Document 11045257

advertisement

LIBRARY

OF THE

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of Health Teams

by

Irwin M. Rubin and Richard Beckhard

M.I.T. Working Paper

//

561-71

October, 1971

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

50 MEMORIAL DRIVE

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 021

MASS. INST. TEChI

I

1

I

Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of Health Teams

by

Irwin M. Rubin and Richard Beckhard

M.I.T. Working Paper

//

561-71

October, 1971

The action-research intervention discussed in this paper

was carried out at the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Health

Center in the Bronx, New York. The effort was supported

through grants from Montifiore Hospital and the Carnegie

Corporation.

This paper will be published in the Milbank Quarterly and

should not be quoted in any part without permission from

the authors.

OCT 21 1971,

DEWEY LIBRARY J

nd 5^1-71

Dewey

SEP 101975'

RECEIVED

OCT 21

M.

I.

T.

1971

UbKArtitS

Group practice in health care delivery takes many forms.

The term

"group practice" usually refers to a group of colleague professionals who

combine their resources in delivering treatment care to a patient population.

Some of these groups are actively involved in preventive medicine efforts.

Because of hea-vy work loads, more and more activities are being delegated

to nurses, physicians assistants,

health workers.

and, in some cases, community based family

One common condition in all of these settings is that a

group is doing the

"

practicing ."

The effectiveness of any group in any setting is related both to its

capabilities to do the work and its ability to manage itself as an interde-

pendent group of people.

The central focus of this paper will be upon the

internal dynamics involved when a collection of individuals attempt to function

as a group.

Our objective is to provide a framework which will facilitate

consideration of several important issues involved in the more effective

utilization of groups in delivering health care.

We will begin by drawing upon the general body of knowledge about groups

and their dynamics developed within the behavioral sciences.

Several key

variables known to be of prime importance in any group situation will be

discussed.

Next, we will discuss the particular relevance of these variables

to group medical practice.

Third, we will draw upon our own experience in helping several health

teams improve their effectiveness.

The setting for this effort was a

community health center, located in a low income urban area, concerned with

providing comprehensive family centered health care using health

633180

C5I

-2-

teams

1

as the

main

II

delivery system."

--^

„_J:

"''

2

We will then discuss some issues which we feel apply to a variety of

health care delivery settings, where groups are collaborating on the

delivery.

Finally, we will indicate some issues for the education and training

of health workers who will be functioning in groups.

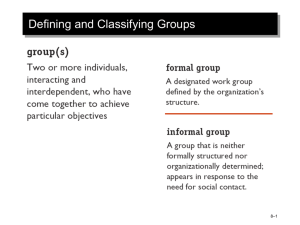

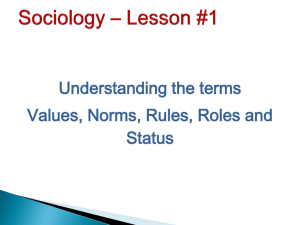

THE DYNAMICS OF GROUPS

In this section, we will present and briefly define, seven selected char-

acteristics or variables known to be of importance in any group situation.

Each characteristic can be viewed as a scale or yardstick against which one

can ask the question: is this particular group (made up of certain kinds of

people, trying to do a given task in this situation) located where it needs

to be on each of these scales to function most effectively?

Goals or Mission

A team or group has a purpose

.

There exists a reason (or reasons) for

the formation of the group in the first place.

In any group, therefore, there

will be issues like:

1. The "average" team in this center consisted of a full-time internist,

a full-time pediatrician, 2 full-time nurses, and 4-6 full-time family health

workers drawn from the community. Available on a part-time basis were a

dentist, a psychiatrist, in addition to the back-up support of x-rays, labs,

and the like. A team was responsible for 1500 families in a particular geographical area.

2. We pay little attention in this paper to the very important question

of the organization of which the health team is a part.

For an intensive discussion of the organizational issues involved in the delivery of health care

see Beckhard, R.

"The Organizational Issues in Team Delivery of Health Care,"

in this same volume.

