4.0 DESCRIPTION OF BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES

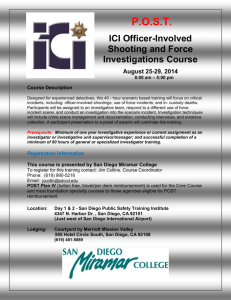

advertisement