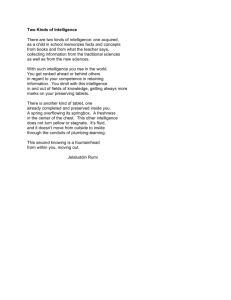

Chapter 18 Intelligence

advertisement