,

3. For an excellent and readable description of group process, see

Schein, E. H. , Process Consultation , Reading, Mass., Addi son-Wesley, 1969.

For a more general introduction to the field of organizational psychology see

Schein, E. H. , Organizational Psychology , Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey,

Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1965.

-3-

who sets the goals?

(a)

how clearly defined are the goals?

(b)

how much agreement is there among members concerning the goals?

how much commitment?

(c)

how clearly measurable is goal achievement?

(d)

how do group goals relate to broader organizational goals?

personal goals?

to

Since a group's very existence is to achieve some goal or mission, these issues

are of central importance.

Role Expectations - Internal

In working to achieve their goals, group members will play a variety of

roles

.

There exists among the members of a group a set of multiple expectations

concerning role behavior.

Each person, in effect, has a set of expectations

of how each of the other members

its goals.

a)

4

should behave as the group works to achieve

In any group, therefore, there exists questions about:

the extent to which such expectations are clearly defined and communi-

cated (role ambiguity)

b)

the extent to which such expectations are compatible or in conflict

(role conflict)

c)

and, the extent to which any individual is capable of meeting these

multiple expectations (role overload).

These role expectations are messages "sent" between the members of a

group.

Generally, the more uncertain and complex the task, the more salient

are issues of rol?6 expectations.

4. For an excellent study of this concept of role sets see, Kahn, R. N.

et al Organizational Stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity

New

York, Wiley, 1964.

,

.

Role Expectations - External

Any individual is a member of several groups.

Each group of which he is

a member has expectations which can influence his behavior.

The Director of

Pediatrics in a hospital, for example, is "simultaneously" the manager of

of the funchis group, a subordinate, a member in a group of peers (Directors

tional areas), a member of a hospital staff, a father, husband, etc.

Each of these "reference" groups, as they are called, holds expectations

of a person's behavior.

overload.

Together they can be ambiguous, in conflict, or create

--

These multiple reference group loyalties can create significant prob-

lems for an individiial in terms of his behavior as a member of a particular

group.

While the source of the conflicts involved in the question of reference

group loyalties is external to a particular group, they can have significant

internal effects.

Decision-making

A group is a problem-solving, decision-making mechanism.

This is not tc

imply that an entire group must always make all decisions as a group.

The

issue is one of relevance and appropriateness; who has the relevant information

and who will have to implement the decision

.

A group can choose from a

range of decision-making mechanisms including decision by default (lack of

group response), unilateral decision (authority rule), majority vote, consensus,

or unanimity.

Each form is appropriate under certain conditions.

Each will have different

consequences both in terms of the amount of information available for use in

making the decision, and the subsequent commitment of members to implement the

decision.

Similarly, when a group faces a conflict it can choose to (a) ignore it,

(b)

smooth over it, (c) allow one person to force a decision, (d) create a

-5-

compromise, or (e) confront all the realities of the conflict (facts and

feelings) and attempt to develop an innovative solution.

The choices it

makes in both of these areas will significantly influence group functioning.

Communication Patterns

If, indeed, a group is a problem-solving, decision-making mechanism, then

the effective flow of information is central to its functioning.

Anything which

acts to inhibit the flow of information will detract from the group effectiveness.

At a very

There are a range of factors which affect information flow.

Meeting space

simple level there are architectural and geographical issues.

can be designed to facilitate or hinder the flow of communication.

Geo-

graphically separated facilities may be a barrier to rapid information exchange.

There are also numerous more subtle factors.

Participation - frequency,

order, and content - may follow formal lines of authority or status.

High

status members may speak first, most, and most convincingly on all issues.

The

best sources of information needed to solve a problem will, however, vary with

the problem.

Patterns of communication based exclusively on formal lines of

status will not meet many of the group's information needs.

People's feelings of

freedom to participate, to challenge, to express opinions also significantly

affect information flow.

Leadership

Very much related to the processes of decision-making and communication

is the area of leadership.

To function effectively, a group needs many acts

of leadership - not necessarily one "leader" but many leaders.

People often

misinterpret such a statement as saying "good groups are leaderless."

is not the intent.

