonically with

)

(11)

e

in the

relevant

always possible to sustain

the monopoly price.

If,

instead,

6

between 9/17 and

is

.71,

the monopolistic outcome

sustainable with free trade but not with a sufficiently small quota.

is

In this

case of linear demand, however, the quota must be very small for this result to

hold.

If

we take the

smallest discount factor consistent with collusion

under

free trade (9/17), one can demonstrate numerically that the monopolistic outcome

is

not sustainable for

e

equal to .01 but

These are such low values

of

e

is

sustainable for

e

equal to .015.

that even the noncooperative solution looks

essentially identical to the monopolistic solution.

IV Quotas and competition abroad: Constant demand

We now turn

to the implications of the existence of a

quota

at

home for

competition abroad.

Sections

and

II

to

III

we adapt the arguments presented

In this section

in

argue that under certain circumstances they can be

interpreted as providing conditions under which competition increases abroad.

We assume that the domestic and foreign markets are

demand curves are given by

If

(1).

both firms have infinite capacity, there

a monopolistic equilibrium in which (a + c)/2

as

6

identical so that their

is

charged

in

both markets as long

equals at least 1/2 when prices are the strategic variables and

least 9/17

when

becomes

So marginal cost equals

infinite.

in

is

equals at

that the domestic firm actually has limited capacity given

If

k equals

c

for instance,

2,

that this capacity

is

by

untU the firm produces k(a-c)/b and then

the domestic firm can supply the

The

quantity demanded at the competitive price in both markets.

section

6

quantities are strategic variables.

Now assume

k(a-c)/b.

is

idea of this

sufficient to maintain the monopolistic outcome

both countries with free trade.

However, with

a quota that forbids all

imports into the domestic country, the domestic firm must devote a larger

fraction of its capacity to producing for the protected domestic market.

then effectively has a very small capacity for selling abroad.

It

This has the

same effect abroad as would a quota imposed by the foreign country.

We

is

first treat the case in

which prices are the strategic variables.

equal to 1/2 (the benchmark case) and k

is

less than 2,

If

6

the two firms cannot

maintain the monopolistic outcome in both markets even in the absence of a

quota.

This results because the domestic firm does not have sufficient

punishment power

outcome can

to

at best

keep the foreign firm from cheating.

be sustained for values of

6

Thus the monopoly

that are greater than that

required to sustain monopoly under free trade without capacity constraints.

We consider how large the

"critical" value of

6

must be for different

values of k. Note first that k must be at least equal to 1/2 for the problem to

21

be interesting since otherwise the domestic country

own market when

its

suppose that k

is

(the world market

value of

6

that market

6

Now consider

is

6

about

is

about

.

.65.

If

the effect of a quota.

important to notice

is

is

sustainable in the world as a

instead k

at

This

is

is

left

over to

that the domestic firm

is

firm sells (a-c)/2b at

the foreign country.

sell in

is

it

is

never willing

punishing the foreign

selling

it

abroad

This means that the domestic firm

sold at home.

e

we can use

(6)

6

that sustains the monopoly outcome abroad.

value of

6

strictly below

to a value of

is

.65 in the

is

Letting k-1/2 be

minimum

For k barely above 1/2 no

sufficient to maintain that outcome (in contrast

absence of a quota).

For k equal to

1,

a value of

.65

required when only .62 was required under free trade.

We now turn

to the case in

which quantities are the strategic variables.

Hence

Here the monopoly outcome only broke down for tiny quotas.

domestic firm has a capacity of (1/2 +e) where

e

is

negligible,

outcome can be maintained with free trade as long as

other hand, once the domestic market

firm

6

less than

(or (8) for k bigger than 1) to discover the

value of

1

if

effectively

is

capacity constrained abroad with a capacity of (k-1/2) (a-c)/b.

denoted by

to sell

so because the marginal revenue from selling a unit

home always exceeds the marginal revenue from

(a-c)/2b

equal to one, the

is

The domestic

more that (k-1/2) (a-c)/b units abroad, even when

firm for deviating.

equal to k/2

e

62

home and has (k-1/2) (a-c)/b units

What

with

equivalent to twice the domestic market) to obtain the

is

for which the monopoly outcome

value of

critical

(6)

in

So first

to foreign firms.

