Document 11034427

advertisement

HD2 8

Dewey

.M414

^5

ALFRED

ThG

P.

WORKING PAPER

SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT

iTT.plicit

Age Grading:

Organizational TineraMe

BARBARA

March 1983

S.

LAWRENCE

V?P

#1414-83

MASSACHUSETTS

INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

50 MEMORIAL DRIVE

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 02139

Age Grading:

The Implicit Organizational TinetLable

BARBARA

March 1983

S.

LAWRENCE

#1414-83

VfP

I

gratefully acknovjledge the assistance of all those individuals in the

I

Bennix Power Company v.'hose cooperation made this study possible.

would also like to thank Toir, Allen, Richard Bagozzi Lotte Bailyn, and

Edgar Schein of the Sloan School of Kanagement MIT, for their helpful

comments.

,

,

A revised version of this paper to appear in The Journal of Occupational

Behaviour

(forthcoming)

1983

This research was supported by grants

from the Administration on Aging *30 ATO

33/11 and the Office of Naval

,

.

Research, Contract N00014-80-C09C5; NR 170-911.

j

My

MAY

3 1 1983

^

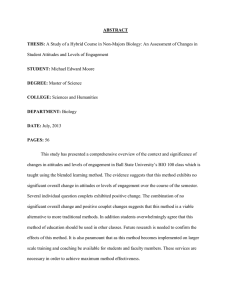

ABSTRACT

The

age

timetable,

timetable

distribution within an organization forms an implicit career

and there is evidence that people use their perceptions of this

to

Questionnaire

determine

data

electric utility.

"behind

time"

whether

were

their

collected

from

careers

are

on or off schedule.

managers (N=488) within a large

The results indicate that managers who see themselves as

their careers have more negative attitudes towards work

in

than other managers, even when their perceptions of being "behind time" are

inaccurate.

more

In

addition, the longer managers remain in the same job, the

likely they are to define themselves as "behind time."

This supports

other research suggesting that lateral moves v;ithin organizations may be an

important

device for managing the normal limitations of upward movement in

managerial careers.

07459c

-1-

Organizations

performance.

from

work

have

often

elaborate

they see everyday on the job.

v/hac

They observe others who are

labelled as successful or unsuccessfu?. and ask, "How am

them?"

and

timetable,

career

doing compared to

The ages of employees in different positions form an

most critical is age.

implicit

I

of comparison involves many factors, but one of the

process

This

appraising

get the most vivid assessments of their

employees

Hov;ever,

for

rr.echanisms

there

is evidence that people use their

of this timetable to determine whether their careers are on or

perceptions

off schedule.

a

study

of managers between the ages of 35 and 39 in two British

companies,

Sofer

(1970:273-274)

In

found an acute sensitivity to the career

clearly aware of where they should be in their

timetable.

Managers

careers

given ages and showed considerable concern if they were behind

at

were

sensitivity

also

evident

Kidder's

schedu].e.

This

description

of

Immediately

after beginning work, these engineers noticed that the careers

of

people

in

(1982:104)

computer engineers in the Data General Corporation.

young

"like

is

mysteriously

ended

me"

at

thirty, suggesting an

age

uncertain future in the organization.

These

expectations

that

show

with

fits

in

to

being well aware of age

employees

are concerned about how

addition

organizations,

their

in

progress

their

this

examples

the implicit career timetable.

The purpose of

study is to examine how perceptions of being on and off schedule with

the career timetable affect employee's attitudes towards work.

To

provide

context

the

for

this

study,

importance of age in social groups are in order.

of

chronological

experiences.

As

aging

makes

a

result,

it

a

few

comments

on the

The unalterable cliaracter

one of the most widely shared of human

strong

expectations

develop

about

age

appropriate

behavior.

allowed

make

assumed

are

be wise and children are

to

People are admonished to "act your age" when

mistakes.

behave in an unexpected manner for someone of their age.

they

an

to

Adults

individual

experience,

social

and

and,

as

a

result,

Age is both

it exerts a

tremendous influence on people's lives.

evidence

Empirical

expectations

underlie

supports

behavior

an

al.

,

that

age

assumptions and

social groups (Eisenstadt, 1955;

1972).