This

Depending on the situation and the problem to be solved,

different people can and should assume leadership.

The formal leader of a

group may be in the best position to reflect the "organization's" position on

a particular problem.

Someone else may be a resource in helping the formal

leader and another member clarify a point of disagreement.

of necessary acts of leadership

.

All are examples

It is highly unlikely that in any group

there will be one person capable of meeting all of a group's leadership needs.

Norms are unwritten (often untested explicitly) rules governing the be-

havior of people in groups.

They define what behavior is "good or bad,"

"acceptable or iinaccep table" if one is to be a functioning member of this group.

As such, they become very powerful determinants of group behavior and take on

the quality of laws - "it's the way we do things around here!"

when they are violated

is most clear

—

seat, joking reminders, are observable.

to expulsion

—

quiet

Their existence

uneasiness, shifting in one's

Repeated violation of norms often leads

psychological or physical.

Norms take on particular potency because they influence all of the other

areas previously discussed.

Groups develop norms governing leadership, influence,

communication patterns, decision-making, conflict resolution and the like.

herently, norms are not good or bad.

a

The issue is one of appropriateness

In-

—

particular norm help or hinder a group's ability to work.

These seven factors, then, are characteristics of any group situation.

a

does

particular group needs to be on each of these "yardsticks" is a function of

the situation.

health teams.

We turn now to look at these factors within the setting of

Where

The Dynamics of a Health Team

Our intention in this section is to look at these factors affecting

group functioning and to relate them to a group

total health care).

setting (community based,

The Center in which we have worked

is

situation from which we will draw examples and observations.

the particular

However, the

issues raised are, in our view, very broadly relevant.

Goals or Mission

A health team striving to provide "comprehensive family centered health

care" faces uncertainties substantially different from those one might find in

a hospital setting.

The goals

in a hospital are relatively clear: remove the

Success is measurable and clear.

gall stone, deliver the baby.

social factors of prime importance.

Seldom are

The thrust is curative and the emphasis

is medical.

The community oriented health teams we have studied experience considerable

uncertaintly over their mission.

"Comprehensive" means the team can not ignore

social problems and emphasize the "relative security and certainty" of medical

5. By group practice we mean situations wherein people are together over

long periods of time working on a common task. More temporary groups like the

group formed to do a particular operation in a hospital are not included in our

discussion. Even in many temporary groups, such as short duration task forces

or committees, many of the process factors discussed can be observed to be in

operation.

6. For a more detailed preliminary report of our activities in this setting

see: Fry, R.E. and Lech, B.A,

An Organizational Development Approach to Improving the Effectiveness of Neighborhood Health Care Teams: A Pilot Program

Unpublished Masters thesis, Sloan School of Management, M.I.T., June 1971.

(copies available from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Health Center, 3674 Third

Avenue, Bronx, New -York 10456).

,

7. If one takes a total hospital as a group, many similar issues appear.

Revens, for example, argues that the central task in a hospital is the

management of anxiety. This is very analogous to the position we take vis a vis

a health team.

The only difference is that the problems are more visible in

the smaller social system of an on-going group.

See Revens, R.W., Standards

for morale: cause and effect in hospitals , London: Oxford University Press, 1964.

There is considerable anxiety generated because the team does not

problems.

really know when and if it is succeeding.

The questions of priorities and time

allocations become complicated; how does one decide between competing activities

in the absence of clearly defined goals?

A team member wonders if she should

spend one-half a day trying to arrange for a school transfer for a child or

should she see the other patients scheduled for visits.

No one member of the team has been trained to be knowledgeable in all

the areas required.

Yet, the complexity of the task demands that doctors be-

come involved in social problems; nurses become the supervisors of parapro-

fessional family health workers who are an integral part of the team; and these

community based family health workers become knowledgeable in diagnosing and

treating psychiatric problems.

This is not to say everyone should become an

'"---

expert at solving all problems. The requirements are for considerable information

collection, sharing, and group planning so that the team has all the available

information to deploy its total resources to the task.

