GAO PEACE OPERATIONS Heavy Use of Key Capabilities May Affect

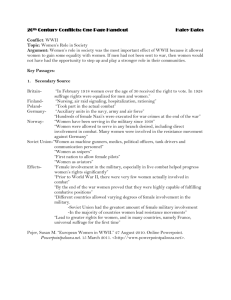

advertisement