GAO DEFENSE MANAGEMENT DOD Needs to

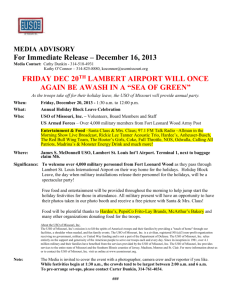

advertisement