GAO DEFENSE ACQUISITIONS DOD Needs to

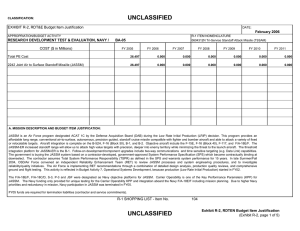

advertisement