Document 11070349

advertisement

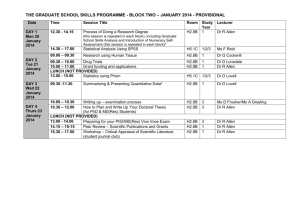

'^ o/ Tt^"^ rrt/- —B' ALFRED P. WORKING PAPER SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT Project Team Aging: Thomas Allen Ralph Katz J.J. Grady Neil Slavin A Failure to Replicate November 1987 CT/1963-87 MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 50 MEMORIAL DRIVE CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 02139 Project Team Aging: Thomas Allen Ralph Katz J.J. Grady :;eil Slavin A Failure to Replicate November 1987 WP/1963-87 FFB 5 1988 INTRODUCTION The phenomenon years by to relate a "group aging" of number is one that has been reported over the Shepard of separate investigators. group performance to the mean tenure (1956) was the group members. of found that performance increased with increasing average tenure up about 16 Pelz and Andrews (1976) found performance reached its maximum yet another study, years, just as Pelz and & Alien, 1982) Smitfi at a In mean tenure (1970) showed Andrews found. reported, for 50 projects a Finally, in a their study, of four years (Figure performance peak at four the present authors (Katz U.S. chemical company, clear curvilinear relationship with performance again at to similar curvilinear a relationship between mean tenure and performance. In He months, but decayed as group membership remained stable over longer periods. 1). first reaching a a maximum about the three to four year point for mean project team tenure and decaying significantly thereafter (Figure 2). There is therefore substantia! evidence for the existence of the reported curvilinear relationship between mean tenure and project team performance. The research has been conducted by a number of independent investigators, who have examined groups and project teams number very different industrial settings across a time. Katz and Allen (1982), after reporting their observations, go on to of at different points in attribute this effect to the well-known "not-invented-here" syndrome. According to this explanation, and supported by data reported by themselves and by Pelz and Andrews, groups gradually define themselves 55 t O f'O -.1 LJ D; UI 45 < o Li. a; UI 40 J .35 L. 1? MEAN tenure: OF GROUP MEMBERS Figure 1 , Performance as o Furiction of Mean TerrJi'- of G: OiJp l/lerribers, (Adapted from Peir - UJ LO 3.£ & Andrews. tQTf)) 12 narrow into a have a field of specialization monopoly on knowledge in and convince themselves that they Such increased their area of specialty. specialization creates an appearance to the outside world of decreased relevance, which leads to decrease a communicate with and respond the team's motivation to in As Shoemaker, 1971; Katz and Allen, 1985). expose themselves information (Janis, less and 1972; more narrow focus which less to critical Katz, (Rogers and to the outside world 1982; a long-tenured teams result, sources of external contact and Allen, 1987). It turn leads to poorer performance. in group success often creates the conditions for eventual group has been successful there "winning team" together. conditions may set in this isolation is If is a In sense, When failure. tendency for management a to and a keep the however, this continues for too long which can lead to the observed deterioration in the group's expected performance. PRESENT STUD Y Although relationships between performance and group age now have been reported by at least four different studies, we still know very little about those groups that to maintain creative performance over sustained periods of time. While there may be an "average" tendency decline with higher levels of group age, from which to project groups and still there is performance for- to as yet no empirical basis suggest how one might organize and manage long-term in order to benefit from the continuity of overcome the negative aspects of "NIH," i.e., a team approach of increased insulation, L specialization, stability, and homogeneity (Katz and Allen, 1982 1985). led the of this All sample of of the 181 authors to test the phenomenon further with project teams nine organizations. in study were twofold: a large The primary objectives from this new sample those first to identify long-tenured teams that were able to remain effective over an extended period of time and secondly to try to discover how they were able to accomplish this. In essence, what are some of the particular managerial and organizational factors that significantly differentiate high-performing long-tenured teams from low-performing ones, and what are the group together and creative implications of these findings for keeping a over time? Sample The selection of the nine participating organizations could not be random, but they were chosen industries. the U.S. Two to represent several distinct sectors and of the organizations are Department Space Administration; of Defense the other private industry: one in government laboratories, one in in the National Aeronautics and three are not-for-profit firms doing most of their business with government agencies. in made two in The four remaining organizations are aerospace, one the packaged goods industry. in the electronics industry and Project Performance Since objective measures of performance that are comparable across different technologies have yet to be developed, measure similar to that of many and Katz and Tushman (1967) a subjective including Lawrence and Lorsch studies, each organization, we measured In (1981). we used project performance by interviewing managers who were at least one hierarchical level above the project and functional managers, asking them to indicate on a 5-point Likert-type scale performing