Then we can use

barely above 1/2.

This value of

whole.

becomes closed

unable to meet demand

is

is

is

willing to sell at most

e

is

abroad.

6

if

the

the monopoly

exceeds 9/17.

On

the

closed to the foreign firm, the domestic

This means that for

e

small

below .71, the monopoly outcome won't be sustainable abroad.

enough

if

V Quotas and

competition abroad: Fluctuating

demand

This section considers a somewhat different model

in the

country tends to increase competition

collusion

is

The

other country.

idea

in

one market, they are small

In this setting,

one

that

is

in the

other market and

the overall incentive to cheat (taking the two

markets together) are fairly constant over time.

If

one looks at either market

Then

separately, however, the incentive to cheat fluctuates over time.

in

in

maintained under free trade only because whenever the net benefits

from cheating are big

viceversa.

which a quota

in

if,

as

Rotemberg and Saloner (1986), future punishments are largely independent

the current period's incentive to cheat, then those punishments

insufficient to deter cheating

high.

It

if

the current incentive to cheat

may be

is

particularly

thus becomes more difficult to prevent them from cheating.

imposition of a quota has the effect of separating the two markets,

makes

implicit collusion

Our

specific model

more

of

it

Since the

thus

difficult.

assumes that demand

is

random

in

both countries, as

Rotemberg and Saloner (1986), and negatively correlated across markets as

Bernheim and Whinston (1986).

To

simplify the analysis

we assume

in

in

that there are

only two states of demand (high and low) whose realizations are independently

distributed over time in any one country and perfectly negatively correlated

across markets.

So when demand

In this section

we assume

is

high

in

one market

it

is

low in the other.

that there are N/2 firms in each market while

do not restrict attention to linear demand curves.

symmetric, the monopoly price in the high state, p

Since the countries are

,

is

the same in both

countries and similarly for the monopoly price in the low state, p

the analysis by ensuring that these two prices p

.

We

start

and p are sustainable with

15

we

23

That

free trade.

is

we consider

a situation in which

all

N

firms sell in both

markets and derive the condition under which no single firm wants to deviate

from charging p

in the

country

in

which demand

is

high and p

in the other.

Prices are again the strategic variable so that any deviation triggers a

permanent reversion

which price equals marginal

to the static equilibrium in

cost.

Let

be the total monopoly profits

IT

those in the market with low demand.

former

in the

market with high demand and

As long as p exceeds marginal

the

cost,

bigger than the latter since the monopoly always has the option of

is

even when demand

charging p

is

A

high.

firm that deviates from the monopoly

outcome undercuts the price charged by the others slightly.

the market in which

deviating

it

demand

gives up both

these profits.

(tt"

it

Thus each

+

TT^)(1

1

< 6/(1

-

is

high and

now and

firm

1/N) < 6(tt"

is

+

in all

In the other.

it

future periods

On

its

thus earns

tt

in

the other hand,

by

It

share (1/N) of

deterred from deviating as long as:

tiVn(1

-

6)

(12)

or:

N

-

-

(13)

6).

We assume that either the number

factor big

enough that

of firms

Is

small

enough or the discount

(12) holds so that with free trade the two

markets can be

completely monopolized.

We now consider what happens when no imports are allowed

country.

This drastic quota has two effects.

fewer (N/2) active firms

in the

First,

it

into the domestic

means that there are

domestic market while N firms continue to

sell

in the

As a

foreign market.

the conditions under which monopoly will be

result,

As

sustainable will be different depending on which market has high demand.

Rotemberg and Saloner (1986) show,

in this setting

sustain collusion

when demand

monopolization

is

possible,

monopolization

is

possible in the high

Consider

/N abroad.

