Document 11045688

advertisement

HD28

DBWEf

.M414

f3

ALFRED

P.

WORKING PAPER

SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT

The Imperfect Legitimation of Inequality

in Internal

Labor Markets

Maureen Scully

Assistant Professor of Management

MTT Sloan

School, E52-568

Cambridge,

MA

02139

617-253-5070

Working Paper 3520-93-BPS

January. 1993

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

50 MEMORIAL DRIVE

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 02139

i

The Imperfect Legitimation of Inequality

in Internal

Labor Markets

Maureen Scully

Assistant Professor of Management

MTT Sloan

School. E52-568

Cambridge.

MA

02139

617-253-5070

Working Paper 3520-93-BPS

January. 1993

1

C (r

!

f

>.

M.I.T.

LIBRARIES

The Imperfect Legitimation

of Inequality in Internal

This study addresses whether employees believe

Labor Markets

advancement

that

is

based on merit

in

two

non-unioni/.ed, high technology companies that have formal merit-based performance evaluation and

One

promotion procedures.

reason companies use the language and logic of meritocracy

encourage employees to work harder

in the

expectation of greater rewards.

based procedures -indeed their very intent according to

That

that inequality is legitimated.

that inequality

is

based

fairly

is,

in merit.

to

implication of merit-

Edwards, 1979) -

critical theorists (e.g.,

employees may believe

on differences

An

is

that merit counts for

Employees' shared belief

is

advancement and

in the rationality

of

"impersonal," merit-based governance procedures been invoked by institutional economists to explain

reduced turnover in internal labor markets

(e.g.,

Doeringer

&

Piore,

explain employee cooptation and the general lack of employee dissent

1971) and by sociologists to

(e.g.,

Edwards, 1979).

paper theoretically challenges and empirically investigates this often-invoked notion.

that beliefs about merit vary

by how employees

fare in

1

This

argue, instead,

an organization's advancement contest.

Those

in lower positions, or those with lower mobility rates, or both are less likely to believe that merit

counts in their firm, whether from a savvy born of personal experience or from a need to make

enhancing attributions.

In

some

fashion, they cope with the

judgment implicitly

pertbrmers in a putative meritocracy and deny the claims that merit counts.

argument

that the less successful

doubt the role of merit

is

Upon

hardly surprising

self-

upon lower

cast

brief reflection, an

However,

this

simple

alternative

view has been theoretically overshadowed by overdetermined accounts of socialization and

cooptation.

This view has not been empirically investigated, specifically in a workplace setting where

questions can be addressed about whether

dimensions of

stratification, that correlates

it

is

position or

upward mobility, quite different

with the extent of belief in merit.

Finally, this

view has not

been incorporated into new kinds of economic and sociological theories about the employment

relationship,,

which might look

different they

if

employees do not believe the legitimating claims

employment

relationship.

took seriously the possibility that a

that are

fair

number of

supposed to be the ideological glue of the

The term "meritCKracy" was

a satirical invention of

negative consequences of a rigidly ment-based society.

soberly, to late capitalist systems of status

from class-based or aristocratic systems,

and reward

in

this study,

human

capital variables that

argue that

it is

has since been applied,

somewhat more

allocation, usually to distinguish

There

is

them favorably

a long sociological tradition,

of examining whether variance in occupations and incomes

merits or to class background.

of the hidden

in his fable

which family origin and unearned advantages determine

occupations and incomes (Bell, 1972, 1976).

backdrop to

It

Young (1958)

Merit variables usually include education,

economists would use in wage equations.

difficult to find "pure" merit variables, since

test scores,

is

which

is

the

attnbutable to

and the kinds of

Jencks and colleagues (1972)

most of the measurable ones are already

influenced by privileged family backgrounds and variables like marginal productivity are too hard to

measure.

In the sociological equations, the merit variables are contrasted to class variables, like

parents' occupations

liberal

and family income, and also

agenda of demonstrating

policies are needed.

Alongside

that class, race,

show.

like hard

&

sex), often with the

conducted surveys to see

to be important in determining occupation

Beliefs are of interest, in addition to, and even irrespective of,

In general, national studies of beliefs (e.g.,

Schlozman

and

and sex continue to count too much and correctives

this descriptive research, sociologists also

what variables individuals believed

United States.

to ascriptive variables (race

Huber

&

and income

in the

what the equations

Form, 973; Kluegel

&

Smith, 1986;

Verba, 1978) found strong endorsement (about two-thirds of respondents) that merits

work and

ability determine individual outcomes. Theoretical attention

was directed

to the

formidable effectiveness of meritocratic ideology as a legitimating ideology.

Researchers studying status and reward allocation have turned their attention to the features of

an organization that may help explain why individuals with similar

traits realize different returns to

For example, the structure of job openings affects whether individuals are promoted

those

traits.

(e.g.,

Mittman, 1986; Stewman

&

Konda, 1984; White, 1970). The study of what individuals believe

to be the causes of inequality should similarly shift

from the national

level to the organizational level.

National level studies of beliefs about inequality, despite giving the overall impression of consensus,

do find variance

in beliefs

about the role of merit, as

Mann

(1970) suggests. Moreover, they find

variance within the upper-class, within the middle class, and within the working class.

variance

may

arise because individuals have dilTercnt local experiences in the

their organizations.

to technician, but

Some

of this

advancement contest

in

For example, some members of the working class are promoted from assembler

some

are not; the former

may

be stronger believers in the role of merit.

Including

information about the individual's experience of being promoted or not, by conducting a study of

beliefs within

an organizational context, might help explain variance

be unaccounted for in national surveys.

This study begins

this

in beliefs that

important

would otherwise

move from

the national to

the organizational level in the area of beliefs about meritocracy.

Certainly there have been numerous studies of individual attitudes that have been conducted

Studies of satisfaction and

within organizations.

satisfaction with promotions

and willingness to work

commitment often include questions about

hard.

However, these studies

treat individuals

views about hard work and rewards as neutral, atomistic calculations, relevant within the firm as a

motivation problem.

They do

not connect with the broader stream of research on meritocracy.

The

broader social and political implications of employees' beliefs about whether merits are rewarded

must be taken into account and give a much greater significance to findings about employees'

These findings reveal not just the likelihood of employees' exerting

about meritocratic claims.

but

beliefs

more fundamentally, they

reveal the extent to

which a firm derives some normative legitimacy

from practices rooted in the widespread cultural appeals to meritocracy

in the society at large.

how

This

As

such, findings that

they are doing in the firm suggest not only that

new procedures may

study examines employees' beliefs about merit from this standpoint.

employees' beliefs vary by

effort,

have to be explored by the firm to bring people normatively on board, as argued from the procedural

justice perspective.