There is consensus that

behaviors that are acceptable at specific ages, and

are

there

all

in

Neugarten & Datan, 1973; Riley et

belief

the

order

which

in

lifetime.

behaviors

these

assumptions

Age

2)

1)

there is

are expected to occur in a person's

and expectations form the clock agaiiist which

people measure their lives.

Are they on-time or off-time with

v.'hat

is seen

as normal progress in life?

Previous

people's lives.

notion

as

suggests

work

that being off-time has a negative impact on

Bernice Neugarten et

al.

(1958), who first described the

being on-time or off-time, found that people who see themselves

of

off-time are more likely to experience crises in their lives than those

who

are

and

middle-aged

on-time.

schedule

had

a

This finding has found support in studies of young men

men

and

women.

Hogan (1978, 1980) found that being off

negative

effect

on the lives of young men.

He observed

demographic patterns of age-specific life events, such as finishing school,

beginning

from

to

work,

and

getting

married.

The results suggest that deviance

normal progress, as defined by those demographic patterns, is related

higher

rates

exploratory

(1980)

found

of

marital

disruption and lower total earnings.

In an

study of men and women making midlife career changes, L£v;rence

that

subjects

who

were on schedule with major family life

-3-

events,

such

and the birth of children, were less likely to

marriage

as

experience career change as a crisis than those who were off schedule.

studies

these

Although

negative impact on people, there are

Because

unlikely

distinctly different ways of being

ahead of schedule is generally perceived in a more positive

being

than being behind schedule,

light

tv;o

People can be either ahead of schedule or behind schedule.

schedule.

off

that being off schedule dees have a

suggest

to have

chese two ways of being off schedule are

Thus, the definition of being

same impact on people.

tlie

or off schedule with age expectations of normal progress should include

on

instead

three,

two,

of

categories:

ahead of schedule, on schedule, and

behind schedule.

expectations

form

organizations,

work

In

that

implicit

an

The

focus

and

the

age-nefined

timetables

develop around career movement.

are apparent in the

These age expectations

but powerful environnient to v;hich members

m.ust

respond.

in this study is on the age expectations of managerial careers,

term

career refers to the set of hierarchical positions managers

might expect to traverse during their tenure with a given organization.

The perception of age expectations that define normal progress through

a

observe

must

their

of

within

career

distribution of the different career levels within

age

the

First, managers

organization, and second, they must make a judgment as to what range

ages

normal

represents

Their

perception

based

on

the

timetable

it

will

progress,

fast

progress, and slow progress.

of their own position on the organizational timetable is

results of these judgments.

carries

Typically,

normal

an organization requires two judgments.

with

it

inherent

Position on the organizational

positive and negative associations.

is assumed that managers who see themselves as younger than

define

themselves

as

-4-

"fast-track,"

or

"water

walkers."

who

see

marooned

on

Conversely,

managers

themselves

as

and

"mobile"

study

this

the

with

associated

example,

for

(1977:133-136),

'"stuck.."

themselves

calls

these

the

older

track

"slow

a

Given

as

two

positive

than

to

ncrn^.al

nowhere."

groups

of

may see

Ranter

managers the

and negative attitudes

ahead of or behind time, the central hypothesis of

being

is that managers who see themselves as ahead of time have more

attitudes towards work than managers who see themselves as either

positive

on time or behind time

.

The Problem and the Method

The Instrument

A

questionnaire was designed to assess managers' age judgments of the

career

timetable within their organization and to examine the relationship

between

in

The questionnaire was developed

their beliefs and work attitudes.

several stages through pre-testing with MBA students (22-30 years old)

middle

managers

Fellows

Sloan

the

in

Program

(35-45

years old)

,

,

and

executives

in the Senior Executives Program (45-60 years old) at the Sloan

School

Management,

of

MIT.

An additional pre-test was conducted with a

small group of managers within the company eventually studied.

In order to obtain managers'

v;ere

their

the

asked

to

judgment

give,

for

perceptions of the career timetable, they

each hierarchical level in their organization,

of 1) the typical age of individuals in that level, and 2)

age range of individuals in that level.

responses

suggest

that

In the follov;ing example,

the

Supervisors are between the ages of 25 and 68 and

typically 36 years old.

