Document 11062514

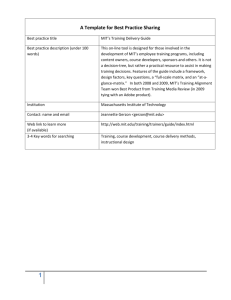

advertisement