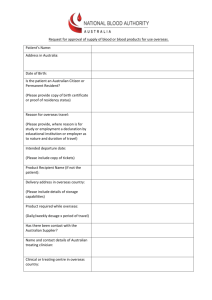

Document 11072037

advertisement