They

also suggest that the sense-making schemes that individuals

employ

in

committing to a firm and coping with inequality either leave the firm vulnerable to legitimacy

challenges or must be understood as involving more complexity and ambivalence than binary

accounts of legitimation

One

/

delegitimation have tended to allow.

possible finding

is

that there will be very

little

variance in employees' beliefs about merit.

People in the higher positions in organizations should believe that merit counts, since they

may

interpret their

own

experience as one of meritocratic ascent and since

bolsters their position; that

it

the people in the highest positions should promulgate self-reflective and even self-serving ideologies

has been argued for

The

some time

sociological literature

of class" (Sennett

&

in social theory (e.g., Mar.x

on the legitimation of

Cobb, 1972)

is

&

Engels, 1978: 64; Weber, 1971:956).

inequality^ suggests that

As Mann

those

whose energies and

The

literature

argues, inequality

abilities

injuries

the tendency of people in lower positions to go along with this

dominant view, accept meritocratic ideology, and blame themselves and

lower position.

one of the "hidden

deserve

on organizational

it,

is

legitimated

failures

when people

their inferior merits for their

believe that "success

have only themselves to blame"

comes

to

(1970:427).

and commitment suggests that employees may be

culture

socialized to believe the frequent articulations of the meritocratic ideal in organizations that use

Organizational culture research documents corporate versions of the rags-

merit-based procedures.

to-riches story (e.g., Martin, Sitkin,

for the choice of

who

is

Feldman

&

Hatch, 1983).

promoted or not emphasize individual

structural constraints identified

by researchers mentioned above,

the rationality of the promotion system, sustain

its

o,

,

Mt^YPr

^

Rowan, 1978)

Alternatively,

work on

in turn.

little

al.,

is

by management

and merits, rather than the

in order to

1982).

Taken

maintain the "myth" of

Theories of institutionalization

who would

take for granted

together, organizational theories can

variance in beliefs about merit should be found.

recent sociological writing on the experience of

attributions point to the likeliness of finding variance.

There

traits

also add to a portrait of employees

practices like merit-based performance evaluations.

easily build a case that

rationales given

motivational potential, and bolster the authority of

those chosen by this system (Salancik, 1977; Pondy et

(f

The

work and

These two

social psychological

literatures are considered

a growing body of research that describes a working class whose

members

are aware

iDella Fave (1980:955) defines legitimation as follows, drawing on definitions employed in previous

inequality (Alves

Rossi, 1978; Jasso

Rossi, 1980; Rainwater, 1974): "Legitimation refers

to a belief on the part of a large majority of the populace that institutionalized inequality in the

distribution of primary resources (Rawls, 1971) - such as power, wealth, and prestige - is essentially

right and reasonable." The claim that inequality is meritocratic, and particularly that hard work and

ability lead to success, is one specific contemporary form of the legitimation of inequality (e.g.,

Althusser, 1969; Giddens, 1973; Huber

Engels, 1846; Miliband,

Form, 1973; Mann, 1971; Marx

1969; Mills, 1969; Schlozman

Verba. 1978).

work on

&

&

&

&

&

of their

own

own

interests

and not easily coopted by a dominant ideology

Some examples

experiences.

on experience-based differences

in

Mann

include

that

is

not corroborated by their

(1970) on dissensus, Larkwood and others (1975)

working class images of society, Willis (1981) on the dissident

values of British working class youths, Scully (1982) on the intact self-esteem of high schoolers

how

sorted into the lowest tracks, Sabel (1982) on

working class

the

struggles over the division of labor in the workplace,

is

well aware of

role in

its

MacLeod (1984) on how Boston

power

area youths do

not necessarily believe claims that hard work leads to success, Scott (1985) on everyday forms of

ideological struggles by the peasantry against the powerful,

upward progressions does not apply

careers as orderly

Thomas (1989) on how

research on

to the lived experience of blue collar workers,

and Gamson (forthcoming) on the complexity and nuance, which should not be surprising,

belief systems of

The

members of

social psychological literature

make self-enhancing

successful people

successful people

(e.g.,

the working class

Seligman

make

et al.,

on issues such

attributions

1972).

al.,

common

as ability or hard

pattern

work) and

whereby individuals

1991).

&

traits),

The "fundamental

own

attribution error" (Jones

(Murphy

&

successes to internal factors (such

their failures to external causes (such as structural constraints or luck)

&

Sims, 1985; Mitchell, Green

&

this long-accepted social

Wood, 1981,

&

Cleveland,

psychological style of sense-making

understanding the legitimation of inequality have not been drawn by social psychologists.

implication

is

that meritocratic ideology

successful inasmuch as

cognitions.

it

&

Cleveland, 1991),

Ross, 1975) can be applied to the performance evaluation process (Murphy

The implication of

while less

appeal to external constraints and biases)

attribute their

Research on self-serving biases in attribution (Gioia

Miller

action.

failure predicts that

appeal to internal

(e.g.,

Nisbett, 1971), though no longer regarded as universal or fundamental

describes a

and affirmative

on attributions about success and

self- protecting attributions (e.g.,

1979; Weiner et

as inequality

in the

depends upon

is

their

likely to fail

for

The

in legitimating inequality to the less

blaming themselves and not employing self-protecting

Hypotheses

Sociologists have pointed to multiple and competing systems of stratification within and

outside organizations (Granovetter

&

Organizations have a distribution of positions, of

Tilly, 1986)

performance evaluations, of degree of return on human

considers whether

how an

relates to their beliefs

Beliefs about

much

individual

about

is

how much

how much

doing in any or

all

rates.

This study

of these various local mobility contests

merit counts.

how

merit counts are operational i zed by by having employees rate

(on a 7-point scale) they believe each of five items counts for advancement: hard work, ability,

performance, privilege, and luck.

These items

what individuals believe does and ought to

Coleman

&

and of mobility

capital,

&

Rainwater, 1978; Huber

&

An employee who

Verba, 1978).

are considered in

&

believes that the firm

work, and performance as very important determinants of

coming from a privileged background and luck

relationships

is

the

same

work may be

United States

of

(e.g.,

Smith, 1986; Mann, 1970; Schlozman

is

would

meritocratic

who

rate ability, hard

gets ahead in the firm,

Though

as not important.

