categorical confusion? the strategic implications of recognizing challenges either as irregular or traditional

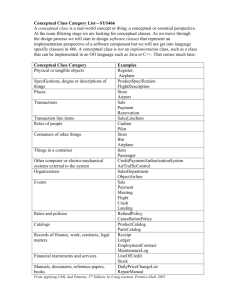

advertisement