Out of Bounds?

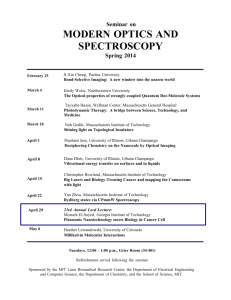

advertisement