above, below, or at whether a project team was the level expected of them, given the particular technical activities on which they were working. Managers evaluated only those projects with which they were personally familiar and knowledgeable. Evaluations were made independently and submitted As confidentially to the investigators. we did in the previously mentioned studies, not prescribe the criteria to be used by the managers, believing that they should employ those criteria that they believed to be most relevant. included, Discussions with the evaluators indicate that the criteria used but were not limited to, schedule, budget, and cost performance; innovativeness; adaptability; and the ability to cooperate with other parts of the organization. On the average, between four and evaluated each project. The evaluations showed very strong consensus within each organization (Spearman- Brown from a five low of 0.74 to a high of 0.93). It is managers internal reliabilities range therefore safe to average the ratings of individual managers to yield reliable project performance scores. In addition to the internal evaluations, 5 an expert panel of independent, outside R&D professionals exhaustively evaluated project base (N=8). The ordering a of their project small subset of our performance evaluations agreed perfectly with the ordering of our own aggregated measures of Such agreement between two separate sources strongly performance. supports the validity of our project performance measures. among distinction between high and low project performance project teams, with a mean performance measures were converted of zero to To clarify the all 181 standardized scores (the original sample mean was 3.32). Team Tenure Over 2,000 individuals questionnaire. in the nine organizations completed The instrument fairly lengthy dealt with a wide range of issues which have been reported elsewhere (Katz L Allen, 1986). a 1985; Among the questions was one which asked each many of Allen & Katz, individual to indicate the exact duration of his association with the project team which was identified on the front page (or of of the questionnaire. Mean team tenure group age) was calculated by iweraging the individual project tenures all project members. There was also a long series of questions dealing with various relationships specific to the project assignment, to the organization In s management, to the individual's work orientation, and each organization, short meetings were scheduled with all so on. members of the technical staff to explain the general purposes of the study, to solicit their voluntary cooperation and to distribute the questionnaire to each 6 Respondents varied engineer individually. mean of 43 age from in 21 to 65 with a and standard deviation of 9.6 years. RESULTS When project performance scores for the 181 projects are standardized and plotted against the mean tenure of project team members, there indication whatever of the curvilinear relationship reported mean of zero so that high range. tenure of There are in the earlier performance scores a large number is line in the entire sample had a In fact, standard deviation units. symmetrical throughout the tenure of low performing projects with mean excess of four years, but there high performers as well. to an and low performance deviations are shown above and below the middle dotted The dispersion no The performance scores have been standardized studies (Figure 3). overall in is is a roughly equal number of the highest performing project team in mean tenure greater than eight years, and two project teams with mean tenures greater than 15 years have performance scores that are more than one standard deviation above the mean. Even when the data are method, as they were in statistically smoothed using Tukey's (1977) 3RSSH our earlier study (Katz & Allen, 1982), no clear pattern emerges (Figure 4). A decay in performance Many inevitable consequence of "group aging"! is therefore not an project teams manage maintain their performance levels with high levels of team tenure. important question now becomes, what 7 is it to The that distinguishes the higher 4 fef- m K t- performing long tenured teams? more closely Project in But first, let us examine the data a comparison with the earlier studies. Type and Comparison with Earlier Results Recent studies suggest that not way they should be managed, R&D all project groups are alike the way they communicate, or in the in in the kinds of tasks they pursue (Allen, et. projects can be categorized along continuum ranging from research development When little a al., 1979; 1980). In particular, to and Tushman, 1981). to technical service (Katz projects are separated into the three types and the data are reanalyzed using the same statistical smoothing process as before, some patterns emerge that at least partially explain some of the curvilinear findings from the earlier studies. differences the patterns shown in There are very in Figures 5, 6 real and and clear 7. In the case of research projects, performance decays after about four years, only to point closer to the me?n return to a "older". Similarly, in in the case of teams that are still the cases of development and technical service teams, there are mean tenure points at which performance drops to fairly low level only to recover to an tenured teams. average or better Whether these patterns really indicate level for longer- something that happening with "middle-aged" teams or whether they are just noise impossible to determine from the present data. the drops in performance occur at different 8 a is is Moreover, the fact that mean tenure points for the R&D © o < a. o LU X I— o