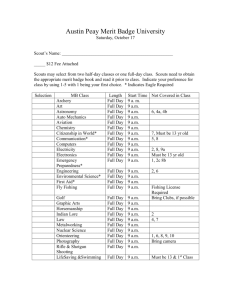

ISS

advertisement