-5-

:

THE r>PICAl AGE AND ACE aANCK C? KA'.AUiSS

Give.

1.

ny fcrcepHon Is

In

1:1::::

I-}-^.

l-i—^-t—^l-fi

;

i

i

:

ZKCW lEO

lilf

..-

i

-t-t-i-t-i-i.

.

•-

to

•

I

,

•

•

•

T

•

.

•

•

:

;

1

:

-*-

t

t

I

:

70

60

perceptions of how far off scnedule they

are in their organizational careers, managers'

judgments of the typical age

own career level were subtracted from their

their

T

•

iO

In order to measure managers'

for

TOSIT.'OI.'S.

Superv is or.' =r€

V'.h'.

^'

30

?0

HXDIKC

ov.t.

age.

Thus, the

individual age discrepancy of a 40 year old, first level manager who judged

the

for his or her level to te 52, would be eight.

age

typical

this

measure

with

their

Although

identifies the extent to v;hich managers' ages are discrepant

perceptions of what is typical for their career level, it does

not identify directly whether managers perceive themselves as ahead, on, or

behind

However, the data show that people in the organization that

time.

was studied believe the average time in every career level is three to four

years.

two

Thus,

years

of

seems reasonable to expect that managers who are within

it

what

themselves

identify

believe

they

as

typical for their own career level

is

time, and that managers who are seven or more

on

years younger than what they believe is typical, roughly two career levels,

themselves

identify

as

ahead

of

In view of recent evidence that

time.

people

continue to hope that things will get better even after the average

length

of

progress)

three

,

time

as

levels

— seems

behind

time.

therefore into three groups:

between

-2

individual

advances

career

passed (Bailyn, 1982, work in

has

somewhat larger age discrepancy of ten years or more

a

career

themselves

for

and

age

+2

were

reasonable

The

1)

to

population

managers

identify

of

managers

was

— almost

who

see

divided

managers with an individual age discrepancy

classified

as

on

time;

2)

managers with an

discrepancy less than -7 were classified as ahead of time;

-6-

and

managers with an individual age discrepancy of greater than +10 were

3)

Managers in the two inbetween categories (-3 to

classified as behind time.

-6,

to +9) were eliminated from the analysis.

+3

Given the shared belief

that

age differences between career levels are around three to four years,

the

psychological

meaning

discrepancies

age

of

in

these

inbetween

categories is more tenuous.

data

The

suggest

managers

who

time

their

in

there

of

managers

are

on

careers.

direct

no

is

or

categories

three

identify

off

However, two cautions should be

measure to confirm managers' actual

time; therefore, it is possible that some

accurately classified.

not

accurately

as either on time, ahead of time, or behind

organizational

being

feelings

the

themselves

see

First,

noted.

that

Second, the boundaries defining

the on and off time categories are based on data from the organization that

was studied and are not necessarily generalizable to other organizations.

questionnaire

The

questions

based

are

Oldham,

1980)

Schein,

1980),

questions

success

motivation

anchored

final

(#7-#9)

five-point

Two

the Job Diagostic Survey (Kackman &

from

come from the MIT Alumni Survey (Bailyn &

new

to

this

questionnaire.

Two of the

#6)

.

questions inquire about subjects' feelings of

These questions use six-point scales, with responses

of

how strongly subjects agree or disagree.

The

questions elicit information about subjects' work orientation

as

organization

on v;ork attitudes.

their work and two questions examine subjects' work

in

#4)

statements

to

are

Two

#2).

(#5,

tliree

,

three

questions

nine

respondents about their satisfaction with current career or

(#1,

(#3,

items

questions

and

ask

occupation

on

four

,

includes

measured

for

scales,

by

their

stated

probability

changes in various aspects of work.

with

of

leaving

the

These questions use

responses anchored to statements of how likely a

-1-

inducement

given

are

years.

five

v/ithin

sufficiently

organization

HigJi

scores on these questions suggest that managers

oriented

work,

to

order

in

to influence the subject to leave the company

be

v.'ould

meet

would

they

that

their

needs

leaving the

consider

for

work

particular

a

environment.

The Sample

United

northeastern

States.

after

company

the

with

organization (r=.84)

utility

electric

this

in

the

The Bennix Power Company (not its real name)

Traditionally, people come to work in

.

