Document 11036151

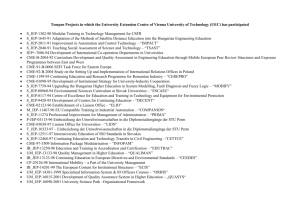

advertisement