GAO DEFENSE CONTRACTING Additional Personal

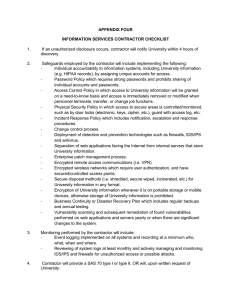

advertisement