The items

are different

a variable input, and performance

form a conceptually nor empirically sound

makes sense not

in the

level studies

and

rate

the expected pattern of

for the five variables in the hypotheses below, they are treated as five

separate dependent variables in this study.

fixed input, hard

and income

affect occupation

Form, 1973; Kluegel

numerous national

scale.

is

enough

(e.g., ability

may

be a

an output) that they might not

In addition, as a first study of these variables,

more "open" look

to aggregate variables, but to take a

at the

it

data and uncover

unexpected differences (Bailyn, 1977).

Hypotheses

human

capital,

1

to

4

relate success in

and mobility to

terms of position, performance evaluation, return on

beliefs about merit.

Hypotheses 5 to 8 address other aspects of

employee's experience in the advancement contest: their recent

lateral mobility,

whether they have

crossed a "class boundary" from hourly to salaried, whether they are a manager, and their tenure.

Hypotheses 9 and 10 consider employees perceptions of

a possible sex difference.

their

advancement, and Hypothesis

1 1

posits

Success in the firm's advancement contests

1.

Position in

tlie

organizational hierarchy. Position

of success in the firm, even

if

may

represent the ultimate attamment

The

best

to the highest positions

A

individuals socially construct alternative and local indicators.

rewards and the largest allocation of scarce societal resources attach

person exports the rewards of organizational position - from a paycheck to social esteem - into the

Locally constructed indicators of success

larger society.

(e.g., best

assembler) do not export as well.-

Job ladders and bureaucratic hierarchies have long implied a ranking of employees by merit, such

that the

most meritorious employees are

connotation,

it

is

at the top

self-enhancing for people in

role of merit

luck).

and

Similarly,

cite the role

it

is

In a world

where rank has

this

higher positions to believe in meritocracy and to

attribute their position to their merit (and also, to

background or

(Weber, 1946a).

deny the

role of non-merit factors,

such as class

self-enhancing for people in lower positions to downplay the

of non-merit factors.

Hypothesis 1. The higher the employee's position in the firm, the more strongly he or she believes:

o that hard work counts for getting ahead,

o that abihty counts for getting ahead,

o that performance counts for getting ahead.

o that coming from a privileged background does not count for getting ahead,

o that luck does not count for getting ahead.

If beliefs

about meritocracy do

the organization and a

map

demand from people

onto position, one might expect a crisis of legitimacy in

in

lower positions that people in higher positions turn

over some of their "unearned" rewards. Variance in beliefs by position looks like a class-stratified

belief system.

ladders,

may

mobility, and

However,

internal labor markets, particularly narrowly defined jobs arranged in

constrain people's social comparisons, focus people's aspirations on local upward

mask

vast differences in position and attendant rewards, thus preventing (intentionally

or incidentally) a class -stratified belief system and the discontent

it

might engender.

^Discussions of inequality take many forms, but at their basis, the interesting issue is the gap between

those in the highest and lowest positions. It is good not to lose sight of the fact that the highest

position is the highest reward, even in the process of discussing how participants in the social system

may be satisfied by other, compensatory successes, like climbing lower rungs of the ladder or

receivina good performance evaluation within their job grade.

8

2.

Upward

Absolute position may not matter as

mobility.

much

to individuals as their

success or failure in improving their position in the hierarchy via upward mobility.

organizations, their mobility rate

their absolute position.

and

may

The words of one employee

are but

where you're going

The data

success in the competition for increased rewards

an internal labor market where insiders compete to

levels.

Methods

First, there is

and controls for differences

higher rate than a slow, steady incumbent).

employee has advanced.

Rates of

company and may depend

in part

a

comparison referents

Hypothesis 2.

o that

o that

o that

o that

o that

3.

in their

to be

more

is

higher

ways

rate

which

in

(number of

fast-moving newcomer has a

it

meanings

may

of the

in different areas

be worth looking at the absolute

be more attuned to their mobility rate

immediate occupational

mean and

three

simply the absolute number of levels the

so

may

show

which captures the speed with which

different

arise,

Third, people

(to correct for the

normed measure proves

Second, there

movement may have

rate.

section,

in tenure (so that a

on when openings

ascent without the correction for

can be standardized

at

not where you

"It's

an employee's mobility

levels of the hierarchy transcended divided by years of tenure),

rate

openings

that counts."

upward mobility might be operationalized.

relative to social

fill

interviewed for this study typify this view:

I

for this study, discussed below in the

the person advances

in

be the more salient reward in the status attainment contest than

Movement upward connotes

status, particularly in

For individuals

area.

Each person's mobility

standard deviation of their group) to see

if

such

useful for understanding variance in beliefs about merit.

The greater an employee's upward mobility, the more strongly he or she believes:

hard work counts for getting ahead,

ability counts for getting ahead,

performance counts for getting ahead.

coming from a privileged background does not count for getting ahead,

luck does not count for getting ahead.

Relative return on education and tenure. This variable

failure in terms of specific social

education, their starting

human

comparison

referents.

capital, to the firm.^

is

another indicator of success or

Individuals bring different amounts of

Individuals

may

not expect to do as well as those

^Other studies have addressed whether education itself is distributed meritocratically or not. The firm

inherits already educated individuals, and personnel managers sometimes take pains to argue that

they and the firm are not in a position to correct for past inequalities of opportunity.

who

but

more

bring

do expect

to

capital, in the

do

as well as similar others,

become Vice

not expect to

form of education or years of experience,

President (despite popular Horatio Alger stories about such

he or she should expect to become Lead Technician

have done

so.

on education and tenure

believe less strongly that

Hypothesis

advancement

contest,

may

lor example, a person with a high school diploma

rises), but

a return

to the

if

meteoric

others with a high school degree

that is relatively too

low should make an individual

ment guides advancement.

The greater an employee's return on education and tenure, the more strongly he or she

3.

believes:

o

o

a

o

o

hard work counts for getting ahead.

that

that ability counts for getting ahead.

performance counts for getting ahead.

coming from a privileged background does not count for getting ahead.

luck does not count for getting ahead.

that

that

tliat

how

This measure comes closest to capturing individual's "actual" merits, but also reveals just

difficult

it

for lack of

4.

is

to

answer the question of whether the companies

good measures of

in this study "really are" meritocracies,

merit.

Performance evaluation. The performance evaluation process

individuals in the

same job area

like privilege

in a

may

and

way they may

latter

relate to

luck.

not

two variables

whether they attribute success

Employees know

know

what most directly

pits

against one another and assigns relative winners and losers.

Employees' sense of how well they are doing might be tightly tied

evaluation and

is

their

in the

to their recent

performance

firm to merit or to non-merit factors

performance evaluation (often a number from

their exact mobility rate or their relative return

are constructed by researchers), so

it

may prove

on human

to be the best

1

to 5)

capital (these

measure

for

understanding beliefs about merit.