The anxieties and frustrations created by the complexity of the task are

inevitable - an inherent part of providing "comprehensive" care.

g

A major

team dilemma is one of managing short vs. long run considerations - to give

itself short run security and direction while not losing sight of its long run

vague and global goal.

Role Expectations - Internal and External

The nature of the task

—

comprehensive family centered health care

demands a highly diverse set of skills, knowledge, backgrounds.

—

In creating

a team, many "cultures" are of necessity being mixed and asked to work together.

A very useful tool for diagnosing the forces impinging upon a team

For more detail, see Fry and

8.

is called life space or force field analysis.

Lech, op. cit. , and an article by Kurt Lewin,

and

in Bennis, W., Benne, K.

Chin, R.

The Planning of Change , New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 2nd

edition, 1969.

,

,

,

-9-

As a result of educational background and training, the doctors are ac-

customed to being primary (if not sole) authority and most expert in medical

issues.

The specialist role for which they have been so well trained and which

is so appropriate in a hospital setting comes under pressure.

in addition to his specialist skills,

As a team member,

the doctor is asked to become more of a

He needs to teach other health workers some of his medical know-

generalist.

He also needs to learn from them more about the social problems facing

ledge.

the community and the character, mores, and values of the particular patient

population.

Doctors tend to maintain strong

speciality groups.

it will be for

psychological ties with their professional

The stronger these ties for a physician the more difficult

His sense of professionalism

him to develop needed team loyalty.

stems from these external reference groups.

The careful hospital-type workup

he has been so well trained to do may not be feasible or appropriate in the

face of the hectic schedule generated by large nmnbers of patients.

flict nay become one around "professional standards."

The con-

Comprehensive group practice

may require a redefinition of these standards and perhaps even the redefinition

of a professional.

Both the nurses and family health workers tend to bring a history of sub-

missiveness.

The nurses have been trained to be submissive to doctors.

In this

setting, nurses find themselves as coordinators of the work of a team including

doctors

—

a complete role reversal.

Family health workers in this case are -local

community residents,

who, after six months of clinical training, suddenly find themselves

defined as "colleagues" with middle class physicians.

a

They bring

deep concern for social problems coupled with the best understanding of

what will/will not work with patients (their friends and relatives!).

The

\

/

-10-

teain

needs their knowledge of the cultural norms of the community and their

commitment to social issues.

Their background and passive posture is often

a barrier to the realization of these expectations.

Whereas the nurses and doctors have a professional reference group, the

family health workers as yet have none.

The resulting feelings of "homeless-

ness" are heightened by their liason role at the interface between the team

and the community.

9

Their membership and acceptance in the community is

crucial to the team's ability to be of service.

They alone can serve to bridge

the cultural gaps which exist.

This set of conditions differs markedly from the hospital setting where

strong reference group loyalties and clearly defined role expectations are

common.

Behaviors learned during one's individual preparation are appropriately

applicable in the vast majority of situations.

Although professionals and

paraprofessionals work in the same organization, seldom, if ever, are they

asked to work in highly interdependent on-going stable groups.

A part of being a member of a highly interdependent team is the need to

develop new loyalties and learn how to do some new things - not anticipated

or covered during individual training.

In fact, it is very unlikely that,

in the face of the mission of providing "comprehensive family- centered health

care," clearly defined complete job descriptions will ever be feasible.

9. Such people have been called marginal men.

A foreman in a factory is

another example - caught between the management culture and the worker culture.

10. The very notion of a team approach to the delivery of health care may,

for example, force a redefinition of the norm of privacy between doctor and

patient.

The norm may need to be adapted to encompass team and patient.

11. Many organizations are realizing the needs for such fluid role relationships. A job is now viewed as "a man in action in a particular situation

at a particular moment."

Such "job descriptions" must be constantly renegotiated and updated to account for both changes in the man and the situation.

-11This reality puts great stress on a team's ability to learn and adapt by

itself.

In response to a particular problem,

the question can not be "Whose

job is it?" but may instead have to be "Who on the team is capable? or "Who

needs to learn how to handle this situation?"

