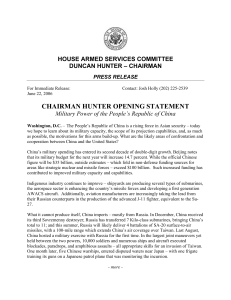

string of Pearls: meeting the challenge of china’s rising Power

advertisement