Hypothesis 4.

she believes:

a that

o that

o that

o that

o that

The higher an employee's

last

performance evaluation rating, the more strongly he or

hard work counts for getting ahead.

ability counts for getting ahead.

performance counts for getting ahead.

coming from a privileged background does not count for getting ahead.

luck does not count for getting ahead.

10

other advancement experiences

in the

firm

Lateral moves (recent). Lateral moves can create a sense of movement, perhaps whether

5.

or not the individual

is

making

real

headway up the

vertical ladder of the organization.

(1987) found that job ladders represent idealized routes of movement, but in practice,

between ladders are as frequent and can improve career prospects.

the mobility variables discussed so

scale.

Recent

lateral

moves

far,

moves

Lateral

still

lateral

moves

are not captured in

which chart only movement up hierarchical

(within the past three years) are the ones that

DiPrete

levels of the

pay

hold the promise of

converting into upward mobility opportunities (whereas this promise for lateral moves of several

may have

years ago

expired).

5. The greater the number of lateral moves an employee has made(in

more strongly he or she should believe:

o that hard work counts for getting ahead.

Hypothesis

the past three

years), the

o tfiat ability counts for getting ahead.

o that performance counts for getting ahead.

o that coming from a privileged background does not count for getting ahead.

o that luck does not count for getting ahead.

Crossing a class boundary.

6.

Internal labor markets often have multiple ports of entry.

Hourly workers and salaried workers enter

bottom of the engineering

start at the

for hourly production

to salaried worker.

at different starting

ladder,

and technical workers.

which

It is

is

pay grades. For example, engineers

already higher than the top rung of the ladder

difficult for hourly

Essentially, they face a ceiling

on

their mobility prospects. DiPrete

(1988) found that crossing a boundary from the lower to upper

moment

significant

who have

in a career history

tiers

For those

crossed this particularly salient boundary, this single event, irrespective of other indicators

may

condition strongly their sense of success.

Hypothesis

6. If

an individual has crossed the boundary from hourly

more strongly:

o that hard work counts for

o

o

o

o

and Soule

of the civil service was a

and the greatest source of disadvantage for women.

of mobility,

believe

workers to cross the boundary

to salaried,

he or she should

getting ahead.

that ability counts for getting ahead.

that performance counts for getting ahead.

that coming from a privileged background does not count for getting ahead.

that luck does not count for getting ahead.

11

definitive aspect of being a

make

manager

a person defend the practice,

Following

Pfeffer's (1981)

organizational symbols,

more

Whether the employee

Being a manager.

7.

likely

a

manager might inlTuence

having to conduct performance evaluations, which might

mostly for the authority

it

confers (Dornbusch

argument, people in managerial positions

some of which symbolize

&

Scott, 19'

manage

in the organization

that the firm is meritocratic;

the

managers become

abilitv counts for getting ahead.

performance counts for getting ahead.

coming from a privileged background does not count for getting ahead,

luck does not count for getting ahead.

Predictions about the role of tenure in understanding beliefs

in the firm.

tinged by researchers' prior on whether firms tend to be meritocratic.

If

basically meritocratic, despite occasional, local deviations, then one

would predict

to see this pattern

tenure and belief that the firm

emerge

is

after longer tenure

meritocratic.

meritocratic, predictions about tenure

Conversely,

would stem from

one believes

if

one believes

a chronicle of

how

becomes disillusioned

of such deviations.

relationship between tenure and belief that the firm

is

that the firm is

that

that the firm

when seeing deviations from merit

at the repetition

may be

employees

and predict a positive relationship between

gives the firm the benefit of the doubt

this

A

Managers should believe more strongly:

hard work counts for getting ahead,

Tenure

would begin

beliefs

themselves to be persuaded by these symbols.

Hypothesis 7.

o that

o that

a that

o that

o that

8.

if

is

is

The

latter

second view, since reviews of performance evaluation practices suggest

Of

basically not

employee

criteria, but

initially

eventually

account suggests a negative

Hypothesis 8

meritocratic emerges.

firms to find and consistently use unbiased measures of merit.

the

is

it

is

is

based on

extremely difficult for

course, a third possibility

is

that

individual employees have different experiences of gradual confirmation or disconfirmation that

merit applies as they remain with a firm, and thus no significant effect in one direction or the other

emerges

for tenure.

Hypothesis 8. The longer an employee's tenure in the firm, the weaker his or her belief:

o that hard work counts for getting ahead.

a that ability counts for getting ahead,

o that performance counts for getting ahead.

o that coming from a privileged background does not count for getting ahead,

o that luck does not count for getting ahead.

12

Perceptions of advancement

9.

Perceived relative mobility.

mentioned, they

may

not

know

Individuals' actual mobility

their mobility rate or believe

it

is

measured above. However, as

something

to be

Their

different.

perceived advancement may, therefore, relate more strongly to their beliefs about merit.

Hypothesis

9.

The better an employee perceived his or her mobility

to be, the

more strongly he or she

believes:

o that hard work counts for getting ahead.

o that ability counts for getting ahead.

o that performance counts for getting ahead.

o that coming from a privileged background does not count for getting ahead.

o that luck does not count for getting ahead.

10.

Disappointment aiM>ut performance evaluation. Some employees who receive

performance evaluation

a meritocracy,

even

may

if it

accept that their

is

one

in

it

reflects their lesser merits

which they are doing

less well.

and believe

a

low

that the firm

is

Other employees may be

disappointed that their performance evaluation should have been higher.

This discrepancy

may

relate negatively to the belief that merit counts.

Hypothesis 10. The greater the discrepancy between the performance evaluation an employee felt he

or she deserved and the actual performance evaluation received {i.e., the greater the

disappointment), the weaker his or her belief:

o that hard work counts for getting ahead.

o that ability counts for getting ahead.

o that performance counts for getting ahead.

o that coming from a privileged background does not count for getting ahead.

o that luck does not count for getting ahead.

Demographics and controls

11. Sex.

The tendency

the socialization of girls and

to

make

women

self-enhancing attributions

suggests that

evaluations of them and to accept blame

Nelson,

&

Enna, 1978;

Dweck

&

when they

Goetz, 1978).

women

are

may

more

differ

by

women,

Research on

likely to internalize others'

receive poor ratings (e.g.,

Therefore,

sex.

Dweck, Davidson,

irrespective of position,

may

more likely to believe in meritocratic ideology, an exploratory prediction that this study examines.