Decision-making

The inherent uncertainties in its mission and the diverse mix of skills

represented on a health team suggest that decisions can seldom be appropriately

made in a routine, prograinmable, or unilateral manner.

This is in sharp con-

trast to the majority of cases in the hospital setting where there is the relative clarity and certainty of the goals and clearly defined roles and lines of

authority.

One difficulty in any on-going team is the need to differentiate a variety

of decision-making situations.

In an attempt to be "democratic and participa-

tive" a team might try to make all decisions by consensus as a team.

sents a failure to distinguish, for example,

(a)

This repre-

who has the information neces-

sary to make a decision, (b) who needs to be consulted before certain decisions

get made, and (c) who needs to be informed of a decision, after it has been

made.

Under certain circumstances, the team may need to strive for unanimity

or consensus - in other cases majority vote may be appropriate.

Perhaps the greatest barrier to effective deci si on -making in highly

interdependent health teams stems again from the "cultural" backgrounds of

team members.

Doctors are used to making decisions by themselves or in col-

laboration with peers of equal status

professionals.

—

other doctors or highly educated

At the other extreme, the community residents who work on the

team are used to being passive dependent recipients of others' decisions.

Yet many times, on a health team, the doctor and the community workers are

and must behave as peers - neither one possessing ail the information needed

-12-

to solve a particular problem or make a particular decision.

Furthermore,

there are many times when the doctor is the one who needs information held

by another health worker.

When a conflict develops, the required discussion

which will lead to consensus is difficult to achieve; forcing, compromise,

or decision by default may result.

Commitment to decisions is low with the

result being that many decisions have to be remade several times

we decided that last week!"

—

"I thought

or "Didn't we decide that you would do such and

such?"

The team approach to delivery of health care puts great stress on the need

for numerous and various inputs to many decisions.

When the decision-making

process is inappropriate, less information is shared, commitment is lowered,

'

and anxiety and frustration are increased.

Communication Patterns/Leadership

Issues of communication patterns and leadership can be handled together

for, as was true in the case of decision-making as well, the central theme is

one of "influence."

The leadership or influence structure

—

to which we

have all become so accustomed via our family, educational, and organizational

experiences and which is appropriate for say a hospital operating room, will

be incapable of responding to the diversity of issues with which a health

team must deal.

In this setting each member is a resource.

open channels to all the other members.

He must have

Because of the complexities in this

type of group, a number of communication norms are required: openness (leveling)

and a person-to-person relationship which has enough mutual trust to enable

each person to "tell it like it is."

Team practice can not work if roles talk to roles - a much more personal

mutual dependency is required.

Influence, communication frequency, and leader-

ship should be determined by the nature of the problem to be solved not by

]

.

-13-

hierarchical position, by seating position, educational background, or social

status.

With respect to leadership, in particular, the teams we have studied relied on the model they knew best

—

in this case

"

follow the doctor ."

Con-

tinued reliance on that model will result in an overemphasis on medical vs.

social issues, a lack of shared commitment to decisions (which doctors sometimes interpret as "lack of professional attitude")

,

and less than complete

sharing of information, all of which affect the task performance directly.

Norms

Much of what we have described is reflected in a group's norms

.

The

teams we have studied have exhibited several powerful norms:

(a)

"in making a decision silence means consent;"

(b)

"doctors are more important than other team members," - "we don't

disagree with them;" "we wait for them to lead;"

(c)

conflict is dangerous, both task conflicts and interpersonal disagree-

ments - "it's best to leave sleeping dogs lie;"

—

(d)

positive feelings, praise, support are not to be shared

(e)

the precision and exactness demanded by our task negate the opportunity

"we're all

'professionals' here to do a job."

to be flexible with respect to our own internal group processes

[this

may be a carry-over from the hospital operating room environment where

the last thing you need is an innovative idea as to how to do things

better!

The effects of these norms, and others like them, is to guarantee that a team

gets caught in a negative spiral.

