ALLIANCES AND AMERICAN NATIONAL SECURITY Elizabeth Sherwood-Randall October 2006

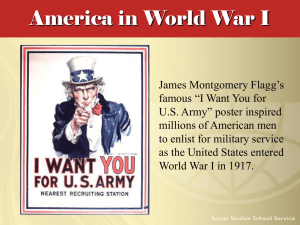

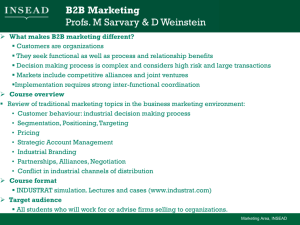

advertisement