Hypothesis 11. Female employees will believe more strongly:

o that hard work counts for getting ahead.

o that ability counts for getting ahead.

o that performance counts for getting ahead.

o that coming from a privileged background does not count for getting ahead.

o that luck does not count for getting ahead.

be

13

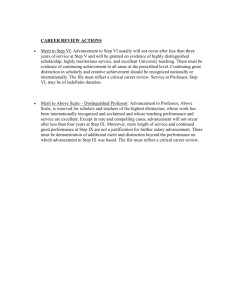

Occupational and firm controls.

individual le%

el

Table

1

This study examines mechanisms that work

and makes no a priori predictions about firm or occupation

(all

at

the

effects.

working paper) summarizes the hypotheses.

tables appear at the end of this

Method

Survey design

I

developed and administered a questionnaire to measure the preceding variables. The survey

includes attitudinal variables measured using 7-point Likert-type scales.'^ For the five dependent

variables, respondents

answered questions about how much the thought each item (hard work,

performance, privilege, and luck) counted for advancement

A

not count, 7=counts very much.

pretest, involving eight

four from one of the companies, indicated that wording

some of

the variance, since "does not count at all"

advancement was also measured using a 7-point

very much).

1

in the firm.

ability,

(The scale used was: l=does

respondents not from the companies and

as "does not count very

was perceived

much" truncated

to be the other endpoint.)

scale (l=have not

advanced

at all,

Perceived

7=have advanced

For the other "perception" variable, employees were asked what performance evaluation

they thought they deserved.

The other

employment

at the

variables were calculated from information each

history, including their

company,

the current year.

from

to 4).

most recent performance evaluation (l=low, 5=high),

starting position in the

mobility can be calculated.

They

The number of

From

their

start date

company, and current position, from which tenure and

also supplied the job

recent lateral

their starting

employee provided about

titles

they had for the three years preceding

moves was constructed from

and current positions,

I

this

information

(it

ranges

could calculated whether they had "crossed

'^Caution is certainly warranted in using ordinal variables as dependent variables, even though this

usage has a long history in the social sciences. I was concerned that coefficients might understate the

relationship, particularly of issue in interpreting whether position is not significant. Subsequent to the

analyses reported herein, I recoded the dependent variables (0= 1,23,4 and 1 = 5,6,7) and performed

logistic regressions. The pattern of results was the same, and position was not significant (nor was it

significant when position itself was recoded into fewer categories).

14

a class boundary" from hourly (non-exempt) to salaned (exempt);

passage was particularly prized

at these

Though employees supplied

etc.) are

my

interviews revealed that this

companies

the input data, the actual measures (of mobility, lateral

moves,

calculated by the researcher, and as such, these can be considered "quasi-objective" measures.

The inclusion of such measures

coefficients likely

mitigates concern about

when independent and dependent

variance

(i.e.,

inflated

variables are both attitudinal measures obtained

Common

from the same instrument) (Spector, 1987)

common method

method variance must be kept

in

mind,

however, for the relationship between perceived advancement and beliefs about merit (even though

these questions were asked several pages apart on the survey).

Selection of two companies

The study of employees'

beliefs about merit

is

most relevant

for

companies

that

have two

features of internal labor markets: merit-based promotion systems that are part of the governance

structure

and promotion from within. Promotion contests

most organizations" (Baker, Jensen

markets can use different

will

move up

criteria

&

"are used as the primary incentive device in

Murphy, 1988:600)

- such as

the organizational ladder^

for a

number of

merit, need, or seniority

-

reasons.

Internal labor

for the determination of

who

Lawler (1971:158) documents "many companies' very

frequent claims that their pay systems are based on merit," despite, he continues, evidence from

several studies of a

low correlation between pay and performance.

Cleveland (1991) suggest that

evaluation.

90%

of private organizations use

&

recently.

Murphy and

some form of formal performance

Promotions are ideally supposed to allow firms to match individuals with jobs for which

they are well-suited, although this matching

Jensen

More

Murphy, 1988; Sorenson

The two firms

that

&

may

involve occasional or even systematic errors (Baker,

Kalleberg, 1981).

were selected

for this study (of twelve firms

approached) matched on a

in the periphery of the economy may make no pretense of

offering merit-based or other criteria; they simply offer work and pay, particularly to unskilled

workers who may have no other choices.

^Of course, sweatshops and establishments

15

number of important

charactenstics, including: both are in the

500 employees and

at least

(which makes

it

more

same industry (high technology), have

are at least 15 years old (so the job paths are stable), are not unionized

likely that merit rather than seniority

the formally

is

promotion (Freeman (1982)), conduct regular performance evaluations

for

espoused basis

for

in part to identify candidates

promotion from within, and have multiple levels of blue- and white-collar job grades.

As

I

learned more about the two firms,

of potential interest for this study.

Because of

ratings.

this practice,

I

found that they did not match on one characteristic

I

Company A

uses a forced normal distribution of performance

expect a steeper relationship

evaluation and belief that merit counts

Where

at

Company A between performance

a forced normal distribution

value high ratings more strongly (because they have more value where there

is

is

used, people might

no rating inflation and

high ratings are scarce), but not take seriously lower ratings (because they are artifactual of the

constraint

on managers

more reason

attribute

to

to attribute

them

fill

the bottom categories). Thus, those

them

to lack of merit.

equations (Firm

A

to merit, and those

dynamic

If this

who

is at

who

get the best ratings have

the

more reason

get the lowest ratings have

work, the interaction term that

all

I

will

add

to

to the

x performance evaluation received) should be positively related to beliefs about

merit.

Survey administration and response issues

The survey was

(called

distributed to

Company A and Company

mailed survey, but

still

low enough

845 employees

The response

B).

in

two firms

rate to the

that

have internal labor markets

survey was 51.8%, not unusual for a

that sources of response bias warranted examination.

a logistic regression to predict non-response, following the

method

in

1

performed

Berk (1983), and found

that

none of the available variables significantly differentiated between respondents and non-respondents.

1

was limited

to variables for

which

I

had information on non-respondents: detailed work group,

location code, and sex (the companies were not able to provide

employment

history,

and of course, data on

beliefs

is

me

with additional information about

always missing for non-respondents).

had information on the distribution of performance evaluations

for the entire population.

1

A

also

Chi-

16

squared

showed

test

purpose of

that

this study,

it

my

is

sample was not significantly different from the population.

particularly

good

that neither

For the

winners nor losers in the performance

evaluation contest are over- or under-represented.

