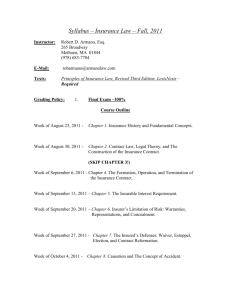

DEFENSE BASE ACT INSURANCE State Department

advertisement