OPERATIONAL CONTRACT SUPPORT Additional Actions

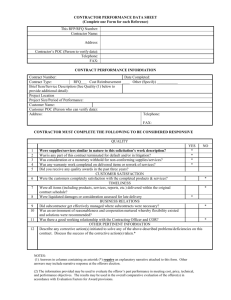

advertisement