Investing in our Collective Future Frances Contreras, Ph.D. Report Development Team:

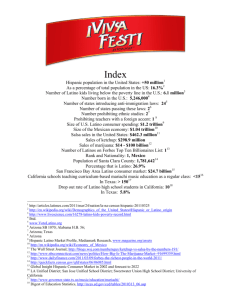

advertisement