January 22, 2008 Congressional Committees

advertisement

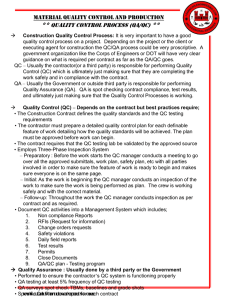

United States Government Accountability Office Washington, DC 20548 January 22, 2008 Congressional Committees Subject: Defense Logistics: The Army Needs to Implement an Effective Management and Oversight Plan for the Equipment Maintenance Contract in Kuwait The Department of Defense (DOD) relies on contractors to perform many of the functions needed to support troops in deployed locations. For example, at Camp Arifjan, Kuwait the Army uses contractors to provide logistics support for operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Contractors at Camp Arifjan refurbish and repair a variety of military vehicles such as the Bradley Fighting Vehicle, armored personnel carriers, and the High-Mobility, Multi-Purpose Wheeled Vehicle (HMMWV). However, while contractors provide valuable support to deployed forces, we have frequently reported that long-standing DOD contract management and oversight problems increase the opportunity for waste and make it more difficult for DOD to ensure that contractors are meeting contract requirements efficiently, effectively, and at a reasonable price. In its fiscal year 2007 report,1 the House Appropriations Committee directed GAO to examine the link between the growth in DOD’s operation and maintenance costs and DOD’s increased reliance on service contracts. In May 2007 we issued a report that examined the trends in operation and maintenance costs at installations within the United States.2 A second report examining the cost impact of using contracts to support deployed forces is expected to be issued in 2008. In the interim, we are issuing this report to you on the Army’s Global Maintenance and Supply Services (GMASS) contract’s multimillion-dollar Kuwait task order—Task Order 1—because of the findings we uncovered during this engagement and the implications for waste of taxpayer dollars and the potential negative impact on the warfighter as well as on our redeployment from Iraq once a decision is made to do so. This report discusses information about Task Order 1 that we developed during our review. Our objectives were to (1) evaluate the contractor’s performance of maintenance and supply services under Task Order 1, (2) determine the extent to which the Army’s quality assurance and contract management activities implement key principles of quality assurance and contract management regulations and 1 H.R. Rep. No. 109-504, at 46-47 (2006). GAO, Defense Budget: Trends in Operations and Maintenance Costs and Support Services Contracting, GAO-07-631 (Washington, D.C.: May 18, 2007). 2 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics guidance, and (3) determine the extent to which the Army is adequately staffed to perform oversight activities. To evaluate the contractor’s performance under Task Order 1, we interviewed contractor officials at Camp Arifjan, Kuwait as well as Army officials at the Army Sustainment Command in Rock Island, Illinois and at the 401st Army Field Support Battalion in Camp Arifjan, Kuwait. We also reviewed various Army and contractor documents related to contractor execution, analyzed Army provided data to compute pass/fail percentages, and observed the contractor’s maintenance processes. To determine the extent to which the Army’s quality assurance and contract management activities implement key principles of quality assurance and contract management regulations, we met with contracting and quality assurance officials at Camp Arifjan, Kuwait, and Rock Island, Illinois, and reviewed various oversight and surveillance documents. We also observed physical inspections of equipment presented to the Army and analyzed Army-provided data on oversight and surveillance. To determine if the battalion was adequately staffed to perform oversight activities, we reviewed battalion staffing documents, spoke with battalion oversight and command officials, and reviewed DOD and Army guidance and regulations regarding contract oversight and management. Although data used to compute pass/fail percentages did not include all failures, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our review. We conducted this performance audit from March 2007 through October 2007 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Enclosure I is a detailed discussion of our scope and methodology. Results in Brief Since the inception of Task Order 1, the contractor has had difficulties meeting maintenance standards, maintaining an accurate database, and meeting production requirements. According to Task Order 1, the contractor shall ensure that equipment is repaired to specified Army standards. However, in many cases, the equipment presented to the Army as ready for acceptance failed government inspection. Army corrective action reports attributed these performance shortcomings to problems with the contractor’s quality control processes and other factors. First, our analysis of Army data found that for five types of vehicles inspected by quality assurance personnel from July 2006 through May 2007, 18 to 31 percent of the equipment presented to the Army as ready for acceptance failed government inspection. In addition, some equipment presented to the Army as ready for acceptance failed government inspection multiple times, sometimes for the same deficiencies. Army officials believed the contractor’s quality control system used to ensure that equipment met specified Army standards was poor and the contractor depended on the Army to identify equipment deficiencies. When the Army inspected equipment that did not meet standards, it was returned to the contractor for continued repair. Our analysis of Army data found that since May 2005 an additional 188,000 hours were worked on equipment after the first failed government inspection, which translates into an additional cost of approximately $4.2 million. Furthermore, the Page 2 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics contractor was required to operate wash racks to clean equipment in preparation for its transport back to the United States. However, according to DOD inspectors, equipment that was presented for inspection frequently did not meet cleaning standards referenced in Task Order 1. Second, although the contractor is required to ensure the correct equipment condition code and location are entered into a maintenance management database, on numerous occasions Army officials found that incorrect status was assigned to equipment within the database. For example, on one occasion, the contractor coded a HMMWV as “ready for issue”; however, when the Army went to issue the vehicle it was in a maintenance shop being repaired by the contractor. Among the reasons the contractor gave for problems with the database included human error and a fault in the way the database handles certain data. According to the contracting office, erroneous equipment status reporting affects the battalion’s ability to make timely and accurate decisions regarding the availability of equipment to support the warfighter. Third, according to the Army, the contractor has not met some production requirements and deadlines for some tasks were extended. For example, according to the Army, the contractor failed to meet the monthly production requirement for a HMMWV refurbishment effort. According to a contracting official, a lack of contractor standard operating procedures and a lack of in-process quality checks led to a high number of equipment defects, thereby delaying Army acceptance of the HMMWVs. In addition, the contractor was unable to independently meet certain production deadlines set by the Army. For example, the contractor was unable to meet a deadline for repairing equipment for the Iraq security forces without government assistance. Poor contractor performance may result in the warfighter not receiving equipment in a timely manner. The quality assurance and contract management actions taken by the 401st Field Support Battalion make it difficult for the battalion to meet several key principles detailed in the Army Quality Program regulation and other DOD quality assurance principles. These principles include, (1) using demonstrated past performance in riskbased planning, (2) identifying recurring contractor performance issues, and (3) using past performance information as an evaluation factor for future contract awards. For example, we found that the battalion does not always document deficiencies identified during its quality assurance inspections. Instead, quality assurance inspectors were allowing the contractor to fix some deficiencies without documenting them in an attempt to prevent a delay in getting the equipment up to standard to pass inspection. In addition, although the battalion’s July 2006 draft maintenance management plan requires that contractor performance data be analyzed to help identify the cause of recurring quality problems and evaluate the contractor’s performance, the Army did not begin to review the contractor’s performance data until July 2007. We found that although data on contractor performance were readily available, the battalion was not routinely tracking or monitoring the percentage of equipment submitted for government acceptance that failed quality assurance inspection. Furthermore, we found that in May 2006, the Army awarded the contractor a major HMMWV refurbishment effort, valued at approximately $33 million, even though numerous incidents of poor contractor performance had been documented. According to the contracting officer, the Army believed the contractor was fully engaged in correcting poor performance issues. Until the 