The

Thus

low.

is

always easier to

whether complete

to see

we study the conditions under which such

Any

demand

state.

country when demand

first the foreign

firms try to charge p

It

is

it

high. Suppose that the

is

firm that undercuts this price earns

losses from the ensuing competition are smaller for foreign

countries since domestic countries

may

also lose

any profits they make

So we concentrate on the incentive to deviate of foreign firms.

they lose the expected value of profits

in the future.

If

a foreign firm will deviate

•tt"(1

-

1/N) > 6(tt"

Note that the

of

RHS

+

(it

is

+tt)/2.

if:

ttV2N(1-6).

(14)

of (14) equals half the

RHS

of (12).

The

costs in terms

foregone future profits from deviating are half what they would be

firms had access to both markets.

of (14)

and

is

(14) to hold simultaneously.

in the

it

is

In particular,

if

is

bigger than

it

is

When

it

is

ti

,

the

if

in

the profits

(14)

is

impossible to sustain monopoly abroad

high state of demand so the quota increases competition.

It is

LHS

(12) holds as an equality

just sustainable with free trade) then

(14) holds,

foreign

if

possible for (12)

high and low demand states are different, the inequality

always satisfied.

in the

Yet, insofar as

bigger than half of the LHS of (12) so that

(so that monopolization

home.

at

they deviate

Since demand

independently distributed over time, these expacted profits equal

So,

instead of

it

easy to show that when (12) holds

it

Is

always possible to sustain

25

monopoly abroad

the low state of demand.

in

(12)

ensures that deviations

Yet,

when demand

would prevail

if

is

low,

will

This results from the fact that

when demand

not take place even

constant.

is

expected future losses from deviating exceed those that

demand were expected

This

to stay low forever.

from the fact that even when (14) holds,

it

is

still

possible to sustain

This can be seen as follows;

substantial profits in the high state.

turn results

in

Let the

sustainable price (the highest price that can be charged without inducing any

firm to deviate) in the high state be p

argument analogous

one used

to the

refrain from undercutting p

-

Ti^(l

1/N)

=

6(Tr^

+

s

and the ensuing profits

to derive

(14),

s

it

Then by an

.

a foreign firm will just

if

TiV2N(l-6)

or:

TT^

=

so that

IT

ttV{2(N-1)(1-6)/6

s

equals n

1

when

-

1]}

(15)

(12) holds as

an equality and exceeds

when

it

it

holds

as a strict inequality.

So far, we have shown that under plausible conditions the foreign market

becomes more competitive while

still

retaining substantial profits.

This result

does not hinge on the fact that prices are used as the strategic variables. As

in

Rotemberg and Saloner (1986),

sustain

when demand

is

high.

it

As we showed there, this

quantities are the strategic variables

We now turn

only requires that collusion be difficult to

when demand

is

is

also true

when

linear.

briefly to an analysis of the domestic market.

If

domestic

firms were to deviate from the collusive arrangement they could be punished in

both markets.

oncG.

On

In this case,

the other hand

deviating firms would deviate in both markets at

we have already derived the net benefits from deviating

abroad under the assumption that punishments would only be meted out abroad.

To

complete the analysis we thus look at the net benefits from deviating in the

domestic market alone under the assumption that firms will only be punished in

Then, the

the domestic market for doing so.

the

sum

of these

two net benefits.

Suppose that the domestic market

high, a deviating firm would earn

then lose

It

it

is

instead of

would thus be deterred from deviating

tt"(1

2/N) <

-

The RHS

meted out only

the share

fully monopolized.

share of total expected profits in

its

total net benefits to deviating are

6(tt"

of (16)

in

is

+

its

its

When demand

share (2/N) of

if:

RHS

On

While the punishment

of (12).

one market, the share of each firm

LHS

would

(16)

the same as the

substantially smaller than the

It

.

own market from then on.

ttVn(1-6).

we previously considered.

n

is

in this

the other hand the

of (12)

market

LHS

is

is

double

of (16) is

since deviations are taking place in

one market alone whUe, in addition, the net benefit

is

smaller because there

are fewer firms active in the market and so the firm's share was larger to start

with.

So

(12) is satisfied (even with equality)

if

strict inequality.