This is

The average age of exempt employees is 45

and the average tenure is 20 years (range=C-45)

(range=22-65)

in

large

high correlation between age and number of years tenure

in

the

a

finishing school and remain until retirement.

reflected

careers

in

established organization.

is an old,

the

conducted

was

study

The

company

have

Level

eight

levels:

Level

1

.

Managerial

is a first level

includes the Chief Executive Officer &

supervisory

position

President.

The time-honored route in management is to "move up the ranks"

requiring

positions

from

and

8

engineering

backgrounds,

a slow process in an

organization such as this.

questionnaire

The

employees.

was distributed through company mail to all exempt

A stamped envelope was enclosed with each questionnaire, to be

returned to HIT through US mail.

Company

concerns

prohibited

One follow-up mem.orandum was distributed.

extensive follow-up procedures.

Forty-seven

percent (N=488) of all exempt employees returned the questionnaire.

demographic

years

Actual

data were obtained on the age, sex, functional area, number of

tenure with the company, and hierarchical level of all employees.

comparison

of

these

values

v;ith

A

values obtained from respondents to the

-8-

questionnaire shov;s that the sample han demographic characteristics similar

to those of the population.

Findings

division

The

Thirty-three

ahead

39%

and

percent

(N=82)

perceive

(N=95)

subsample

a

groups based on

245

of

managers.

these managers perceive themselves to he

of

themselves

orientation,

differences

attitudes

produced

three

to be behind schedule.

All the managers

organization show relatively high levels of work satisfaction

this

work

into

sample

28% (N=5S) perceive themselves to be on schedule, and

schedule,

of

within

discrepancies

age

individual

original

the

of

thus

between the groups.

are

findings

the

are

This means that groups with more negative

necessarily dissatisfied.

not

based on a comparison of

It only means that they are

less satisfied than other groups.

This

work

analysis

examines the global pattern of responses to aspects of

satisfaction

and work orientation.

The items presented here are not

meant to represent all possible components of these attitudes towards work.

For

question,

each

managers

The

responded

who

Kruskal-Wallis

ranking

the

of

T

If

differences

between

Table

the

nine

1

"percent

in

who

agree" represents the fraction of

the two highest categories for that question.

reported

each

for

table tests whether or not the

responses of the three groups is the same across all nine

questions.

1980:229-239)

the

differences

pairs

for

of

the

groups

three

are

groups

also

are

significant,

examined

(Conover,

.

shows

questions.

groups (p<.00l).

the percentage of each group that agreed with each of

This table shov;s clear differences between the three

In all cases except for one,

-9-

people who see themselves as

TA3LL 1

Work Attitudes By Individual Age Discrepancy

PERCENT WHO AGREE

Ahead of Time On Time Behind Time

N=95

N=68

N=82

Work Satisfaction:

1) Generally speaking, I am very

satisfied with my current:

career choice.

2) I wish I v.'ere in a comple-cely

different occupation.^

3) Generally speaking, I am very

satisfied with my career progress.

4) I am considered a successful

person in this company.

5) I like to think about my work

even when off the job.

6) My only interest in my job is to

get the money to do the other

things I want to do.*

78

79

69

58

ahead

time are more satisfied vjitn and mere oriented towards work than

of

who

those

either

themselves

see

as behind time

themselves

as

on

time (p<.001) or those

In addition,

(p<.001).

support

that managers

hypothesis

the

see

managers who are on time

have more positive attitudes than those who are behind time.

clearly

vjho

v;ho

These results

perceive themselves as

of time have more positive attitudes towards work than those who see

ahead

themselves as either on time or behind time.

However,

related

to

perceive

him

herself

or

organization

this

in

that,

shcv;s

a person's perception of age discrepancy is

It is difficult for a 55 year old manager

his or her own age.

to

possible

definition,

by

Table

to be ahead of time at that age.

2

there is a strong relationship between the ages of

fact,

in

ahead of time, simply because it is not

as

managers

and

their

managers

get

older, they are more likely to perceive themselves as behind

individual

discrepancy

age

{1>

= .1BB,

p<.00l).

As

time.