12

While the norms are those of rigidity, the

12. It is in this regard that our thinking is very similar to Revens

The ineffective management of inherent anxiety results in more anxiety creating

a negative feedback loop and a self-reinforcing downward spiral.

See Fry and

'

Lech, op. cit.

-14-

complexity of the environment and the task to be done demand flexibility.

The frustrating, anxiety provoking quality of the task places great demands for

some place to recharge one's emotional battery.

The team is potentially such

a place.

In addition to these specific norms of flexibility, support, and openness

of communication, there are a set of higher order norms which are essential.

Task uncertainty and environmental changes require that a team develop a

capacity to become self-renewing

—

become a learning organism.

Learning

requires a climate which legitimizes controlled experimentation, risk taking,

failure, and evaluation of outcomes.

In the absence of norms which support

and reinforce these kinds of behaviors, a team will end up fighting two

enemies - its task and itself

.

There exists, in other words, a unique connection between what a team

does

[its task]

and how it goes about doing it [its internal group processes ].

At a very simple level, the health care analogy would be: if a team is to treat

a family as

an integrated vmit [its task], the team itself must, in many ways

operate as a highly integrated "family unit" [its internal group processes].

Without this ability to maintain itself a health team will, like many other

"pieces of equipment" eventually

bum

itself out.

In the interim, work con-

tinues to get done but more and more energy is demanded to "move the machine

forward."

To siimmarize, the internal process issues we have discussed will occur in

any group.

They can not be wished away or ignored for long without some cost.

Nor are they the result - as is frequently assumed - of basic personality

problems.

More often team members have difficulty functioning together because

of ambiguous goal orientations, unclear role expectations, dysfunctional

deci si on -making procedures and other such process issues.

•15-

If a health team is first to survive and second to grow,

it must,

as

we have said, develop an attitude and a capability for building and renewing

itself as a team.

It can do this first by becoming aware of how its internal

group processes influence

its ability to function and second by learning how

to manage these process or maintenance needs in a more productive manner.

We turn now to a brief case illustration of an effort aimed at helping health

teams move closer to this ideal of becoming self-renewing or learning organisms.

A CASE STUDY OF A HEALTH TEAM IMPROVEMENT EFFORT

13

Our efforts at helping teams improve their functioning relied heavily upon

a very simple but powerful model - the action research approach.

14

The basic

flow of activities can be depicted in the following manner:

Summarization

Data

Collection

and

Feedback

Action

Planning

Evaluation

In this setting, the initial activity with a health team involved inter-

viewing each member individually - using both open-ended questions and check

list ratings.

Questions asked related directly to the seven process factors

discussed earlier such as team goals, levels of participation, decision-making

styles, etc.

These data were then stmimarized and fed back anonymously to the

entire team.

13. Our initial efforts at intervening into two health teams are reported

We have to date completed initial interin detail in Fry and Lech, op. cit.

Similar activities are planned for other teams

ventions with six health teams.

in the future as well as follow-up activities to reinforce our initial efforts.

Four of our students, Ron Fry, Bern Lech, Marc Gerstein, and Mark Plovnick

have worked closely with us in these efforts.

—

14. For an excellent description of this model and its applicability in

a wide variety of situations see Beckhard, R. , Organization Development:

Strategies and Models

,

Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley

,

1969.

-16-

Team members' reactions to the data presented during this feedback, session

were varied.

For some, the result was one of surprise

people felt that way about this team!"

their own concerns widely shared.

—

"I didn't realize

Others were surprised to find many of

Before the feedback session, many people

believed they were the only ones experiencing certain difficulties.

The most

frequent reaction could be characterized as follows: "These problems have been

—

around

under the surface

—

for a long time.

Now they have been collected,

summarized, and are out on the table for all of us to see."

The teams, in other words, were provided with an im^ge or picture of their

present state based on information (feelings as well as facts) collected from

the most valid sources available

of the interview feedback process

—

,

the team members themselves.

teams owned the information

were used to exemplify a particular issue

state

—

)

As a result

(Verbatim quotes

and shared the image of their present

"it's out on the table for all of us to see."