o UJ -:> O li: ^^ different project types makes this even more difficult to determine. different patterns, however, may help to explain our inability to simply reproduce previous findings. None of the earlier studies teams whose mean tenure exceeded eight years. whatever causing the decay is These teams of Figures 5 through in It examined project could well be that performance among the "middle-aged" caused the observed decay 7 also in the earlier studies. There are distinct drops and recoveries Figures 5, 6 and These occur 7. each of the three types of R&D in performance that can be seen in at different points for projects within activity: between four and five years for research teams, at two and four years for product development teams, and at three and ten years for technical service teams. pattern to some degree in in One can even our earlier data (Figure 2). performance that occurs between four and six years, be some recovery by the two longest-tenured projects. may be simply spurious or an Nevertheless, in a it is see this Following the drop there appears to Now all of this artifact of the smoothing technique. worth speculating whether there could be certain points team's development that are quite critical. And it may be that at these points some set of relationships develop, both internal and external to the team, that ultimately have a strong effect on the project group's overall performance. The fact that long-tenured project teams exhibit such a substantial variance in performance, some apparently falling victim to the "NIH" 9 syndrome and becoming others maintaining high less effective while performance, provides an opportunity to see what kinds of relationships underlie the variance project team members in a Fortunately, the survey asked performance. number of questions about themselves, their and most importantly, about their relationships with the organization, relationships with both their project and functional management. Comparing High and Low Performing Long Term Project Teams There are a number of interesting ways in which the high performing long-tenured project teams differ from their less successful counterparts. This is particularly true of the way in which the teams relate to both their project and their functional management. Each project team member was asked to evaluate on a seven-point scale both the project manager and the relevant department head or functional manager along a number of leadership management and technical support dimensions related to the of the project. The questions were independently asked for both project and functional managers, affording the opportunity to test the degree to which the responses might be similar or different for each of these managerial roles. Within each team, responses were aggregated separately to obtain overall team measures of project and functional managers that could then be related to project team performance. 10 Role of the Project Manager of the data in Table is I Perhaps the most striking characteristic . the general lack of any strong relationship between the team's perceptions of project manager's characteristics and Only three of the 19 behaviors and the project team's performance. leadership attributes that were measured relate significantly to performance. It role of the project the organization. this is interesting to note that these three is manager in We have argued elsewhere (Katz and the project manager's principal role. little project s relate to the coupling the project team to the rest of especially critical for long-tenured teams. how all direct effect the other project It It is is Allen, 1985) that possible that this role also interesting to see manager attributes have on the performance. Role of Functional Managers Once again, most . of the leadership attributes do not correlate very strongly with performance (Table two significant exceptions are noteworthy, however. relate to the role of the functional underlying technologies. this is role as This is manager in 1985; Allen, 1986; The Both statements as that of connecting to accord with our earlier description of one that manages the technological input (Katz & Allen, II). Allen & Hauptman, to the organization 1987). Long-tenured teams perform better when functional managers provide technical information; maintain currency regarding professional activities; are technically and professionally involved with team high performance standards. In members and maintain short, they function to protect the long- run technical capabilities and competencies of the project team. 11 But as Tabic Project I Manager AUiibuIes and Performance of Long- Icnurcd Project learns Correlation with Project manager project team performance disseminates important and relevant information concerning slale-of-thc art technical advances. manages meetings very is effective in keeping keeps current and is erfeclively. me informed my about well-informed about ihc overall performance. lalcsl professional. has the ability to recogni7e and mediate conflicts between group-: or individuals is an excellent sounding board for new is particularly effective al providing original ideas or fresh approaches. encourages us to participate in ideas. important decisions. RftD has important and useful contacts with other professionals outside this organi/.alion, maintains high standards of performance is heavily involved in the technical details of my work. has been very instrumental in iny professional development and I have learned a great deal from him. has considerable influence which is useful in obtaining the various resources necessary to carry out my work, effectively. provides excellent and constructive feedback on materials and reports has excellent conceptual understanding of is effective al providing appreciation for «ork my my written work. and recognition well done. has important and useful contacts with other R.