The literature suggests that job satisfaction is positively related to

age

and

number

the

(Andrisani et

For

this

managers

reason,

is

groups.

age-related

varies

relationship

the

themselves

surprising

This

has

worked in an organization

because

to

observed in Table

1,

ahead

time

be

of

suggesting that

are

the most

these managers are the youngest of the

unexpected relationship may be explained by a second

observation

about

work, which is that the centrality of work

the life span (Evans & Bartolome, 1981; Schein, 1978).

over

managers

who

involved

with

oriented.

person

a

1977; Janson & Kartin, 1981; Van Maaiien & Katz, 1976).

,

perceive

v.'ho

satisfied,

three

al.

years

of

As

are

just

beginning

careers

and

Young

families tend to be more

their work than older managers who often become more family

children

grow older and the major career goals have either

-11-

TABLE 2

Age By Perceptions of Being On or Off Time

Ahead of

Age

<

35

35-50

>

Tin-.e

Behind Time

(N)

%

(N)

%

(N)

53

(36)

11

(9)

5

(5)

47

(32)

57

(47)

28

(26)

(0)

32

(26)

67

(64)

100 (82)

100

(95)

100 (68)

X^ = 108.9

t

=

df = 4

p < .001

P

<

achieved

changes

On

%

50

Total:

been

Tinie

not achieved, the pattern of work-family accommodations

or

(Bailyn,

.788

-001

1978).

In order to see vjhether the centrality of work is

a possible explanation for the observed relationship between perceived time

categories

work

and

a single age group, managers between the

attitudes,

ages of 35 and 50, was examined.

Excluding

the

average

actual

Thus,

the

their

being

ages

the

career

for

all

career levels fall between 47 and 54.

on or off time is probably most critical for managers between

with

people

organizational lives.

major

ages

of 35 and 50 who are facing knov.'ledge of the probable outcome of

constraints,

make

Chief Executive Officer and President in this company,

Job

the

at

company.

In addition to perceived organizational

this age also face age expectations outside their

The expectation is that if people wait any longer to

changes,

they will be perceived as "too old" and will be

-12-

Even if they have no intention

unable to find other work (Lawrence, 1980).

of

leaving, 35 to 50 year-old managers in this company must face

actually

realisation

the

the issue of "How

reasons,

to

between

the

three

are

For these

limited.

am doing in my career" is likely tc be highly

minimizing the expected differences

thus

It is possible that dissatisfied employees in

groups.

have already adapted to staying.

remain

probably

category have already left the company, in which case, those who

age

this

I

individuals,

these

salient

options

future

that

Hov;ever, the low turnover in this

organization suggests that this would have little effect on this sample.

Table

and

35

shows the work attitude scores of managers between the ages of

3

the

(p<.Ol),

the three groups are still significantly different

Although

50.

Those who see themselves as on

differences have diminished.

time are now similar to those who see themselves as ahead of time (p=n.s.).

On four of the nine questions, on time managers are more satisfied v;ith and

oriented towards work than ahead of time managers.

more

to

note,

that,

themselves

ahead

as

progress, and

career

by

even

others

and

more

negative

Thus,

centrality

groups,

of

people

2)

are still

1)

about

more satisfied

vjith

v?ho

see

their own

more likely to feel they are considered successful

However, despite the fact that on

of time groups are similar,

ahead

p<.Ol).

time

of

two groups are similar, people

the

those who are on time.

than

tim.e

though

It is interesting

the behind time group remains

work then either group on all nine questions (p<.01;

it

appears

work

using

although

that

age

controlling

for the probable

reduces the differences between the three

who see themselves as behind time are still less satisfied

with and less oriented towards their work.

One

managers

possible

are

explanation

for

these

results

is

that

behind time

really behind schedule and thus have a legitimate reason for

-13-

v;orl'v

TABLE 3

Attitudes By Individual Age Discrepancy

Subsample: Ages 35-50

PERCENT WHO AGREE

Ahead of Time On Tins Behind Time

N=26

N=47

N=32

Work Satisfaction;

1) Generally speaking, I am very

satisfied v;ith my current

career choice.

2) I wish I were in a completely

different occupation.*

3) Generally speaking, I am very

satisfied with my career progress.

4) I am considered a successful

person in this company.

5) I like to think about my work

even when off the job.

