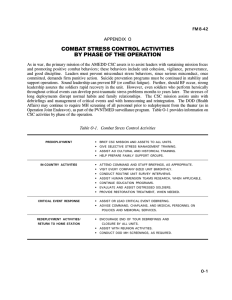

Chapter 10 COMBAT STRESS CONTROL IN JOINT OPERATIONS

advertisement