401st Army Field Support Battalion implements the quality and management procedures in its quality and management plans, it will be unable to determine the extent to which the contractor is meeting the contract requirements and will be Page 3 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics unable to identify problem areas in the contractor’s processes and initiate corrective action to ensure that deployed forces are receiving equipment in a timely manner. Our analysis indicates that the Army is inadequately staffed to conduct oversight of Task Order 1. Authorized oversight personnel positions vacant at the time of our visit in April 2007 included those of a quality assurance specialist, a property administrator, and two quality assurance inspectors. The contracting officer told us that the two civilian positions (the quality assurance specialist and the property administrator) had been advertised but the command had not been able to fill the positions with qualified candidates. The battalion was unsure why the two military positions (the quality assurance inspectors) had not been filled. The lack of an adequate contract oversight staff is not unique to this location. We have previously reported on the inadequate number of contract oversight personnel throughout DOD, including at deployed locations. Army officials also told us that in addition to the two quality assurance inspectors needed to fill the vacant positions, additional quality assurance inspectors were needed to fully meet the oversight mission. According to battalion officials, vacant and reduced inspector and analyst positions mean that surveillance is not being performed sufficiently in some areas and the Army is less able to perform data analyses, identify trends in contractor performance, and improve quality processes. Also, the Army is considering moving major elements of option year 3 (including maintenance and supply services) to a cost plus award-fee structure beginning January 1, 2008. Administration for cost plus award-fee contracts involves substantially more effort over the life of a contract than for fixed-fee contracts. Without adequate staff to monitor and accurately document contractor performance, analyze data gathered, and provide input to the award-fee board, it will be difficult for the Army to effectively administer a cost plus award-fee contract beginning in January 2008. Accordingly, we are making recommendations to the Secretary of Defense to direct the Army to review and evaluate its procedures for managing and overseeing the GMASS task order for services in Kuwait and take the necessary actions to improve contract management and address the issues raised in this report. The Army should take the steps necessary to effectively implement its management and oversight plan to ensure quality maintenance work by the contractor and proper administration of the cost plus award-fee contract. In commenting on a draft of this report, DOD concurred with our recommendations and discussed proposed implementation actions to be taken by the Army. DOD’s comments are reprinted in enclosure II. Background In March 2004, Army Field Support Command (now the Army Sustainment Command) issued a solicitation to provide maintenance and supply services in support of Army Materiel Command, Army Field Support Command, coalition forces, and other authorized government agencies. In October 2004, the Army awarded three indefinite quantity/indefinite delivery-contracts3 for GMASS. The Army 3 There are three types of indefinite-delivery contracts: definite-quantity contracts, requirements contracts, and indefinite-quantity contracts. The appropriate type of indefinite-delivery contract may Page 4 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics simultaneously issued Task Order 14 for maintenance services at Camp Arifjan. Task Order 1 contains several different types of contract line items, including cost plus fixed fee and firm-fixed-price provisions.5 For those provisions that are cost plus fixed fee, payment of a negotiated fee that is fixed at the inception of the task order is made to the contractor.6 The fixed fee does not vary with the actual costs but may be adjusted as a result of changes in the work to be performed. This permits contracting for efforts that might otherwise present too great a risk to contractors, but provides the contractor only a minimum incentive to control costs and, in turn, provides the greatest risk to the government. In addition, the Army cannot adjust the amount of fee paid to contractors based on the contractors’ performance for the cost plus fixed fee provisions. For those provisions in the task order that are firm fixed price, the contractor has full responsibility for the performance costs and resulting profit or loss. Task Order 1 was for 1 year and was originally valued at $20,354,256. However, by the end of the base year Task Order 1 costs increased to approximately $102 million. The Army has exercised three options under the contract and Task Order 1. Costs for option years 1 and 2 were $209.6 million and $269.4 million, respectively. Cumulative obligations for the base year plus option years 1 and 2 were approximately $581.5 million.7 There have been at least 86 modifications to the contract and Task Order 1, including some that added requirements, such as Army prepositioned stock reset, a tire assembly and repair program, and HMMWV refurbishment. Many of the modifications were administrative, such as providing additional funding, extending performance work periods, updating contract line item numbers, and fixing typographical errors. Administration and oversight of this contract is the responsibility of the contracting officer located at the Army Sustainment Command in Rock Island, Illinois. According to the Federal Acquisition Regulation, contracting officers are responsible for ensuring performance of all necessary actions for effective contracting, ensuring compliance with the terms of the contract, and safeguarding the interests of the United States in its contractual relationships. For Task Order 1, the contracting officer has delegated some administrative control of the contract and task order to administrative contracting officers located in Kuwait. The primary administrative contracting officer has contract administrative responsibilities for most of the tasks included in Task Order 1 and serves as the lead person for the battalion’s contract be used to acquire supplies, services, or both when the exact times, exact quantities, or both of future deliveries are not known at the time of contract award. An indefinite-quantity contract provides for an indefinite quantity, within stated limits, of supplies or services during a fixed period. FAR §§ 16.501-2, 16.504 4 Under the solicitation, the minimum guaranteed award to the primary awardee included, among other things, maintenance and supply services performed at Camp Arifjan, Kuwait. Task Order 1 was issued to the primary awardee under the solicitation. 5 Some contract line item numbers are cost plus fixed fee and others are firm fixed price. The contract line item numbers for the maintenance work were cost plus fixed fee. 6 According to the Federal Acquisition Regulation, cost reimbursement contracts provide for payment of allowable incurred cost, to the extent prescribed in the contract. These contracts establish an estimate of total cost for the purpose of obligating funds and establishing a ceiling that the contractor may not exceed (except at its own risk) without the approval of the contracting officer. FAR § 16.3011. 7 These costs do not include the cost of repair parts as they are provided by the government. Page 5 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics oversight team, which includes a government property administrator, quality assurance specialist, and contract management officer. The contract oversight team also includes five contracting officer representatives designated for specific areas of oversight including transportation, maintenance, supply, and operations. Within the specific areas, quality assurance inspectors perform inspections of the contractor’s work. Quality assurance personnel at Camp Arifjan perform oversight of the contractor’s work using a quality assurance surveillance plan. This plan, based on requirements contained in Task Order 1, is developed by the Army and is used to ensure that systematic quality assurance methods are used to monitor and evaluate the performance and services of the contractor. It describes the surveillance schedule, methods, and performance measures. As stated in the contract quality assurance surveillance plan, the level of government quality assurance oversight is determined by contractor performance. Specifically, the number of quality assurance inspections may be increased, if deemed appropriate, because of repeated failures discovered during quality assurance inspections. Likewise, the government may decrease the number of quality assurance inspections if performance dictates. While the contractor, and not the government, is responsible for the management and quality control actions to meet the terms of the contract, the government quality assurance surveillance plan was put in place to provide government surveillance oversight of the contractor’s quality control efforts to ensure that they are timely and effective and are delivering the results specified in the contract. As a part of the battalion’s surveillance process, 100 percent of equipment repaired by the contractor is inspected by quality assurance inspectors prior to being accepted. When the contractor informs the Army that equipment