STRATEGIC STUDIES INSTITUTE

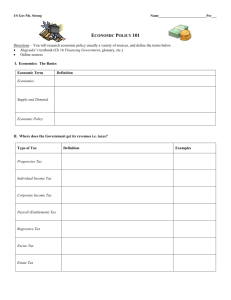

advertisement