Results

This section:

1)

presents the descriptive findings about beliefs and compares respondents'

beliefs about merit in the firm versus in the U.S.,

the preliminary concern that

2) addresses

respondents think merit ought to count, 3) creates the mobility rates normed for occupational group,

4) computes the relative return on education and tenure by regressing them on position, 5) presents

the results of the examination of Hypotheses

which proves to be an important variable

1

to 11, 6)

examines whether perceived advancement,

for understanding beliefs in merit,

is

correlated with actual

advancement, and 7) considers whether ambivalence about merit better characterizes some

respondents.

Pattern of

t)eliefs

about merit

Tables 2 and 3 show the means, standard deviations, and correlations for variables

study.

Responses to the questions about merit show there

variables, although the

mean

and luck (on the same

meritocratic.

variation in beliefs about the five merit

level of belief in the merit factors (about

not count" to "counts very much") compared to the

privilege

is

scale), suggests

mean

in this

5 on a 7-point scale from "does

level of belief in the "non-merit" items,

an overall tendency toward belief that the firm

is

Table 4 shows the frequency distribution of responses to the merit questions.

This study was motivated by national level studies of beliefs about inequality.

studies, the links

between

beliefs about national

This study has some preliminary data on

this issue.

In future

and organizational mobility can be tied together.

Individuals

meritocratic and that their workplace, about which they have

may

more

believe that the U.S.

sjjecific

information,

is

generally

is less so.

I

expected this pattern, particularly since questions about opportunity worded more specifically

17

generate lower levels of belief (eg

perceive there

is

.

Schlozman

&

Verba, 1978)

inequality in the U.S. ("out there"), but

my own

Alternatively,

situation in

which would be consistent with Lemer's (1980) theory of people's views of a

latter pattern is

It

firm

is

what

1

"just world."

is fair,

In fact, this

find for this sample.

meritocratic than that the United States

in the

be that people

my own company

appears, looking at the means in Table 5, that employees believe

and privilege

may

it

is

meritocratic

more strongly

Statements about

ability,

that the

hard work,

United States generate a lower mean and about the same variance as statements

about ability, hard work, and pnvilege in the more specific context of the workplace.

In addition, the beliefs about the national and the organizational opportunity structure appear

to be only moderately correlated.

Particularly since both questions

one might e.xpect a higher correlation simply as an

artifact

were asked in the same survey,

of the method.

It

appears instead that

employees' beliefs about merit in one context do not strongly relate to or inform their beliefs about

merit in the other context.

Whether respondents think merit ought

Before proceeding,

it

is

to count

necessary to check that the merit items

(hard

work,

ability,

performance) are what individuals generally think ought to count for advancement and that the nonmerit items (privilege, luck) ought not to count. This difference

results, for

example,

count in the

What

I

first

if

is

important for interpreting the

employees do not think hard work counts, but they do not think

place, then the interpretation should not suggest

some kind of

it

ought to

crisis of legitimacy.

have called "non-merit" items should be undesirable deviations from meritocracy, not

normatively desirable bases for deciding advancement.

item ought to count, on a 7-point scale.

distinction.

I

asked respondents to

rate

how much each

Their responses confirm the posited merit

/

non-merit

Merit items are rated high in the normative questions, and non-merit items are related

low. Table 6 shows the

means and standard

deviations.

18

Construction of the measure of upward mobility relative to job category

This variable

a

is

used as one of the three measures of mobility for Hypothesis

measure of each individual's mobility

7.

Because

this variable

relative to others in the

same job category,

specifications of mobility should be used

However, future work using

this data

if

not

is

it

the

made

a

human

used in testing Hypothesis

regressed position on education and tenure.

on education and tenure

A

shown

8.

in

Table

Table

The simpler

value.

might give more emphasis to organizational social groupings

Construction of the measure of relative return on

Harder (1992)).

in

more nuanced ones do not add explanatory

by Baron and Pfeffer (1989)

return

constructed

shown

focus of this study

that give rise to local social comparisons, as urged

is

as

I

proves to be only marginally significant in the equations in this study, and

other measures of mobility are stronger,

This variable

2.

3.

To

capital

calculate relative return

on human

capital

I

saved the residual to measure each individual's relative

I

(similar to the procedure used in Pfeffer

higher residual represents relative "over-attainment."

Separate regression equations for

and Lawler (1980) and

Results of this procedure are

Company A and Company B

are

shown (and

the

second of the two equations for each company just shows other exploratory measures of human

capital that

were not retained

for conceptual or empirical reasons).

Theoretically,

it

makes sense

to

run separate equations for the two companies, because individuals have within-firm information about

how

their position

compares with

relatively high or low.

for

Company A

is

that of others of similar education

Therefore, their return

much

higher than the

education and tenure explain

much more

is

R^

calculated relative to others in the

for

Company B

is

the log of

of the variance in position in

Because of the better

to

fit

not great in this study (studies where highly skewed income

income to improve

linear

fit

for

same

(.669 versus .175).

education and tenure on the log of position does not improve the

position

and tenure and whether

for

is

firm.

it

is

The R^

Differences in

Company

A.

Company

B; the skew in

Regressing

the dependent variable use

fit).

Company

A, relative return on education and tenure

have a stronger relationship to perceived advancement for employees in

Company

A.

may

That

prove

is,

in

19

Company

A, an employee whose return on education and tenure

too low relative to his or her

is

colleagues might be more aware of this under-altainment in a context where education and tenure

align

more closely with

contrast, in

in the

Company

company, so

position,

differently in the

it

may diminish

his or her perceived

advancement

In

B, other unmeasured variables appear to contribute to the variance in ptisition

relative return

To examine

advancement

and and

on education and tenure may be of

I

include an interaction term - Firm

the equations that estimate perceived advancement.

This term

importance for perceived

on education and tenure operates

the possibility that relative return

two companies,

less

A

x the attainment residual - in

not significant and

is

is

not

shown

in

the final results in Table 9.

Examination of Hypotheses

to 11

1

Results for Hypotheses

performance

1

to 7 are

shown

This study finds not only that perceived

in the firm's mobility contest is significant for

also that absolute position in the hierarchy

equation for

in Table 9.

how much

privilege counts,

suggests that the organization

is

is

generally not significant

which

significant relationships

Position in

tlie

is

(it is

only significant

in the

discussed further below). Again, this pattern

not vertically divided between believers in meritocracy nearer the top

and disbelievers nearer the bottom. Rather, there

In general, the equations

understanding beliefs about merit, but

are relative believers

do not explain much of

must be viewed against

is

in

every

level.

the variance (less than ten percent) in beliefs, so

this finding.

organizational hierarcliy. Hypothesis

positively to believing that advancement

and disbelievers

meritocratic.

to variance in beliefs about the three merit items

The

1

results

- hard work,

argues that position should relate

show

ability,

that position

does not

relate

and performance - nor about

the role of luck.