is ready to be inspected, the inspectors review the equipment for compliance with applicable maintenance standards. According to battalion standard operating procedures, all deficiencies identified through Army quality assurance inspections that prohibit the equipment from meeting the established maintenance standards shall be documented. Documented deficiencies describe the items that must be fixed by the contractor in order for the equipment to meet the maintenance standards and indicate that the equipment failed the Army quality assurance inspection. The Army has developed a problem escalation and resolution process that provides guidance for dealing with problems with a contractor. According to the process, an identified problem that is not considered severe should be documented by the administrative contracting officer in a corrective action report to the contractor with a deadline for addressing the problem. The process defines severe as a problem related to safety, security, environmental, or mission impact or the third occurrence of the same minor problem. If the problem is determined to be severe, the administrative contracting officer in coordination with the contracting officer should take immediate action to address any unsafe practice and issue a contract deficiency report to the contractor. When identified problems are not corrected after issuance of a contract deficiency report, the situation is to be elevated to the contracting officer. If informal communication with the contractor from the contracting officer cannot resolve the problem, the contracting officer is to issue a formal notice to the contractor, allowing 10 days for a response. Records of all corrective action reports and contract deficiency reports should be provided to the contracting officer. Page 6 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics The Contractor Has Had Difficulties Meeting Maintenance Standards, Maintaining an Accurate Database, and Meeting Production Requirements Our work highlights the difficulties the contractor has had under Task Order 1 in meeting maintenance standards, maintaining an accurate database, and meeting production requirements. First, in analyzing Army data, we found that from July 2006 through May 2007, 18 to 31 percent of five types of vehicles presented by the contractor to the Army as ready for acceptance had not been repaired and maintained to the standards specified in Task Order 1 and consequently failed government inspection.8 In addition, agricultural inspectors stated that contractor-cleaned equipment that was to be transported back to the United States frequently did not meet certain agricultural standards. Second, the database into which the contractor was required to enter the equipment’s condition codes and location contained inaccurate information about equipment status. On numerous occasions, equipment was coded as ready to issue when it had not passed quality assurance inspection. According to a corrective action report issued to the contractor, a HMMWV was coded as ready to issue; however, when a unit went to draw the vehicle, it was in a repair facility. Third, according to the Army, the contractor had missed production requirements and originally established deadlines for some tasks. For example, Army officials stated that during the 12 months of a major HMMWV refurbishment operation, the contractor never met the monthly production requirement. Equipment Presented to the Army for Acceptance Frequently Did Not Meet Maintenance Standards Referenced in Task Order 1 The contractor frequently presented equipment to the Army for acceptance that did not meet the Army standards referenced in Task Order 1. According to Task Order 1, the contractor shall ensure that equipment is repaired to specified Army standards determined by the government. Further, the contractor was to ensure that quality control inspections and maintenance repair of materiel deficiencies were completed. However, the contractor frequently presented equipment to the Army that did not meet Army standards. When the contractor completes maintenance on a piece of equipment, it is submitted to the Army as ready for acceptance and Army quality assurance personnel inspect the equipment to ensure that it meets specified maintenance standards. Army quality assurance officials told us that in many cases the contractor presented equipment to the Army as ready for acceptance that failed Army inspection because the equipment did not meet the established maintenance standards. In February 2007 we issued a report on the condition of the Army’s pre-positioned equipment located at various sites around the world. As part of that engagement, we visited Camp Arifjan in June 2006 to determine the condition of the equipment maintained by the Task Order 1 contractor. In our February report, we noted that 28 percent of the equipment at Camp Arifjan submitted for government acceptance had failed quality assurance testing from June 2005 through June 2006.9 In the spring of 8 While Task Order 1’s Statement of Work did not contain a first pass yield rate requirement, it did require that the contractor repair all equipment to certain Army standards. Therefore, we view pass/fail rates as an indicator of the quality of the contractor’s performance in repairing equipment to Army standards. 9 GAO, Defense Logistics, Improved Oversight and Increased Coordination Needed to Ensure Viability of the Army’s Prepositioned Strategy, GAO-07-144 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 15, 2007). Page 7 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics 2007 we returned to Camp Arifjan and found similar failure rates. As shown in table 1, our analysis of Army data found that for five types of vehicles inspected by quality assurance personnel from July 2006 through May 2007, the percentage of equipment presented to the Army as ready for acceptance but that failed government inspection ranged from 18 to 31 percent.10 Table 1: Failure Rate Percentages for Selected Equipment Types Inspected from July 2006 through May 2007 Number of Number of Equipment type inspections Percentage failed failures performed M113 Armored 109 20 18 Personnel Carrier M2A2 Bradley 404 110 27 M1025 and M1026 934 255 27 HMMWV M1070 Heavy Equipment 248 76 31 Transporter Heavy Expanded Mobility Tactical 460 122 27 Truck Source: GAO analysis of Army data. Similarly, in July 2007 the 401st Army Field Support Battalion began calculating (by commodity group) the percentage of equipment that failed government inspection each week basis.11 The battalion’s analysis found the percentage of vehicles failing quality assurance inspection generally ranged from 23 and 32 percent in August and September 2007 with a high of just over 55 percent in 1 week. Analyzing the Army’s maintenance data, we also found that 702 pieces of equipment failed Army quality assurance inspection three or more times since May 2005. One example is an ambulance HMMWV that failed Army quality assurance inspection five times in December 2006. This vehicle repeatedly failed inspection for a leaking heater hose and a leaking valve cover. In another example, a Bradley Fighting Vehicle failed quality assurance inspection three times. During the first inspection, 12 deficiencies, including 5 that made the vehicle inoperable, were identified and documented. One of the inoperable deficiencies discovered was a main electrical system ground that was installed improperly, creating a safety hazard. In the second and third inspections, multiple deficiencies that made the vehicle inoperable continued to be found, some of which were the same deficiencies that had been previously identified. Moreover, for the HMMWV refurbishment task, the contractor frequently presented vehicles to the Army with multiple deficiencies. For the 5 month period from November 2006 through March 2007, multiple deficiencies were identified through 10 As discussed later in this report, not all deficiencies are documented to illustrate that equipment failed Army quality assurance inspection. As a result, these numbers may be understated. 11 The commodities include vehicles, small arms, ground support equipment, atmospheric test, high dollar part verification, and paint inspection. Page 8 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics government inspection of refurbished HMMWVs when presented to the Army for acceptance. During those months, the average number of deficiencies identified per vehicle through quality assurance inspection ranged from 2.5 to 7.4 per month. The following inspections, which we observed during our visit to Camp Arifjan in spring 2007, illustrate the difficulties the contractor has had meeting Army maintenance standards. While at Camp Arifjan we observed four government equipment inspections, two of which failed. One failed inspection was of a Bradley Fighting Vehicle. The Bradley was presented to the Army as ready for acceptance; however, during the quality assurance inspection the inspector found that a cotter pin was missing. This pin holds an adjusting rod that controls the brakes on one side of the Bradley. According to the inspector, using the brakes just two or three times would have caused the rod to come loose, leaving the Bradley without brakes. A second failed inspection we observed was of a forklift. Because of a burned fuse, the forklift did not meet the maintenance standard and therefore failed the inspection. The burned fuse was clearly visible to us and should have been easily seen by contractor personnel.12 In a March 2006 letter to the contractor, the Army expressed concerns about the contractor’s quality control