In this case

showing that

monopoly

is

This applies to the case

in

then (16)

is

satisfied as a

which demand

is

high at home.

demand

is

low in the foreign market and our previous analysis

there

is

a net loss from deviating there applies.

sustainable in the absence of a quota

home market, then

When demand

it

is

is

when demand

Thus

is

if

high In the

also sustainable with the quota.

low at home the corresponding condition at home has the same

27

RHS

as (16) but an even smaller LHS.

So the net benefits to deviating are

negative here as well.

In

summary, when

holds, monopolization

(12)

is

always possible in the

protected domestic market. Indeed, since protected domestic firms strictly

prefer to go along with monopolization than to deviate when (12) holds as an

we can conclude that protection may make monopolization

equality,

home when

The

was not feasible with free trade.

fact that collusion

potential,

To do

it

in a

richer model, to make monopolization feasible abroad as well.

the market unevenly as

Section

becomes easier for the domestic firms has the

we must allow the

this

II.

feasible at

is

set of firms that

done

charge the lowest price to

split

Bernheim and Whinston (1986) and as we do

in

Bernheim and Whinston (1986) show that the possibility

in

such

of

arbitrary divisions aUows "punishment power" to be shifted from a market in

which there

is

more than enough

monopoly outcomes.

to

one in which there

isn't

enough

to sustain

In our example, the domestic firms can offer the foreign

Domestic firms would

firms a share higher than 1/N of the foreign market.

tolerate this for fear of losing their domestic profits

if

they deviate abroad.

Foreign firms would earn more when they go along with the collusive arrangement

and thus would be

less willing to deviate.

potentially achievable

when demand

does not work, however, when

there

is

N

is

In this

fluctuates relatively

equal to

2

home when

it

little.

deviates abroad.

Then

Its

is

This approach

so that as in Sections

only one firm in the domestic market.

fear retaliation at

way monopolization

II

this firm does not

and

need

incentives to deviate

abroad are the same as those of foreign firms and giving the foreign firm a

disproportionately large market share only increases the domestic firm's

incentive to deviate abroad.

III

to

VI Quotas and Competition in Both Markets

we consider the

In this section

competition at home (as in Sections

Sections IV and V)

fluctuating

possibility that a quota will increase

and

11

The model we use

.

demand model

of Section

as well as abroad (as in

111)

to illustrate this possibility is the

V except

to permit competition to

that,

increase at home, we consider a strictly positive quota.

analysis

we

one firm

in

restrict attention to the case in which

each country, and

6

is

Also,

N equals

to simplify the

so that there

2,

equal to 1/2, so that monopoly

is

is

just

sustainable in both markets with free trade.

Since any firm that deviates in one market will be punished in both, any

deviating firm wUl undercut the implicitly agreed upon price in both countries.

So the incentive to deviate

in

any one country can be thought

of as the

sum

of

the net profits from deviating at home (i.e. the benefits from deviating at home

minus the present value of the losses

home) plus the net profits from

at

deviating abroad.

Suppose that the foreign firm has a share

its

net profits from cheating

when demand

those

when demand

notice

fall

is

that,

as

low are (1-3o/2)it

is

s

is

1

high are (l-3a/2)Ti -otT/2.

net profits from cheating

those

when demand

a of the foreign market.

when demand

is

s

high are (3a/2-l/2)iT -(l-a)Ti /2.

we increase

a,

-ott

/2 while

Similarly the domestic firm's

low are (3a/2-l/2)iT

1

is

s

1

1

s

-(l-a)-!! /2

and

The important thing

to

the foreign firm's net profits from deviating

by the same amount as the domestic profits from deviating increase.

as long as in each state the total net profits from deviating (the

firm's net profits from deviating) are zero,

redistribution of shares that will

Then

there

make both firms

We therefore now concentrate only on the

will

sum

Thus,

of each

always be a

willing to go along.

total incentive to deviate.