These two elements of

shared ownership helped to create a heightened desire and commitment on the part

of team members to solve their problems.

In order to cope with the large number of complex problems reflected in

the information and to move most effectively into action planning, the health

teams had to:

a)

prioritize the multiple issues reflected in their data;

b)

decide upon the most appropriate format to use (total group, homogeneous

vs. heterogeneous subgroups, etc.)

c)

to generate solution alternatives;

develop a clear and shared set of change objectives or goals

—

an

image of what a more ideal or improved state would be;

d)

allocate individual and subgroup responsibilities to implement chosen

actions;

e)

and, specify mechanisms and procedures for checking progress (follow-up).

-17-

The problem-solving skills, attitudes, norms, etc. needed to accomplish

the above "process work" were very similar to behaviors needed to successfully

accomplish "task work."

This unique connection between task and process can

be clarified with the following example.

A salient problem in each health team concerned their regularly scheduled

1

1/2 hour weekly team conference meetings.

These meetings represented the

one time each week when the entire team met together.

The intent was to discuss

patient family cases, learn from each other's experiences, work on common probllems and the like.

The pervasive feeling with regard to these meetings was one

of frustration and dissatisfaction.

time

They were dull, a waste of time, and a

for some people to "lecture" about their pet topics.

The way the team managed itself (its process) during these meetings

in fact made the situation more difficult.

The negative spiral to which we

referred earlier was operating to drain energy and commitment required to

solve patient problems.

The specific action plans developed and subsequent team improvement inter-

ventions were, in each case, a product of the particular issues reflected in

the data collected initially from a team.

Regardless of the problem, the same

action research model, with minor variations was applied.

For example, action

plans aimed at improving the team conference meeting included:

(a)

the formation of agenda planning committees;

(b)

systems of rotating chairmen to help all team members enhance their

skills at running a meeting;

(c)

designation of observers, on a rotating basis, to help the team evalu-

ate - at the end of each meeting - the impact of its own group dynamics.

15. In several cases, these observers were part of the next agenda planning

committee.

The data collected by the observers, in other words, was quickly

used as an input into the next action planning phase.

;

.

,

-18-

While many consultant interventions were aimed at helping a team to solve

problems it presently felt, longer run considerations also guided consultant

behavior.

Whenever feasible, a team was helped to see the connection between

what they were doing (their task) and how they were going about it (their

internal group process).

This expanded awareness helped to develop an attitude

(norm) toward change which legitimized managed experimentation and learning

.

In other words, if a team is to become self-renewing, it must be willing to

experiment ia a controlled way - to try new ways of working, evaluate and learn

from the consequences of these efforts

,

and use this new learning in the plan-

ning and implementation of future efforts.

On the assumption that the action

research approach we used represented a generalizable problem-solving model

we continuously worked to help the teams to internalize this model so that they

could apply it when confronted with future problems.

The short time frame within which we worked dictated limited and modest

objectives.

a)

Short run changes have been observed and documented in terms of:

greater work productivity, particularly with respect to team confer-

ence meetings

b)

increased clarity of role expectations plus mechanisms for negotiating

changes in role behavior as they are needed;

c)

greater flexibility in decision-making;

d)

and, more widely shared influence and participation between all team

members

.

19-

IMPLICATIONS FOR HEALTH TEAM OPERATIONS

Based on an uinderstanding of groups in general and our experiences with

health teams working in an urban community, several significant learnings are

beginning to emerge with implications for the delivery of health care using

groups or teams

(1)

Some conscious program which helps team members look, at their par-

ticular goals, tasks, relationships, decision-making, norms, backgroimds and

values is essential for team effectiveness.

a

It is naive to bring together

highly diverse group of people and to expect that, by calling them a team,

they will in fact behave as a team.

(2)

Behavioral science knowledge and techniques, developed in a variety

of non-medical settings are relevant and appear to be transferable to organi-

zations involved in the delivery of health care.

is one such example.