^'I) professionnl"; within this organization. has a good understanding of ihe applied techniriues and methc\f|s use in my work. I assigns me to jobs or tasks on which professionally to perforin well. I am challrngcd 0.04 Tabic Manager riinclinnal Altriliulc": II and Performance of I nnp-Teniired Project Correlation with team performance Functional manager project disseminates important and relevant information concerning state-of-the-art technical advances manages meetings very is m effective is effectively me informed keeping keeps current and n..-)7 about my overall perforinance. well-informed about the latest professional activities. has the ability to recogni7e and mediate conflicts between groups or individiials- is an excellent sounding board for IS particularly effective a' new ideas. providing oiiginal ideas or fresh approaches. encourages us to participate in important decisions. RScD has impoitani and useful contacts with other Drgani7ation professionals outside this maintains high standard'; of performance, IS heavily involved m the technical details of has been very instrumental a great deal m my my work. professional development and have learned I from him has ccinsiderable influence which is useful in obtaining the various resources necessary to carry nut my work, effectively provides excellent and constructive fccriback on my has excellent conceptual understanding of IS effective at providing appreciation mv written materials and reports work. and recognition for work veil done has iinpoitan! and useful contacts with other RA'I) professionals within this organi7ation. has a good understanding of the applied techniques and methods I use work assigns rne to jobs or tasks on which perform well. I am challenged profcssionalh' to in my long-tenured project teams perform better when the functional manager provides the technological connection, they also need and perform better when the project manager provides a strong organizational connection for integrating and using these technical abilities. Contrast with Newly Formed Groups Given that the leadership roles of project and functional managers are albeit in critical, very different ways, teams, to what degree other teams in performance. to the performance our sample, i.e., long-tenured The such teams? this a characteristic only of is of more newly-formed teams, also vary in Does the differentiation of project and functional roles also explain some of the performance variations in these "younger" teams or are other differences going to be more important? To examine this question, long-tenured teams are compared with more newly-formed teams (mean tenure of degree to which they differ in less than 18 months) to see the terms of how the leadership factors correlate with performance. When this comparison is done, the pattern of overall results can best be seen by simply contrasting the direction of the bars shown in Figures 8 and 9. In in the graphs as each of these figures, the magnitudes and directions of the performance correlations for each of the leadership statements are represented by bars. 12 The correlations for project manager LJ < t- aQ,A Li_l Lu z <;x tL til LiJ m Lt UJ o i-'JLl. X u! X q: Li_l O •< 1— ^ ?;' attributes for both the newly-formed and long tenured teams are shown on the left; those for the functional managers are shown on the right. each side, On "p-values" are displayed when the correlations between "young" and "old" teams are significantly different. What is immediately obvious in these comparisons is newly-formed and long-tenured teams are generally on the project manager side but often functional manager side. is in not true for functional managers. management needs to be in the same direction different directions on the other words, project managers should treat In both "young" and "old" teams similarly This in that the bars for order to foster high performance. The role of functional very different; either more or less pronounced, depending upon how long group members have been working and interacting together. technology and its This is particularly true development. in areas relating to Functional managers need to be much more concerned with providing technical information, professional development opportunities, feedbacl< and challenge, and to insist on high performance standards for project team members who have been away from their specialty departments for extended time periods. 13 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIO NS The notion that both project and functional team performance, but discovery. just What is in different ways, most interesting in is management neither affect project new nor a the present results how important effective functional management may be is a to surprising understand to the performance of long-tenured teams. While the project manager's roles and responsibilities for connecting the project team to the rest of the organization are equally important regardless of the length of time that the team has been working together, the importance of functional management increases with team age. and Allen (1982) have shown that teams tend to their basis of technical knowledge as they age. isolate Pelz themselves from and Andrews (1976) showed that teams prefer narrower, more specialized work, is Katz as they age. It the role of the functional managers to prevent these two effects from developing. The functional managers must insure that those of their