In

29

the foreign country this

s

So unless

state.

abroad

is

it

is

equal to

home

at

We can then write the quota

enough

small

Is )/2

-it

1

it

in the

low state and

foreign firm

is

t

is

given by P=a -bQ (where

in state

Suppose that

less than 1/2.

is

as equal to

i

decreased incentive to deviate

is

(a -c)

e

[e (1-6)

+

/2

6e

-

violated which

6z {2t -t

This

(a -c)/b

at the

)^

to maintain

expression

s

1

abroad.

)

in

monopoly

(17) with

i

at

if

the quota

monopoly price the

(4)

the

we can obtain the

]/h

y

one firm's

(17)

home.

replaced by

1

This

6

is

the same as that (6) be

is

equal to 1/2 in Section

in the

is

At least one of these net incentives

i

two markets taken together

given by

when demand

plus the expression in (17) with

II.

domestic market.

in the

consider the net incentive to deviate

we try

where

1)

given by:

is

for the case in which

thus a net incentive to deviate

Now

(tt -tt

we proved

equals either u or

i

Once again by varying

Note that the condition that (17) be positive

by

positive

the other's increased incentive so we can

focus on the total incentive to deviate.

if

is

high

in the

-it

Then we can obtain from

allowed to seU y (a -c)/b.

domestic firm's net profits from deviating.

is

si )/2

the total incentive to deviate

foreign firm's net profits from deviating while from (5)

There

(it

one of the two states.

in

Suppose demand

is

(tt

is

s

(tt

1

-it

)

plus the

high abroad.

It

is

replaced by u when demand

is

positive so that

it

given

is

low

is

impossible to sustain monopoly at home.

Now we consider whether

it

is

possible to have an outcome different from

the monopoly outcome at home such that the net incentive to deviate at home

is

so negative that the monopoly outcome can be maintained abroad even in the high

state.

That this

is

unlikely for small quotas should be apparent since, then.

the static game gives about as

many

profits as the monopoly outcome.

This

suggests that there are no prices between the monopoly price and those that

prevail under static competition for which the costs of reverting to competition

are high.

We now consider

and study the overall profits from deviating

home.

at

a price p at

home

The amount demanded

(a-p)/b and, since the distribution of this demand across firms

this price is

immaterial,

We consider

more formally.

this issue

we

the foreign firm seU

let

sells the difference

e

at

is

(a -c)/b while the domestic firm

between the quantity demanded and the quota.

The domestic

firm's net profits from deviating are then given by:

E^(a'-c)(p-c)/b

-

(p-c)[(a'-p)-E(a^-c)]/b

+

(a'-c)^(l-E V/4b.

The foreign firm gains nothing by cheating but

the static game

e

(a

-c)(p

its

cost from reversion to

is:

-

a]/b

so that the overall benefits from deviating are:

{p-c)(t\a^-c)

whose minimum

is

-

(a^-p))/b

(a^-c)^(l-E^)^/4b

+

reached for a p equal

+

E^a^-c) (o-c)/b

[a +c-£ (a -c)]/2.

There, this

expression equals:

{-E^/2

+

e[1

-

(2e-e^)^^^

+

E^]!(a-c)^/2b

(18)

31

which

is

maximum

negligible for small

e

.

The

cost from deviating at home,

fact that

0,

(18)

small.

is

is

small

means that the

maximum

Yet,

profits in the

high state abroad must satisfy:

(tt^

-

TrV2

-

so that for small

to

*

it

<

impossible to make

is

s

it

equal to

in

which

Tn

it

as would be required

monopolize the foreign market.

VII

.

Conclusions

We have shown

in a variety of

models

implicit collusion is

important that quotas have the potential of increasing competition, not just in

the domestic market, but also abroad.

those obtained

when there

is

These results stand

a single domestic firm

in

sharp contrast

to

and goods from abroad are

supplied competitively (Bhagwati (1965)) as well as those obtained when domestic

and foreign firms act as

The

in a one- shot

game.

intuition underlying our seemingly paradoxical results are not

restricted to quotas.

competition

less viable.

Indeed, any action by the government which makes

when coUusion breaks down more

profitable

Thus Government imposed minimum

makes collusion

itself

price floors could have precisely

the same effect.

