GAO INTERNATIONAL FOOD ASSISTANCE Funding Development

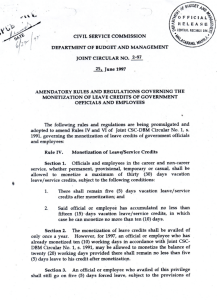

advertisement