6) My only interest in my job is to

get the money to do the other

things I want to do.*

69

84

70

35

:

their

the

actual age distribution for each career level.

deviation

standard

within

actually

considered

older

deviation

Thus,

being

one's

own

mobility

younger

managers

schedule,

the

The actual career schedule of maraoers was measured using

feelings.

level.

with

actual

schedule

It

company

career

is

does

and

means

not

schedule,

47

deviation

managers

considered

are

the

of

more

average are

than one standard

actually behind schedule.

being older than the average age for

mean being behind the normal pattern of

(e.g. Rosenbaum,

age

actually behind schedule.

the

standard

one

average

than

behind

than average are considered actually ahead of

schedule,

on

Managers more than one

1979a, 1979b).

Using this measure of

none of these 35 to 50 year-old managers is

The youngest average age for any career level in

with a standard deviation of

6,

meaning that managers

must

be over 53 before they are really behind schedule.

many

of the managers in each perceived time category are actually ahead of

Table 4 shov;s how

schedule, actually on schedule, or actually behind schedule.

TABLE 4

Actual Schedule by Perceived Schedule

Subsample: Ages 35 - 50

ACTUAL SCHEDULE

PERCEIVED SCHEDULE

Ahead of Time

On Time

Behind Time

%

(N)

%

(N)

%

(N)

Ahead of Schedule

50 (16)

21

(10)

4

(1)

On Schedule

50 (15)

79

(37)

96 (25)

(0)

(0)

(47)

100 (25)

Behind Schedule

Total

(0)

100 (32)

-15-

100

The lack of accuracy of perceptions in t^e group that perceives itself

as

time

behind

groups.

is

particularly

when

marked

compared to the other two

of those who see themselves as ahead of time and 79 percent

lialf

of those who see themselves as on time are accurate in their perceptions.

The

clearly

managers

judgments

of

are

based

not

see

actual

the

on

their

However,

organization.

who

as behind schedule

themselves

age

distribution

within

the

negative feelings of work satisfaction and

work orientation may be the indirect result of these age distributions.

In

other words, work attitudes may be explained by where managers actually are

in

careers rather than where they think they are.

their

group has more negative attitudes because almost all of this group is

time

actually

and all m.anagers who are actually on schedule have

schedule,

on

negative attitudes regardless of their perceptions.

more

all

Thus, the behind

35-50

m.anagers

who

actually

are

on

schedule

Table

compared

5

includes

by

their

perceptions of being on or off time.

three

In

ahead

time {p=n.s.), and for the first time, the behind time group has

of

though

scores

the

actually

being

the

groups,

who

work

perceptions

attitudes,

than

attitudes

positive

more

and

the nine questions, those who see themselves as on time

more positive attitudes towards work than those who see themselves as

have

those

of

on

on

time group on two questions, even

nearly identical.

are

schedule

behind

the

the differences between these three

reduces

group

time

is still consistently more negative than

see themselves as ahead of time.

orientatj.on

thus

effect

appear

to

Feelings of work satisfaction

be related to the joint effect of

Although perceptions do appear to influence work

and reality.

the

However, despite the fact that

of

these perceptions seems to be mitigated by the

manager's actual position on the organizational career timetable.

-16-

TABLE 5

Work Attitudes By Individual Ags Discrepancy

Subsample: Ages 35-50 and Actually On Schedule

PERCENT WHO AGREE

Ahead of Time On Time Behind Time

N=25

N=16

N=37

Work Satisfaction:

1) Generally speaking, I am very

satisfied v;ith my current

career choice.

2) I wish I were in a completely

different occupation.*

3) Generally speaking, I am very

satisfied with my career progress,

4) I am considered a successful

person in this company.

5) I like to think about my work

even v;hen off the job.

6) My only interest in my job is to

get the money to do the other

things I want to do.*

69

81

70

32

The findings discussed to this point suggest that managers

off-time

are

they

aspects

their

of

This

v.'ork.

believe

timetable are more negative towards

career

the

is intriguing because, without exception,

perceptions are inaccurate.

managers'

these

with

v;ho

A remaining question then is

how people make the age judgments that result in these negative feelings.

who see themselves as behind schedule may have had different

Managers

paths than those who see themselves as either ahead or on time.

career

by Bailyn

described

plateaued

been

(1979)

years

for

,

As

35-50 year old middle managers may either have

current position after rapid career

their

in

their careers, or they may have achieved their current

movement

early

position

only recently after slov; movement throughout their organizational

in

Managers

tenure.

with

others

they

see

Martin,

v;ho

similar ages and feel behind schedule and "deprived" when

of

in their comparison group begin new jobs

managers

1981)

have not changed jobs recently may compare themselves

feelings

These

.