One natural question

to

ask

is

whether our results depend

critically

on the

existence of implicit collusion or whether they can also be generated in other

models of strategic interaction.

would be modified

in the

In this conclusion

One particular concern

is

how our

results

presence of entry.

we sketch an argument that shows that quotas

also tend

to increase competition

The

the industry.

by encouraging the entry

we consider

setting

new (domestic) firms

very closely related

is

to that

into

developed

They analyze an industry with an established foreign

and Kyle (1985).

in Dixit

of

firm and a domestic potential entrant.

They show

that

it

possible that

is

if

the domestic country prohibits imports that there will be more competition in

the foreign market.

This occurs because the potential domestic firm may find

unprofitable to enter

if

By protecting

it

in the

it

must compete with the foreign firm

domestic market

(while

market), the domestic government provides

its

fixed costs.

competes

both markets.

in the

foreign

with sufficient revenues to cover

then finds entry attractive, enters, and increases

It

Since the domestic market was monopolized in any event, the

competition abroad.

domestic country

it

it

in

it

is

made better

off since

consumer surplus

is

unaffected and

rents have been shifted towards the domestic country.

This analysis can easUy be extended to include the case of a nonzero

Moreover,

quota.

it

not only does competition increase abroad, but

in that case,

Consider the case where the firms

increases in the domestic country as weU.

compete with outputs as their strategic variables

if

entry occurs.

Suppose

further that the domestic potential entrant will find entry worthwhile

earns

its

K

is

greater than

than the domestic monopoly revenues.

quota which

is

its

Now

domestic Cournot revenues and less

let

the domestic government impose a

such that the domestic firm earns revenues of K when

best-response to the quota.

to enter

it

competitive revenues abroad plus some amount, K, of revenues in the

domestic market, where

its

if

and does

so.

Once

it

In that case the potential entrant

is

it

produces

willing

has entered the firms produce their Cournot

outputs in the foreign market, and in the domestic market the foreign firm

its

quota while the domestic firm

increases in both countries.

sells its

best-response

to that.

sells

Competition

33

The

protect

Dixit

its

and Kyle (1985) insight

domestic firm

above analysis points out,

insulation in its

fvirther

order

in

is

own market

to

is

that the domestic country

encourage

it

to enter.

that the domestic firm

in

may

may have

However, what the

not need complete

which case domestic welfare can be improved even

by allowing some foreign competition.

In contrast to

our analysis

is

this result holds

whether the

a quota or a tariff.

All that is

in Section II,

instrument used by the domestic country

required

is

that the domestic government increase the domestic profits of the

domestic potential entrant to the point where entry

tariff raises the costs of the foreign firm,

is

they make

attractive.

it

Since a

"less aggressive" in

the domestic market which in turn makes that market more attractive to the

potential entrant.

Thus when considerations

to

of implicit coUusion or of potential entry are

important, quotas can lead to greater competitiveness.

APPENDIX

appendix we consider the one- shot game

In this

and

strategic variables

which one

in

made

establish the claims

s =

[a

+

namely that:

in the text,

The lowest price charged

(ii)

(a+c)/2

=

and

(Hi)

-

is:

this lowest price is

charged by both firms with probability zero

the foreign firm earns e(o-c) (a-c)/b.

In equilibrium,

of these in turn:

The highest price charged by both firms

the domestic firm,

it

will

never choose

to

charges

its

highest price,

But the price that maximizes

which

(11)

is

its

than

Hence the domestic firm knows that

be undercut with probability one.

when

it

is

undercut for sure

is

s,

therefore the highest price charged by the domestic firm.

The lowest price charged

is

if

it

e

-

(a-c) (2e-e2)1/2/2

and

First,

it

.

(o)

This price

cannot be the case

its

In

which the domestic firm would be willing

o

(i.e.

has a number of interesting

in

an equilibrium that the foreign

firm always charges a price strictly above a.

would always make more than

(iii)

(o-c) (a-c)/b.

could thereby be sure to capture the entire market

undercut the foreign firm)

properties.

(a+c)/2