department. Specifically, the Army stated that there was a lack of attention to detail and inadequate maintenance inspection processes and that quality control personnel were not ensuring that maintenance repairs were in compliance with the appropriate maintenance manuals. Additionally, in some corrective action reports issued after the March 2006 letter the Army continued to express concern about the contractor’s quality control processes. Specifically, the battalion noted that the contractor’s quality control inspections were not being performed in accordance with Army maintenance standards and that the contractor’s quality control checks were not adequate. Army quality assurance officials believed that the contractor depended on the Army to identify equipment deficiencies. As a result of these issues, government quality assurance inspectors were consistently rejecting equipment presented as ready for acceptance. When equipment is presented to the government and does not pass quality assurance inspection, it is returned to the contractor for continued maintenance until it meets the established standard. Under the cost plus fixed fee maintenance provisions in Task Order 1, the contractor is reimbursed for all maintenance labor hours incurred, including labor hours associated with maintenance performed after the Army rejects equipment that fails to meet Army maintenance standards. This results in additional cost to the government. For example, in a December 2006 quality assurance inspection of a HMMWV, 16 deficiencies that made the vehicle inoperable were found. According to Army data, a total of 213 hours were spent working on this vehicle after it was initially submitted to the government as ready for acceptance. A 12 In commenting on our draft report, the contractor argued that the quality assurance surveillance plan gave government quality assurance inspectors no guidance on how to determine whether a particular piece of equipment passed or failed maintenance standards. Government quality assurance inspectors use the technical manual for the specific piece of equipment to determine whether the equipment passes or fails inspection. These manuals are also what the contractor’s chief quality representatives said they use to repair and inspect the equipment. Also, for the maintenance area, government quality assurance inspectors are trained mechanics with technical expertise related to the equipment being inspected. Page 9 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics second example is a Heavy Equipment Transporter (HET) that was submitted to the Army as ready for acceptance in January 2007 and failed Army inspection. After this first failed inspection, an additional 636 hours were charged for repairing this vehicle before it passed government quality assurance inspection 3 months later. Although the equipment was not initially presented to the Army at the required standard, the Army reimbursed the contractor for the labor costs associated with the 213 and 636 hours of rework. Our analysis of Army data found that since May 2005, the contractor worked a total of about 188,000 hours to repair equipment after the first failed government inspection. This translates into an approximate cost to the government of $4.2 million.13 As part of the maintenance requirements of Task Order 1, the contractor was required to conduct wash rack operations in preparing equipment for shipment to the United States. According to Task Order 1, the contractor was required to clean equipment to meet the appropriate agricultural standards14 as directed by the government. Further, Task Order 1 noted that the Department of Agriculture’s Animal Plant Health and Inspection Service (APHIS) regulations call for the equipment to be clean of soil, organic matter, and other contaminants.15 According to Navy customs inspectors,16 equipment presented for inspection frequently did not meet APHIS standards. The inspectors were unable to provide historical data on agricultural inspection results because they had just begun to track and monitor this performance metric. However, the officials told us that they reject most equipment at least once due to the presence of mud and dirt. We observed an inspection in which a contractor employee was trying to remove water from the interior of a piece of equipment with his hands and the vehicle tracks were clearly filled with mud. Contractor-Maintained Database Contains Inaccurate Information about Equipment Status The contractor-maintained database contains inaccurate information about equipment status. The database is used for tasks that include, but are not limited to, equipment maintenance status, scheduling equipment for maintenance, deficiency reporting, parts management, labor reporting, and materiel expenses. Among other things, Task Order 1 requires the contractor to ensure that correct equipment condition codes and correct locations of equipment be entered into the database in accordance with Army policy. However, on numerous occasions, Army officials found that incorrect condition codes were assigned to various pieces of equipment within the database. In some instances, equipment was coded as ready for issuance when it had not passed quality assurance inspection. For example, according to a corrective action report issued to the contractor, in the maintenance database the contractor reported that a HMMWV was ready for issuance, but when the Army went to issue this vehicle to a unit, it was in a maintenance shop being repaired by the contractor. In another instance, the contractor had coded equipment that had not 13 As discussed later in this report, not all deficiencies are documented to illustrate that the equipment failed Army quality assurance inspection. As a result, these numbers may be understated. 14 Task Order 1 specifies that these cleaning standards are in accordance with DODD 4500.9, DOD 5030.49-R, and ARCENT Directive 30-3. 15 7 C.F.R. Part 330. 16 Navy customs officials serve as U.S. Customs border clearance agents. They inspect material and personnel returning to U. S. Customs territory. Page 10 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics passed Army quality assurance inspection as ready for issuance and placed the equipment in a staging area for Heavy Brigade Combat Team equipment that was ready for issue. According to the battalion, this inaccurate reporting portrayed an incorrect readiness posture for the combat team and could have resulted in a crippling slowdown of the equipment issue process due to the probability of units rejecting the equipment. The battalion issued corrective action reports to the contractor stating that (1) the database was not being updated with proper condition codes and (2) erroneous data may have been reported to the Department of the Army in the battalion’s operational readiness reports. Additionally, in an assessment of the contractor’s performance in option year 1, the contracting office stated that erroneous equipment status reporting potentially affects the battalion’s ability to make timely and accurate decisions regarding the availability of equipment to support the warfighter. Among the reasons the contractor gave for the incorrect condition codes in the database were human error and a probable fault in the manner in which the database handles certain data. According to the Army, the Contractor Has Missed Production Requirements and Deadlines According to the Army, the contractor has missed some production requirements and some task deadlines were extended when the contractor was unable to meet original completion dates.17 In May 2006 a task was added to the contract for the refurbishment of HMMWVs. The statement of work associated with the HMMWV refurbishment effort stated that the contractor was required to be able to process the HMMWVs through the maintenance facilities at a minimum rate of 150 HMMWVs per month. According to documents provided by the contracting officer, upon award of this work, the contractor was provided 45 days to become fully operational, and for months one and two of operations the production requirement was 25 and 100 vehicles, respectively. According to Army documents, after the first 2 months of operation, the contractor was expected to be fully operational and the monthly production requirement was increased to 150 vehicles per month. However, 18 and 90 HMMWVs were completed in the first and second months of operations, respectively. Further, according to the Army, the contractor failed to meet its contractual requirement of a minimum of 150 vehicles per month, and the contracting officer sent written notices to the contractor documenting this failure. In some months fewer than 75 HMMWVs were ultimately accepted by the Army, as shown in table 2 below. For example, 38 vehicles were accepted by the Army in February 2007. According to an e-mail from one of the administrative contracting officers, the contractor’s monthly production output was influenced by issues such as deficient production processes and supply management, quality control, and parts availability problems. The official cited a lack of contractor standard operating procedures and in-process quality checks as reasons for a high number of equipment defects, thereby delaying Army acceptance of the HMMWVS. Further, the official cited contractor supply management challenges, such as determining when to order additional parts and 17 The broad scope of Task Order 1 allows the Army to add maintenance tasks when necessary. Some tasks like the repair of battle-damaged equipment or the preparation of equipment for return to the United States are on-going tasks for