GAO

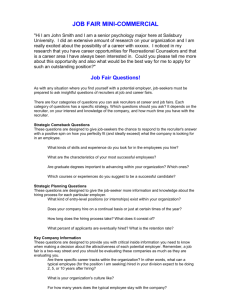

advertisement