(Adams, 1965;

of deprivation could then result in more

negative work attitudes.

data

The

paths

of

years

subjects

recent

these

behind

be examined.

cannot

However, the number of

been in their current jobs provides an indication of

movement.

as

on

time

time category.

needs

individuals

Table

6

shows

that,

in fact, people who see

schedule are much more likely to have been in their

jobs longer than four years than those who see themselves as ahead

current

or

study are cross-sectional, thus the entire career

this

have

career

themselves

of

in

to

be

— even

when those groups are controlled for age and actual

Although these findings are suggestive, additional research

conducted to understand the process by which people make and

then interpret age judgments of managerial careers.

-18-

TABLE 6

Number of Years in Current Job

Subsample: Ages 35-50 and Actually on Schedule

PERCEIVED SCHEDULE

NUMBER OF YEARS

IN CURRENT JOB

Ahead & On Time

%

(N)

Behind Time

%

(N)

0-4

Years

61

(30)

22

(5)

5 +

Years

39

(19)

78

(18)

100

(49)

100

(23)

Total;

Summary and Discussion

These

themselves

data

are

ahead

as

towards their

support

v.'ork

of

original

the

hypothesis

that managers

v;ho

see

are more satisfied with and more oriented

time,

than other managers.

In general, managers v;ho feel they

ahead of time have more positive work attitudes than managers who feel

they are on time, and mianagers who feel they are on time have more positive

work

attitudes

than

those

who

feel they are behind time.

However, the

relationship betv;een individual age discrepancies and work satisfaction and

work

orientation

behind

time

time

not linear.

The

Although managers who see themselves as

always the most negative group, the ahead of time and on

groups have similar attitudes

schedule.

may

are

is

comparatively

v;hen

controlled for age and actual time

negative attitudes of the behind time group

be explained by the joint effect of perceptions and actual position on

the organizational timetable.

-19-

judgments of whether they are on or off time frequently are

Managers'

of

the

judgments nay be related to the recent career movement

These

inaccurate.

manager.

are more likely to see themselves as ahead of

Managers

on time if they have started new jobs within the last four years.

time

or

This

suggests

that relative deprivation is a possible explanation for the

age judgments and comparative dissatisfaction of the behind time group.

are two major implications of this study.

There

suggest

researchers

are

demography,

age

distributions,

single

the

critical

also

factor

referred

to

explaining

in

as age

some

outcomes (Pfeffer, 1982), these distributions alone clearly

organizational

not sufficient for understanding the relationship between age and work

are

Both individual perceptions and demographic information on age

attitudes.

be considered.

must

as

that

First, although some

Second, if it is true that managers define themselves

behind schedule as a result of infrequent job moves

can

alleviate

some

in

itself

rather

determining age judgments.

et

This

al.

,

has

1980)

then organizations

of the comparatively negative feelings experienced by

this group by providing alternative job opportunities.

movement

,

movement is what is critical in

upward

than

It is possible that

Lateral moves (Hall, 1976; Schein, 1978; Stoner

may be just as effective an intervention as vertical moves.

significant

implications

in

a

time

v;hen an

aging work force

decreases the opportunity for upward mobility within organizations.

-20-

REFERENCES

S.J.

Inequity in social exchance.

In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances

Experimental Social Psycnology

New York: Academic Press, 1965,

267-299.

Adams,

in

.

Andrisani, P.J., Appelbaum, E., Koppel, R., & Mi'ljus, R.C. V/ork attitudes

Evidence from National Longitudinal

and

labor market experie n ce;

Surveys

Center

for

Labor and Human Resource Studies, Temple

University, Pennsylvania, 1977.

.

Bailyn,

L.

Accommodation of work to family.

New York: Harper

(Eds.), v;orking couples.