the contract period of performance; other tasks have specific deadlines established by contract modification. For example, preparing equipment to issue to units supporting the surge and repairing equipment to be used in Iraq, as well as the two mentioned in this correspondence are tasks with specific deadlines. Page 11 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics ordering the right amount of parts in a timely manner, as affecting the contractor’s ability to meet monthly production requirements. The official acknowledged that the parts availability problem was driven by a shortage of armor and frame rails in the Army supply system. Army officials stated that as a result of the contractor’s failure to meet the production requirements of the HMMWV refurbishment effort, the Army did not renew this task with the contractor at the end of the performance period. Because this was a fixed fee provision, the Army was not able to reduce the contractor’s fee for this task. Table 2: HMMWV Refurbishment Center Monthly Production Number of vehicles accepted Production month by the Army June 2006 18 July 2006 90 August 2006 80 September 2006 60 October 2006 111 November 2006 105 December 2006 54 January 2007 70 February 2007 38 March 2007 40 April 2007 60 Source: GAO analysis of Army data We also found that the contractor was unable to independently meet the original deadlines set by the Army for two other tasks. In July 2006 the contractor began a task to repair 150 HETs. The original completion date for this task was September 29, 2006; however, as of that date only 96 HETs had been accepted by the Army. While the original completion date was pushed back at the mutual agreement of the contractor and the government, Army contracting officials explained that the original completion date for this task was extended because of the contractor’s inability to provide the required 150 HETs by the date originally specified in Task Order 1. The contractor also had a task to repair HMMWVs for foreign military sale to the Iraqi security forces. This task required the contractor provide a specific number of HMMWVs during four different periods. According to the contracting officer’s assessment of the contractor’s performance, the contractor was unable to meet the requirements independently and government assistance was necessary. The contractor stated that this condition was caused by a lack of government-provided critical parts and inbound vehicles. According to a battalion official, the battalion allowed the contractor to use HMMWVs that the battalion planned to use to meet other missions. At the time the contractor was preparing HMMWVs for the Iraqi security forces, among the battalion’s other missions were repairing and replacing equipment damaged as a result of combat and preparing equipment for a light brigade combat team. The battalion officials stated that while using assets designated for other missions allowed the contractor to meet the requirements of the Iraqi security forces task, the contractor had to subsequently back fill those sources. Problems meeting production and quality goals may have resulted in some deployed units not receiving the equipment they needed in a timely manner. Page 12 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics The Army Has Not Always Followed Established Quality Assurance Principles The Army has not always followed key quality assurance and contract management principles when managing Task Order 1 because it did not implement the processes contained in its quality assurance and contract management plans. These processes require that contractor performance data be documented and used to assess contractor performance, identify recurring problems, and inform contract management decisions. However, the Army has not always documented deficiencies identified during the battalion’s quality assurance inspections, instead allowing the contractor to fix some deficiencies without documenting them in an attempt to prevent a delay in getting the equipment to pass inspection. In addition, the Army did not analyze available data to evaluate the contractor’s performance, failing to routinely track or monitor the percentage of equipment submitted for government acceptance that failed quality assurance inspection until July 2007. Furthermore, the Army awarded the contractor a major HMMWV refurbishment effort, valued at approximately $33 million, even though numerous incidents of poor contractor performance had been documented. Army and DOD Quality Assurance and Contract Management Principles Should Guide Battalion Activities The Army and DOD have developed a variety of quality assurance and contract management principles that should guide the battalion quality and contract management activities. The Army Quality Program is a results-based program that allows Army activities to develop their own quality programs. However, the program regulation states that quality programs will address the following key principles: • Measurement and verification of conformity to requirements • Fact-based decision making • Use of performance information to foster continuous improvement • Effective root-cause analysis and corrective action • Performance of tasks by people who can evaluate quality issues and recommend solutions In addition, according to the Army Quality Program regulation, an activity’s (such as the battalion’s) quality assurance program should utilize risk-based planning. In determining the types and frequency of quality assurance actions, the activity should consider the impact of nonconforming equipment or services as well as the contractor’s demonstrated past performance. DOD guidance also establishes principles for quality assurance and contract administration. For example, according to the guidebook for performance-based service acquisitions in DOD, each performance assessment activity should be documented as it is conducted, whether a contractor’s performance was acceptable or unacceptable in accordance with the performance assessment plan. In addition, the Federal Acquisition Regulation requires that contractor performance be documented and that past performance be considered when selecting contractors for future contract awards. Page 13 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics The Army Does Not Always Document Poor Performance The Army has not always documented unacceptable contractor performance under Task Order 1. The collection of performance data is the foundation for many of the quality and contract management requirements established by Army and DOD regulations and guidance. For example, the Army regulation establishing the Army Quality Program requires that actions be taken to identify, correct, and prevent the recurrence of quality issues. Furthermore, the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement states that the contract administration office shall establish a system for the collection, evaluation, and use of certain quality data, including quality data developed by the government through contract quality assurance actions. Moreover, the battalion’s quality assurance guidance requires that deficiencies identified through the battalion’s inspections be documented. However, some deficiencies identified during Army inspection of equipment were not being documented and entered into the Army maintenance database. According to battalion quality assurance officials, while deficiencies that made the equipment inoperable were always documented, deficiencies that did not make the equipment inoperable but kept it from meeting the maintenance standards were commonly not documented. Rather than documenting all the deficiencies identified, quality assurance inspectors were allowing the contractor to fix some deficiencies without documenting them, in an attempt to prevent a delay in getting the equipment up to standard and passing inspection. According to quality assurance officials, it may take an additional half a day to 1 day for equipment to be accepted by the Army when deficiencies that do not make the equipment inoperable are documented, because of the paperwork and process associated with correcting documented deficiencies. Although the Army took steps to correct the lack of documentation for all equipment deficiencies, it reverted back to its original process of not documenting all deficiencies. Based on our review, the Army took steps in May 2007 to ensure the documentation of all equipment deficiencies identified during Army quality assurance inspections. The lead quality assurance official directed that all equipment deficiencies be documented so that the Army would have an accurate picture of the contractor’s maintenance quality. We were later told by quality assurance officials that inspectors followed this direction and documented all equipment deficiencies that were identified during inspections for approximately 2 weeks. However, the officials stated that after about 2 weeks the inspectors went back to the practice of allowing the contractor to correct those deficiencies that did not make the equipment inoperable without documenting them. They cited the need to get the equipment to the units quickly as the reason for doing this. When contractor performance is poor, the need for rigorous government quality assurance oversight becomes even more important. We believe that the deficiencies can be documented without a delay in getting the equipment to the units. For example, the inspector can document the deficiencies identified during the inspection on the appropriate worksheet, and at the end of the inspection it can be noted that the deficiencies were corrected. This worksheet