The action research approach

It reflects a methodology and set of values which can

help a team become a self-renewing organism.

team that it treat itself as a patient

—

In some ways, it demands of a

periodically diagnosing its own

state of health, prescribing medication, and subjecting itself to the followup check-ups to insure that the prescription is working.

Although this process

16.

It is ironic, indeed, to realize that a football team spends 40 hours

per week practicing teamwork for the 2 hours on Sunday afternoon when their

teamwork really coimts. Teams in organizations seldom spend 2 hours per year

practicing when their ability to function as a team counts 40 hours per week!

-20-

may require the assistance of a "third party" initially, the "patient team"

can learn to do many of the things itself.

(3)

Ideally, every team member can be a participant in the group's task

and an observer of the group's process.

At a minimum, such capability for

helping teams look at their own working should be built into the training of

team leaders.

(4)

The organizations in which health teams are Inlbedded will need to

develop an internal capability to help groups manage their own process.

Outside resources are appropriate to initiate such activities, but internal

specialists are needed to provide needed continuity, follow-up and reinforcement.

(5)

Programs need to be developed which focus specifically on the prob-

lems of helping people cope with cultural discrepancies whether these be be-

tween a team and its client population or between team members, e.g, the pro-

fesionally based physician and the community based family health worker.

(6)

Certain team members will need particular leadership skills

.

If

nurses are expected to act as team coordinators, they will need special

training.

All team members will need to develop membership skills

,

e.g.,

listening, collaborating.

(7)

Although some of this needed training may be accomplished during

17

individual preparation, some training needs to be done with the team as a

unit

.

In addition, more of this training needs to be goal related , e.g.,

treating a family as an integrated unit as compared to technique related ,

e.g., taking histories, doing EKG's.

(This does not imply that such skills

—

It is clear that existing educational and training institutions

medical

schools, nursing schools, teaching hospitals

will need to bear part of this

responsibility.

In addition to the content areas of psychology, social psychology, sociology, social anthropology and the like, increasing emphasis must

be placed in such areas as group dynamics, organizational behavior, social intervention, and the theory and process of planned change.

~

:

relation to specific

are unimportant - only that they should be learned in

goals).

(8)

The socialization of new team members needs to be examined.

Pro-

grams need to be developed which in fact orient a new family health worker,

for example, to her role as a team member as well as a specialist with par-

ticular skills.

(9)

There is great value in initiating team development activities, of

the kind we described, at the point of a team's formation.

dividuals, develop their own cultures or personalities.

Teams, like in-

In "older teams" a

considerable amount of unfreezing may have to take place before new changes

can be tried.

Early team development efforts would have several distinct

advantages

a)

the period of initial socialization has a very significant effect on

the team's future development

—

early experiences set a very strong tone

which influence future events;

b)

a group can more easily create the kind of culture, norms, procedures

it deems useful if it is starting fresh rather than having to "undo" a long

histoiry of past experiences;

c)

and, perhaps most important, would be the early recognition that the

team really has two equally important tasks

—

to deliver health care and to

continuously work to develop and maintain itself as a well functioning team in

order to improve its services.

-22-

The focus of this paper has been upon the working of existing health teams

in a community setting where entire families are "the patient."

We have

explored some ways in which one might help such a team (1) learn more about its

own "internal dynamics" and (2) use these learnings to continuously improve

the way it functions in delivering health care.

We will, in all likelihood, see an increasing number of models for

delivering health care in which groups of some form play an integral part.

The effectiveness of these groups in accomplishing their tasks will be, in

part, a function of how will they manage themselves with respect to the "process

variables" discussed in this paper.

JAN

»8*»

Wi Z73

Date Due

SI.I-

3

TDtD 003 701 3^b

.,0.7/

liiiiii

3 TOflD

3

TOflO

DD3 b70 3E7

003 701 353

s.^w

liiiiiiiliiili

3 TOflO

003

3 TOflO

003 b70 3M3

3

TOfiO

003 701 2bE

3

TOflO

DD3 b70 350

t.7D

3fl^

^U-7/

<;n-7i

^<,d-7{

003 701 247

3

TOflO

3

TOaO 003 701 37T