Document 11035877

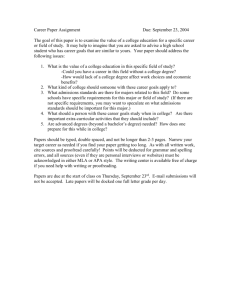

advertisement