would be included in the equipment packet provided to the personnel responsible for updating the equipment status codes in the maintenance database. When the equipment status code is updated in the maintenance database, it should be noted that deficiencies were identified and were corrected, and that the equipment subsequently passed quality assurance inspection and is ready for issuance. Page 14 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics The Army Did Not Analyze Available Data to Evaluate Contractor Performance until July 2007 The Army did not analyze available data to evaluate the contractor’s performance in meeting the specified maintenance standard requirements until July 2007. The Army quality program specifies the use of performance information to perform root-cause analysis and foster continuous improvement, and the battalion’s July 2006 draft maintenance management plan requires that contractor performance data be analyzed to help identify the cause of new and/or recurring quality problems and evaluate the contractor’s performance. As previously mentioned, Army quality assurance personnel inspect equipment submitted for Army acceptance to ensure that it meets the specified maintenance standards. The results of these inspections, including data documenting whether the equipment has been accepted or rejected by the Army, are maintained by quality assurance officials as well as in the Army maintenance database. However, in February 2007, we reported that the maintenance battalion had not routinely tracked or monitored the percentage of equipment submitted for government acceptance that failed quality assurance inspection.18 While we found that the inspection results data were readily available to the maintenance battalion, it was still not tracking or monitoring this key performance metric. Because the battalion does not track and monitor the percentage of equipment submitted for Army acceptance that failed quality assurance inspection, the Army does not know the extent to which the contractor is meeting the specified maintenance standard requirements nor can it identify problem areas in the contractor’s processes and initiate corrective action. According to Army quality assurance officials, this metric was not tracked and monitored because they did not have sufficient quality assurance staff to perform such analysis. Recognizing the usefulness of this performance metric, the lead quality assurance inspector informed us that in July 2007, he began calculating the percentage of equipment that is failing quality assurance inspection each week, and this information is presented to the battalion commander at command and staff updates. He said that this information is used to identify maintenance shops that are not improving their performance and to develop historical data on the contractor’s performance. In the past, the command has initiated improved oversight practices but has later discontinued them. Maintaining the practice of tracking and monitoring performance metrics would provide key data for assessing the contractor’s performance. The Army Awarded Additional Work to the Contractor despite Performance Concerns In May 2006, the Army added a major HMMWV refurbishment effort valued at approximately $33 million to Task Order 1 despite concerns of poor contractor performance. According to contracting officials, Task Order 1 provided an existing contract that could be used to expeditiously provide the required HMMWV refurbishment capability. However, prior to the work being added to Task Order 1, numerous incidents of poor contractor performance were documented. We found that from October 2005 through April 2006, 8 notices describing poor performance 18 GAO 07-144. Page 15 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics were issued to the contractor. Some of the poor performance concerns mentioned in the notices follow: • Equipment status is not being updated in the reporting system. As a result, the maintenance battalion operational readiness reports are inaccurate and erroneous data are being reported to the Department of the Army. • Equipment is not being inspected in accordance with Army standards specified in Task Order 1 and initial technical inspections are not being conducted within the timeframe specified in the task order. • Contractor quality control inspections performed before equipment is presented to the government are inadequate and are not identifying critical maintenance faults. • Sensitive items are improperly accounted for. Additionally, in a letter dated March 15, 2006, the Army contracting officer notified the contractor of numerous areas of concern. The letter stated that asset management was ineffective to the point that the battalion’s ability to report readiness and determine when assets would be ready was impaired, maintenance could take significantly less time if thorough equipment assessments were performed, and equipment was consistently rejected because of inadequate quality control. The letter also stated that the Army felt that the contractor’s personnel staffing was insufficient to achieve all missions, as only 89 percent of the personnel that the contractor proposed to execute the contract requirements were on-hand for option year 1. More specifically, the letter stated that only 36 percent of the required personnel were on hand to perform the priority mission of preparing the Heavy Brigade Combat Team although funding had been placed on the contract for the mission. In addition, the Tire Assembly and Repair Program and Add-on Armor missions had only 41 percent and 45 percent of the required personnel on hand, respectively, despite being funded. We asked the Army contracting officer with overall responsibility for the contract why such a major mission was added to the contract, given the battalion’s concerns with the contractor’s performance. The Army official responded that the battalion did not raise concerns regarding the contractor’s capability to meet the requirements and there was confidence that the work was being placed with a contractor that had a good history of performance in theater. The official stated that while a letter citing concerns with the contractor’s ability to ramp up to full personnel strength and its quality control processes was issued, the Army believed the contractor was fully engaged in correcting the issues. Battalion quality assurance officials told us that all information regarding contractor performance is not always provided to the contracting officer. According to the Army’s problem resolution process, all corrective action requests should be sent to the contracting officer, but this was not being done according to battalion quality assurance officials. In some situations, the quality assurance officials wait until they have issued two or three requests related to the same area before they send the information to the contracting officer. Following this procedure could result in some corrective action requests not reaching the contracting officer. Additionally, some battalion officials said that they do not write as many corrective action requests as Page 16 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics are needed because they would spend most of their time writing them because of the repeated poor performance. Battalion’s Contract Management Oversight Team Is Inadequately Staffed According to Army officials, the battalion’s contract management oversight team is inadequately staffed to effectively oversee Task Order 1 in Kuwait and the battalion is concerned about its ability to administer cost plus award-fee provisions. We have previously reported on the need to have an adequate number of oversight personnel to ensure the effective and efficient use of contractors and the continued shortage of contract oversight personnel in deployed locations. Oversight personnel are responsible for performing the various tasks needed to monitor contractor performance, document results of inspections, analyze available inspection data, assess overall contractor performance, and evaluate the contractor’s performance when considering awarding additional work to the contractor. The battalion uses both military and civilian personnel to provide contract oversight. Battalion officials told us that there were not enough trained oversight personnel to effectively oversee and manage the maintenance contract in Kuwait. At the time we visited the battalion in April 2007, four oversight personnel positions were vacant and were still vacant as of September 2007. The vacancies included those for two military quality assurance inspectors and two civilian positions–a quality assurance specialist and a property administrator. Command officials were unsure why the military quality assurance positions had not been filled and told us that the vacant civilian positions were advertised but the command had not been able to fill the positions with qualified candidates. An administrative contracting officer told us that the quality assurance specialist position was filled for a short time in December 2006; however, the person was deemed unqualified and was assigned to another position. The quality assurance specialist is responsible for such activities as performing analysis of quality processes and procedures, tracking and coordinating training for quality assurance personnel, updating quality assurance surveillance plans, and ensuring productive interaction between Army and contractor quality personnel. Additionally, the battalion has been without a property administrator since the end of 2006, even though both the battalion and the Army Sustainment Command have