In R.

& Row,

Rapaport & R. Rapaport

1978, 159-174.

L.

(in

collaboration with E. Schein) Living with technology!

Bailyn,

Issues at mid-career.

Massachusetts: MIT, 1980.

,

Bailyn,

L.

success?

Taking off for the top: How much acceleration for career

Management Review, 1979, 68(1), 18-23.

Conover, W.J.

Practical

John Wiley, 1980.

nonparametric

statistics (2nd Ed.).

New York:

Eisenstadt, S.N.

From generation to generation: Age groups and social

structure.

London: Free Press of Glencoe, 1956.

Evans,

P.,

&

Bartolome,

Books, 1981.

F.

Hackman,

J.R.,

&

Oldham,

Addison-Wesley, 1980.

Hall, D.T.

Must success cost so much?

G.R.

Careers in organizations.

Work

redesign

.

New York: Basic

Massachusetts;

California: Goodyear, 1976-

Hogan, D.P.

The transition to adulthood as a career contingency.

Sociological Review, 1980, 45, 261-275.

-21-

American

The variable order of events in the life course.

D.P.

Sociological Review, 1978, 43, 573-586.

Kogan,

Martin,

P.,

f.

Janson,

satisfaction and age.

1981.

Men

R.M.

Kanter,

and

American

Notes on the quality of vjorking life: Job

Unpublished paper, Pennsylvania State University,

J.K.

women of the corporation

.

New York: Basic Books,

1977.

T.

Kidder,

1981.

The soul of a new machine

B.S.

1980, 21(4)

Lawrence,

,

.

Boston: Little, Brown and Company,

Sloan Management Review

The myth of the midlife crisis.

35-49.

,

Martin, J. Relative deprivation: A theory of distributive injustice for an

Cummings & B.K. Staw (Eds.),

In

L.L.

era of shrinking resources.

Connecticut: JAI Press,

Research in Organizational Behavior, Volume 3

1981, 53-107.

.

Sociological perspectives on the life cycle.

B.L., & Datan, N.

Life-span developmental

(Eds.),

Baltes and K.W. Schaie

New

York: Academic Press,

socialization

Personality

and

sychology;

p

53-71.

1973,

Neugarten,

In

P.B.

.

Age norms, age constraints, and

Neugarten, B.L., Moore, J.W., & Lowe, J.C.

In B.L. Neugarten (Ed.), Middle age and aging: A

adult socialization.

Illinois: Univers:^ty of Chicago, 1968,

reader in social psychology

22-28.

.

Some consequences of organizational demography: Potential

Pfeffer,

J.

In J.G. March

impacts of an aging v;ork force on formal organizations.

Academic Press, 1981,

New York:

Aging and social change

(Ed.),

291-329.

.

Johnson, J., and Foner, A. (Eds.), Aging and society, Volume

Russell Sage

New York:

sociology of age stratification

III;

A

Foundation, 1972.

Riley,

M.W.,

.

Organizational career mobility: Promotion chances in a

Rosenbaum,

J.E.

corporation during periods of growth and contraction. American Journal

of Sociology, 1979a, 85, 21-48.

-22-

Tournament mobility: Career patterns in a corporation.

J.E.

Rosenbaun,

Administrative Science Quarterly, 1979b, 24, 220-240.

Career dynamics: Matching individual

E.H.

Scnein,

Massachusetts: Addison-V/esley 1978.

nesds.

and organizational

,

mid-career: A study of British managers and technical

C.

Men

in

specialists.

Great Britain: Cambridge University, 1970.

Sofer,

Warren,

E.K.,

Christensen, H.K.

J.A.F.,

Ference,

T.P.,

&

New York: Center for Research in Career

Managerial career plateaus

Development, Columbia University, 1980.

Stoner,

.

Van

Maanen,

J.,

considerations

601-616.

Individuals and ther careers: Some temporal

Katz, R.

Personnel Psychology 1976, 29,

for work satisfaction.

&

,

-23-

7§k3 US^tV

Date Due

Lib-26-67

HD28.IVI414 no.l414-

83

Lawrence, Barb/Age gradinq

74590.1,,....

lBasemen T

3

.D*BKS

TQflO

.

002

O0l61869

3flfl

MOO