CRS Report for Congress China-U.S. Relations: Current Issues for the 108 Congress

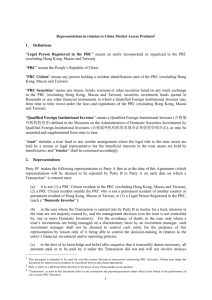

advertisement