identified issues with the contractor’s accountability for government furnished equipment. According to DOD’s Manual for the Performance of Contract Property Administration, property administrator responsibilities include administering the contract clauses related to government property in the possession of the contractor, developing and applying a property systems analysis program to assess the effectiveness of contractor government property management systems, and evaluating the contractor’s property management system and recommending disapproval where the system creates an unacceptable risk of loss, damage, or destruction of property. We found that some property administrator duties, such as approving contractor acquisition of items, were being performed by an administrative contracting officer; however, other important duties were not being performed. In March 2007, a team from the Army Sustainment Command’s Office of Internal Review and Audit Compliance conducted a review of government-furnished property accountability in Kuwait and identified areas for improvement in property accountability. For example, the team found that while required property accountability reports were prepared by the contractor, they were not being provided Page 17 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics to the Army nor did the Army request the reports. After reviewing one such report, the evaluation team questioned its accuracy. It found that the contractor was reporting a total of $2.4 million in government-furnished property; however, the value of two of the eight property listings reviewed totaled more than $2 million. Without adequate oversight of government property, the Army cannot be certain that duplicate supplies have not been ordered, government property is not misplaced or misused, and property in the possession of the contractor is being efficiently, economically, and uniformly managed. In addition to the two vacant quality assurance inspector positions mentioned above, Army officials also told us that additional quality assurance inspectors were also needed. The officials explained that three quality assurance inspector positions were removed from the Army’s authorized battalion organizational structure; however, the officials were not sure why the positions were removed because they believe the need still exists for the inspectors. According to battalion officials, vacant and reduced inspector and analyst positions mean that surveillance is not being performed sufficiently in some areas and the Army is less able to perform data analyses, identify trends in contractor performance, and improve quality processes. In some instances when contract administration and management positions cannot be filled permanently, the Army fills these positions temporarily. For example, the Army filled a vacant administrative contracting officer’s position in Qatar with an Army reservist called to active duty to fill the position for a specific period–2 months. In Kuwait, the battalion tried to fill the vacant positions temporarily but was unsuccessful. According to the battalion, it solicited for volunteers to fill the critical positions in Kuwait with deployments up to 179 days and requested volunteers from the Army Reserve and Guard. In addition, a relocation incentive was requested and approved for the critical property manager and quality assurance specialist positions. Also, the battalion said that it offered off-post housing to some Army civilian applicants and augmented military requirements with the mobilization of the U.S. Army Reserve Multi-Functional Support Command. As an alternative to providing its own contract administrative and oversight staff, the Army could have delegated the administrative responsibilities for Task Order 1 to the Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA). DCMA is a combat support agency tasked with providing contract administration support for contingency contracts like the GMASS contract and task orders at the request of the contracting officer. Depending on the delegation from the contracting officer, DCMA contract administrative personnel can provide a number of contract administrative services. For example, DCMA can assume responsibility for performing property administration, provide quality assurance specialists and supervise contracting officers’ representatives, monitor and evaluate technical performance, and review and approve purchase requests. In addition, DCMA administrative contracting officers may be given authority to negotiate certain price adjustments. Battalion officials also expressed concern that the battalion’s current staffing levels will make the potential transition from a cost plus fixed-fee to a cost plus award-fee structure for maintenance and supply services difficult. According to the GMASS indefinite delivery/indefinite-quantity contract, the Army envisioned transitioning to a cost plus award-fee structure in option year two for maintenance and supply services, Page 18 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics although the government reserved the right to change the contract line item structure. According to the contracting officer, the Army initially chose not to move to an award fee because the battalion did not believe it had the staff to properly administer the contract. We have previously reported that the development and administration of cost plus award-fee contracts involve substantially more effort over the life of a contract than do cost plus fixed-fee contracts.19 For award-fee contracts, DOD personnel (usually members of an award-fee evaluation board20) conduct periodic—typically semiannual—evaluations of the contractor’s performance against specified criteria in an award-fee plan and recommend the amount of fee to be paid. The Army contracting office is considering transitioning the major elements of option year 3 (including maintenance and supply services) from a cost plus fixed-fee structure to a cost plus award-fee structure, beginning January 1, 2008. However, according to battalion officials, they will not be adequately organized and staffed to properly administer award-fee structured provisions until about April 2008. Battalion officials stated that a new battalion commander took command on August 1, 2007, and as a part of his new role, he is reviewing the battalion’s organization and suggesting changes to better align the battalion to provide adequate contractor oversight and properly administer an award-fee contract. They stated that it would take some time before these changes would be in place and personnel are properly trained to take the actions needed to monitor contractor performance and assist in making award-fee decisions. Without adequate staff to monitor and accurately document contractor performance, analyze data gathered, and provide meaningful input to the award-fee board, it will be difficult for the Army to effectively administer an award-fee contract beginning in January 2008. Conclusions The Army has not taken sufficient actions to ensure quality contractor maintenance and efficient contract oversight. Given the poor performance by the contractor, adequate and well-documented surveillance, along with necessary corrective actions, are essential to improving the quality of work by the contractor. Poor performance by the contractor and inadequate Army oversight have resulted in expenditure of additional funds with less-than-expected results, additional cost to repair items already presented to the Army as meeting established standards, and may have resulted in delays in providing assets to deployed units. Without sufficient oversight of contractor performance, the Army cannot ensure that operation and maintenance funds for vehicle maintenance are being used cost effectively. Moving to a cost plus award-fee structure for certain elements of option year 3 will provide more risk to the contractor, potentially resulting in improved performance. However, without adequate Army oversight personnel and contractor performance data to make awardfee decisions, the Army cannot accurately determine whether the contractor should receive an award, and if so, how much. Without aggressive action on the part of the Army, the problems highlighted in this report will continue. 19 GAO NASA Procurement: Use of Award Fees for Achieving Program Outcomes Should Be Improved. GAO-07- 58 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 17, 2007). 