staff, who are on longer term project assignments, continue to be well connected to the relevant technologies either directly or indirectly interactions with key technical gatekeepers (Allen, through on-going 1977). Long-tenured team members must also be sufficiently stretched and stimulated to remain broad and open-minded in their approaches to and uses of those technologies 14 Too often, there is a tendency to allow just the opposite longer a department member the less concern there management. This managers devote who are a is is is assigned to They project or series of projects, Functional matrix organizations. in of attention to those not on project assignment or assignments. The happen. for that individual on the part of functional true even lot a to members departments of their who are between project either want to get these people into direct charges (projects) or they have them performing charters of their departments. work which falls (IR&D, for example). As within the a consequence, those who have been given long term, continuing project responsibility and, "taken care of," so to speak often receive less attention until problem emerges. They are a real not on the functional manager's budget, they are well acquainted with their assignments, they are well experienced, and as a result, seem to need less direction functional or even project management. functional in It their is work either from no wonder then that management often forgets about them and that they consequently are allowed to slip easily into the "not invented here" syndrome. The net conclusion to this study is a very simple one. As a team ages, two different but essential leadership roles become increasingly important. There must be strong, influential management to link and integrate the team with the organization's goals, resources, expectations, etc. project manager who must make sure It is that the team has the appropriate attention of the organization and that the team and the organization are 15 the in Research has consistently shown that one of the most synchronization. important factors inhibiting the speed and development of new products the lack of continuity in the focused commitment on the part of the organization to the project team's efforts (Schon, For a is variety of reasons, 1967; including reorganizations, Maidique, 1980). resource reallocations, promotions and reassignments, etc., the continuity of organizational attention is often compromised. development efforts in For example, his in study of long-term the design and manufacturing of semiconductor chips during the 60's and 70's, Vanderslice (1983) showed that there was simply too much rotation of project managers and their organizational counterparts to maintain a continuity of effort that would foster speedy and effective performance. manager, then, is to One of the most important roles of the project make sure that the team continues appropriate attention of the organization and that it is to have the able to interface effectively within this political context. But this managerial role alone is not sufficient to overcome the strong trends toward NIH that often emerge within long-tenured teams. management also needs to be effective functional development of NIH. to There prevent the Functional management has the responsibility to keep their staffs up-to-date and continuously challenged. serious and credible effort for it is a the "technical culture" they try to establish that will ultimately affect the obsolescence, and communication networks This must be of the technical 1986). 16 work orientations, workforce (Allen and Katz, REFERENCES Investigating the not invented here (NIH) and T. Allen (1982) A look at performance, tenure and communication patterns of 12 50 R&D project groups, RS-D Management (1), 7-19. Katz, R. syndrome: , D. Pelz, and Andrews F. , Scientists (1976) Organizations in Ann Arbor: . University of Michigan Press (revised edition). Shepard, H.A. (1956) Creativity R8-D teams. in Research and Engineering , 10-13. Smith, CO. (1970) Relations, 23, 81-92. Age of R&D groups: Organization and Environment Lawrence, P. and J. Lorsch (1967) Harvard Business School. , Boston: An investigation into the managerial R. and M. Tushman (1981) and career paths of gatekeepers and project supervisors in a major Katz, roles R&D A reconsideration, Human facility, R&D Management , H, 3, 103-110. The dual ladder: Motivational solution or Allen, T.J. and R. Katz (1986) managerial delusion? R&D Management 16 2, 185-197. , , Project performance and the locus of Katz, R. and T.J. Allen (1985) influence in the R&D matrix. Academy of Management Journal 28, 1, 67. 87. Tukey, J. (1977) Exploratory Data Analysis . Reading, MA: Addison- Wesley Allen, T.J., M.L. Tushman and D.M. Lee (1979) Technology transfer as function of position in the spectrum from research through development to technical services. Academy of Management Journal 22 (4), 694-708. , , Allen, T.J., D.M. Lee and M.L. Tushman (1980) R&D performance as a function of internal communication, project management and the nature of the work, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 27 (1), 2-12. , , T.J. Managing the Flow of Technology, Cambridge: (1986) Press (revised edition). Allen, Janis, I.L. (1972) Victims of Group Think 17 , Boston: Houghton MIT Mifflin. a Rogers, E.M. and F.I. Shoemaker (1971) The Communication of Innovations: A Cross-Cultural Approach, New York: Free Press. The influence of communication (1987) Allen, T.J. and O. Hauptman A conceptual model. technologies on organizational structure: Communication Research , 14 . (5). 18 h53h 09S Date Due Lib-26-67 U8WARJES ^ "lO&O 005 s 33 &50