Storytelling on the Margins:

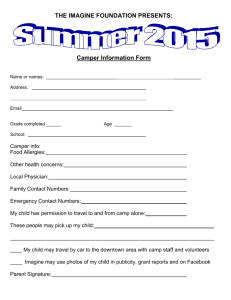

advertisement