TECHNOLOGY AND THE 21ST CENTURY BATTLEFIELD: RECOMPLICATING MORAL THE SOLDIER

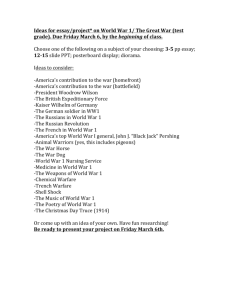

advertisement