However, position does matter

is

for beliefs about

how much

privilege counts.

The

relationship

in the predicted negative direction. This finding says that people in higher positions believe less

strongly that privilege contributes to success, while people in lower positions believe

that privilege counts.

The

belief that privilege

does count

is

a potentially

more strongly

more radicalizing

belief

20

than the belief that hard work, abihty, or privilege does not count, so

found but not the

Because privilege

latter.

is

interesting that the former

counts, either people might be neutral about

it

it

because

it

is

is

ment

the counter-normative alternative to the idea that

is

language, or they have strong opinions about

it

unfamiliar and not part of corporate

(strongly positive or negative, depending

upon

their

position).

Performance evaluation.

Performance evaluation relates only to luck The better the

performance evaluation someone receives, the

do worse

in the contest to get the limited

the attribution that luck determines

less strongly they believe that luck counts.

Those who

good performance evaluations may find some comfort

who does

In interviews,

best.

in

some of those who received

excellent performance evaluations graciously acknowledged that there was certainly an element of

luck, particularly since performance (on the shop floor or at a desk)

anonymity of a survey, they appear

is difficult

to measure.

In the

to have been less likely to attribute importance to luck.

Perceived mobility. As predicted

in

Hypothesis

9,

perceived mobility has a significant

positive relationship to hard work, ability, and performance and a significant negative relationship to

luck and privilege.

five equations.

One

It is

the only variable that

shows

significant effects in the predicted direction in all

of the main findings of this study

is

that perceived mobility is significant for

understanding beliefs about merit.

Performance evaluation discrepancy. Higher discrepancies (deserved minus

actual

performance evaluation) indicate greater disappointment with the performance evaluation received.

This variable

is

significant in the predicted direction in

two equations (hard work and luck) and

marginally significant in two equations (performance and privilege).

Employees who

are

more

disappointed feel less strongly that hard work and performance count, and feel more strongly that

privilege

and luck count.

Upward

mobility, relative return on tenure

boundary, being a manager.

and education,

lateral

Contrary to the predictions in Hypotheses

these variables have a significant relationship to beliefs about merit.

moves, crossing a class

2, 3, 5, 6,

and

7,

none of

All these variables have the

advantage, discussed above, of being "quasi-objective" measures of individuals'

employment

21

experience and history.

While

this is a mcthcxlological

advantage,

it

may

also

mean

inasmuch

that,

as

these variables are constructed by the researcher and not reported by employees, these variables

do

An employee may

not

not reflect

some understanding

the respondent has of his or her experience.

need to "make sense of" these experiences by believing to a greater or lesser extent

merit

if

these experiences are not salient in the

An

alternative interpretation

perhaps with some noise.

may

is

first place.

that these experiences

This possibility

is

in the role ol

do contribute

advancement,

to perceived

The perceived advancement

explored below.

already capture the role of these variables.

Tenure.

Tenure has a significant negative relationship both to the belief

employees may

work

that hard

counts and to the belief that ability counts, in the direction predicted in Hypothesis

just

variable

Newer

8.

with a belief that hard work and ability are rewarded, perhaps because they have

start

come from school

or start with

new

priors that their

new company

is

a meritocratic place.

longer tenure, employees believe less strongly that hard work and ability count.

Their beliefs

decrease with tenure, perhaps because as options close and careers settle to a certain pace, they

feel that their

own

hard work and ability

is

not,

is

Sex. Sex

not simply true for people

is

This result

performance

who

when mobility

is

controlled

for.

The

are frustrated about not being mobile.

not related to beliefs about merit, contrary to Hypothesis 11.

Occupation.

counts.

may

on the margin, delivering better advancement. Tenure

per se must be driving negative relationship, which remains even

effect of tenure

With

is

Employees who

are in Production are less likely to believe that

surprising, since the stereotypical view of Production

measures

on

which

to

base

evaluations

and

is

that

performance

has more usable

it

advancement

do

than

the

business/administrative or engineering occupations, which are thought to include more projects that

are

ambiguous, long-term, or accessible only by similarly skilled members of what Williamson and

Ouchi (1981)

call a "clan."

In fact, what

precisely because performance

arbiter of

who

is

may

be going on

is

that Production

employees can

measurable and not socially constructed, that performance

is

see,

not the

gets ahead.

Firm. Only one main

effect of firm is found.

Employees

in

Company A

are less likely to

22

believe that hard

work

counts.

The

may

structure of the performance evaluation system

contribute to

this belief.

Interaction of

is

steeper for

Firm A and performance evaluation. The

Company A

(the interaction term for

Perhaps

many employees

evaluations limits the

number who can

evaluations to some.

Those

significant).

strongly that hard

in

determining

who

gets

A

and performance evaluation

is

and

positive

they work hard, but the forced normal distribution of

feel

get the highest evaluation and forces managers to give low

Company A who do

work counts than those who

get stuck with the poor ratings in

Firm

slope for performance evaluation

Company A

Company

get the top evaluations in

B.

are even less likely to believe that hard

(Dummy

which evaluations.

performance evaluation can be included

well in this competition believe even

in future

work

variables

for

to estimate

And

those

more

who

work counts

for

four of the five levels of

more precisely the return

to

performance evaluation.)

Overall, perceived advancement

explained in these five equations.

advancement

relates to actual

important for the small amount of variance in beliefs

is

The next

section considers the extent to

advancement, particularly in

which perceived

light of the surprising finding that

none of

the "quasi-objective" measures of employees' experiences in the advancement contests in the firm

is

significant.

The

relationship of actual advancement experiences to perceived advancement

This study proposes that individuals might cope with meritocracy by embracing the belief in

Another way in which they might cope

merit to differing degrees.

While

true success in

advancement contests

is

limited, individuals

is

to believe they are successful.

may

perceive themselves to be

successful, whether because of inflated impressions or because other kinds of success are possible in a

variety of local contests.

person

who

may

assist the individual.

For example, a

has not experienced any upward mobility in an organization might nonetheless feel

successful if he or she has

done.

Local constructions of success

made

Indeed, the current

frequent lateral

move toward

moves

flatter

that

add interesting change to the work to be

organizations and more job rotation requires

23

corporations to encourage employees to regard such moves as

real,

not illusory or consolatory,

representations of success, while a critical sociological approach might regard these "satisfying" lateral

moves

as

mere

(eg, Baron

illusions of mobility

&

Bielby, 1986); these normative views are not

adjudicated herein.

