Document 11049565

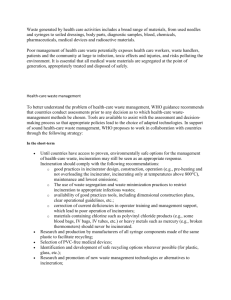

advertisement