Document 11035898

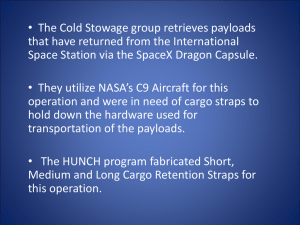

advertisement