It

worse to the extent

better or

answer

(e.g..

seems very straightforward

is

not as trivial as

Kinder

&

it

that their

may

to predict that individuals perceive their

advancement has actually been

at first appear.

Sears, 1985), as

is

The

the relationship

links

advancement

to be

relatively better or worse. This

between experiences and beliefs

is

complex

between behaviors and attitudes (eg., Ajzen

&

Fishbein, 1977). Psychologists have identified factors that might attenuate the relationship between

experiences and perceptions. Motivations

and nurture "positive

may

might naturally want to deny

intervene: people

illusions" (Taylor, 1988) about their success.

These mechanisms notwithstanding,

I

expect that, at the workplace, people's perceptions of

their mobility will be fairly well in line with their actual mobility

may

be hard to sustain.

The evidence of how well one

is

doing

At the workplace, positive illusions

is

constantly present, whether in the

form of a weekly paycheck, of promotion announcements of peers, or of having

a superior vested with the greater authority of a higher position.

to take orders

one to adduce to predict simply

the appropriate

is

that actual relative mobility experience relates to perceived relative

mobility experience, this view of the particularities of the workplace suggests a significant

Perceived advancement

relative return

is

on human

capital,

performance evaluation,

The

results are

moves, crossing a

shown

in Table

Advancement experiences other than upward mobility, experiences

be considered ancillary to upward mobility, are included alone

the second equation, the addition of

for

lateral

and

1 1

Overall, actual experiences explain about twenty percent of the variance in

perceived advancement.

method

link.

regressed on the variables from the preceding analysis - position,

boundary, being a manager, tenure, sex, occupation, and firm.

discussed below.

from

These reminders may make denial

or positive illusions a tenuous coping strategy. While no particular body of theory

upward mobility,

failure

upward mobility

comparing nested models

in

in the first

rate significantly

that

may

of the three equations.

improves

R^

In

(following the

Wonnacott and Wonnacott (1977:434-436).

The other

24

factors alone

do not explain perceived advancement

as well as the equation including the

most

direct

measure of actual advancement, although they can explain about sixteen percent of the variance

in

In the third equation, demographics and controls are included, but none

perceived advancement.

contribute significantly.

Position in

tlie

organizational hierarchy. The findings show that position does not relate to

As above,

perceived advancement.

the lack of a significant role for position suggests that perceptions

of success are not vertically stratified and clustered

at the top.

It

is

possible that the nature of the

dependent variable prompts respondents to think in terms of how they have advanced, rather than

where they have

arrived.

A

broader question about satisfaction with one's status in the firm might

have produced a significant relationship with position. In terms of the mobility contest specifically, a

higher position does not apjsear to relate to a greater sense of success in the mobility contest.

Performance evaluation. Performance evaluation

has a significant positive relationship to

Those who

get higher evaluations perceive that their

perceived advancement, in

all

three equations.

Many

advancement overall has been good.

performance evaluations, and in

my

interviews,

I

studies

found

find

that

that

employees

process

(e.g.,

Ilgen

&

to this

&

Feldman, 1983; Murphy

and perceived procedural fairness of what

is

cynical

about

employees who had gotten high and low

ratings insisted they did not take performance evaluations very seriously.

improving performance evaluations responds

are

Much

of the literature on

cynicism and focuses on how to improve the

Cleveland, 1991) in order to increase the credibility

taken to be an unfortunate aspect of the organizational

governance structure. The strong positive relationship between performance evaluation and perceived

advancement

in this study suggests that people

entirely cynical about the signal

so entirely mollified by

fair

it

who

sends and people

receive high performance evaluations

who

may

not be

receive low performance evaluations are not

procedures that they perceive themselves to be doing just as well.

Relative return on education and tenure.

Relative return on education and tenure (also

labeled "attainment residual") had only a marginally significant positive relationship to perceived

advancement and was not significant with

all

the controls added.

As discussed above,

the advantage of being a quasi-objective measure constructed by the researcher.

At

this variable has

the

same

time.

25

because

survey,

it

constructed by the researcher rather than obtained as an attitudinal measure from the

is

it

has the disadvantage that

measure from which

it

may

be,

however, that employees

college or

who

in

are

commonly used

in social science

who

if

survey research.

these courses were pitched as

ways

may compare

to

their attainment to

improve one's

research can pursue multiple and more detailed measures of this variable, which

significantly related both to perceived

Upward

movement

variables,

advancement and

to beliefs

Future

career.

may prove

to be

about merit.

Actual upward mobility rate had a significant positive relationship to

mobility.

perceived advancement.

It

get a degree in a particular subject at a nearby

take a particular on-site course to upgrade their skills

one another, particularly

for the

an organization make more detailed comparisons about more

For example, people

specific types of training.

The education

was derived asked only about terminal degrees (except

this variable

"some college" category); these categories

may

not tap the social reality of the res[X)ndent

(The equations were also run including,

which was significant

others in one's job category,"

which

is

in the equations,

in separate turns, the

absolute

and the variable "mobility relative

only marginally significant.) This seemingly simple result

to

is

a

contribution of this study, because this relationship has been assumed or overlooked, but not

empirically demonstrated.

While appealingly simple,

Lateral moves (recent).

That

advancement.

lateral

moves can

for example,

was not a foregone conclusion.

this result

This variable has a significant, positive relationship to perceived

this variable is significant in addition to actual

upward mobility suggests

that

contribute independently of actual mobility to the perception of advancement.

two employees both have zero

overall mobility rates, but

one has made two

lateral

If,

moves

recently, that person should perceive slightly better advancement, despite the fact that the stark zero

mobility rate

is true for

both.

(49.7%) report no recent

4 moves.

That

This lateral

is,

move

In this sample, of the 177

lateral

employees who have zero mobility

moves,, while 66 (37.3%) report

half the people with zero

upward movement

1

rates,

88

move, and 23 (13.0%) report 2

to

report at least

contributes positively to their perceived advancement and

them the lower perceived advancement they would have on the

Crossing a class boundary.

1

may

recent lateral move.

partly ameliorate for

basis of their zero mobility rate alone.

The experience of crossing a

class

boundary contributes

26

positively to the perception of advancement

This result

is

consistent with interviewees' reports that

number of

positive experience, even controlling for actual

this is a particularly salient

levels

advanced.

Tenure.

included.

First,

Two

Tenure

is

not significantly related to perceived mobility once

may

increase an employee's sense of general satisfaction, including feelings about

advancement. Chinoy (1956) found

workers and attributed

it

this positive relationship

of tenure to satisfaction for automobile