20 Award-fee evaluation board members may include personnel from key organizations knowledgeable about the award-fee evaluation areas, such as engineering, logistics, program management, contracting, quality assurance, legal, and financial management; personnel from user organizations; and personnel from cognizant contract administration offices. Page 19 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics Recommendations for Executive Action We are making five recommendations in this report. We recommend that the Secretary of Defense direct the Secretary of the Army to review and evaluate the Army’s procedures for managing and overseeing the GMASS task order in Kuwait and take the necessary actions to improve contract management. We also recommend that the Army develop a strategy to implement its current quality assurance and maintenance management oversight plans to ensure that • all deficiencies are documented in the Army’s quality assurance database without affecting the mission • contractor data are analyzed to improve contractor performance, and • all information on contractor performance is provided to the contracting officer. In addition, we recommend that the Army: • take steps to fill vacant oversight positions with personnel who have the appropriate knowledge and skills, and • develop a plan to allow the proper administration of the cost plus award-fee structure for maintenance and supply services. Furthermore, we recommend that the Army consider delegating some additional oversight responsibilities to DCMA to meet some of the current contract management and oversight personnel shortfalls. Agency Comments and our Evaluation In commenting on a draft of this report, DOD concurred with our recommendations and discussed proposed implementation actions to be taken by the Army. In responding to our recommendations for the Army to improve contract management and develop a plan to allow for the proper administration of a cost plus award-fee contract, DOD stated that the Army is reviewing the contract to determine the best contract type to improve contract management. Assuming the Army is adequately organized and staffed to administer the contract type selected, we believe that this action could allow the Army to identify and determine the best procedures for managing and overseeing this contract. In response to our recommendation that the Army develop a strategy to implement its current quality assurance and maintenance management oversight plans, DOD said the Army Field Support Battalion-Kuwait has developed a multi-pronged strategy to implement and/or improve quality assurance and maintenance management oversight. We believe effective implementation of the strategy should address our recommendation. In response to our recommendation that steps be taken to fill vacant oversight positions, DOD said that the Army continues to exercise several recruiting authorities to entice qualified candidates to fill critical vacancies. However, the Army stated that filling the critical quality assurance specialist position continues to be difficult. According to the Army, in December 2007, both the first and second choice to fill the position declined the offer. The position is being announced again and the Army is working to streamline the recruit and fill process and will continue to pursue filling this critical position. Given the difficulties of filling deployed positions, we believe these actions are reasonable and should help to identify someone to fill this position. In response to our recommendation for the Army to consider delegating some additional oversight responsibilities to DCMA, DOD stated that delegating additional oversight Page 20 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics responsibilities to DCMA is predicated on the ability of the DCMA to support the contract. We understand that DCMA would play a major role in the decision to delegate additional oversight responsibility to them. DOD’s comments are reprinted in enclosure II. ____________ We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense and the Secretary of the Army. We will also make copies available to others upon request. In addition, this report will be available at no charge on the GAO Web site at http://www.gao.gov. If you or your staff has questions, please contact me at (202) 512-8365 or solisw@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. Key contributors to this report are listed in enclosure III. William M. Solis Director, Defense Capabilities and Management Enclosures - 3 Page 21 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics List of Committees The Honorable Carl Levin Chairman The Honorable John McCain Ranking Member Committee on Armed Services United States Senate The Honorable Daniel K. Inouye Chairman The Honorable Ted Stevens Ranking Member Subcommittee on Defense Committee on Appropriations United States Senate The Honorable Ike Skelton Chairman The Honorable Duncan L. Hunter Ranking Member Committee on Armed Services House of Representatives The Honorable John P. Murtha Chairman The Honorable C. W. Bill Young Ranking Member Subcommittee on Defense Committee on Appropriations House of Representatives Page 22 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics Enclosure I: Scope and Methodology To evaluate the contractor’s performance of maintenance and supply services under the Army’s Global Maintenance and Supply Services task order, Task Order 1, we interviewed Army contracting officials at the Army Sustainment Command in Rock Island, Illinois; interviewed Army officials of the 401st Army Field Support Battalion at Camp Arifjan, Kuwait as well as contractor representatives responsible for the management of Task Order 1; reviewed various Army and contractor documents related to contractor execution; and observed the contractor’s maintenance processes. We reviewed all records of quality assurance inspections conducted from November 2005 through May 2007 for equipment maintained by the contractor. Subsequently, we analyzed the inspection result data for selected equipment types inspected from July 2006 through May 2007 to determine the percentage of items failing inspection. We subjectively selected equipment types that were commonly repaired by the contractor, were perceived to be critical to the fight in Iraq and Afghanistan, and were among the battalion’s highest repair priorities. Although the Army has not documented all deficiencies that would indicate failed inspections and be recorded in the database, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of our review. We took several actions to assess the reliability of the data. Specifically, we reviewed battalion guidance and procedures for how inspections should be conducted and documented, interviewed several quality assurance inspectors to determine how they conducted and documented inspections, observed the conduct of some quality assurance inspections, and observed the documentation of inspection results. We also met with representatives of the contractor, reviewed quality data provided by the contractor, and discussed our report’s findings, conclusions, and recommendations with contractor representatives. To determine the extent to which the Army’s quality assurance and contract management activities implement key principles of quality assurance and contract management regulations, we met with contracting and quality assurance officials at Camp Arifjan, Kuwait, and Rock Island, Illinois, and reviewed oversight and surveillance plans and inspection records. We reviewed a variety of quality assurance and contract management regulations and guidance, including the Army Quality Program regulation and the Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement. In addition, we spoke with representatives of the contractor and reviewed data provided by the contractor. We also observed physical inspections of four pieces of equipment presented to the Army while we were at Camp Arifjan and analyzed Army-provided data on oversight and surveillance. To determine if the battalion was adequately staffed to perform oversight activities, we reviewed battalion staffing documents and spoke with battalion oversight and command officials as well as officials from the Army Sustainment Command. In addition, we reviewed Department of Defense and Army guidance and regulations regarding contract oversight and management. We conducted this performance audit from March 2007 through December 2007 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. Page 23 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics Enclosure II: Comments from the Department of Defense Page 24 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics Page 25 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics Page 26 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics Page 27 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics Enclosure III: GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments GAO Contact William M. Solis, (202) 512-8365 or solisw@gao.gov Acknowledgments In addition to the contact named above, Carole Coffey, Assistant Director; Sarah Baker; Renee Brown; Janine Cantin; Ronald La Due Lake; Katherine Lenane; and Connie W. Sawyer, Jr. made key contributions to this report. (351106) Page 28 GAO-08-316R Defense Logistics This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately. GAO’s Mission The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability. Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through GAO’s Web site (www.gao.gov). Each weekday, GAO posts newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence on its Web site. To have GAO e-mail you a list of newly posted products every afternoon, go to www.gao.gov and select “E-mail Updates.” Order by Mail or Phone The first copy of each printed report is free. Additional copies are $2 each. A check or money order should be made out to the Superintendent of Documents. GAO also accepts VISA and Mastercard. Orders for 100 or more copies mailed to a single address are discounted 25 percent. Orders should be sent to: U.S. Government Accountability Office 441 G Street NW, Room LM Washington, DC 20548 To order by Phone: Voice: TDD: Fax: (202) 512-6000 (202) 512-2537 (202) 512-6061 Contact: To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs Web site: www.gao.gov/fraudnet/fraudnet.htm E-mail: fraudnet@gao.gov Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7470 Congressional Relations Gloria Jarmon, Managing Director, jarmong@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400 U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125 Washington, DC 20548 Public Affairs Chuck Young, Managing Director, youngc1@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800 U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149 Washington, DC 20548 PRINTED ON RECYCLED PAPER