Document 11012120

advertisement

THE BAER-SPECKER GROUP

Eoin Coleman1

The Baer-Speker group, P, is the group of funtions from the

natural numbers N into the integers Z. While P is very easy to

dene, it is the soure of a wealth of problems, some of whih have

only reently been solved. The aim of this paper is to present

an introdutory aount of old and new results about P, and to

explore some of the onnetions of this group with other areas of

mathematis, in partiular with the real numbers, innitary logi,

and ombinatorial set theory.

Introdution

The Baer-Speker group P is an innite abelian group under the

addition

(f + g)(n) = f (n) + g(n)

for n 2 N. P ontains the subgroup S, the diret sum of ountably

many opies of Z. In the literature, P is also denoted ZN , or Z! .

Sine all the groups onsidered in this paper are abelian, it will

save spae to adopt the onvention that the term group is short

for abelian group. The textbooks [20℄ and [22℄ are good referenes

for innite abelian group theory. We use the symbols !, !1 , and

2! to denote the ardinal numbers of the natural numbers N, the

rst unountable ardinal, and the ardinal number of the real

numbers R, respetively. For example, P has ardinality 2! , and

S has ardinality !.

1

I am very grateful to the organizers of the Irish Mathematial Soiety Conferene in September 1997 for the opportunity to read a shorter

version of this paper to the partiipants.

9

10

IMS Bulletin 40, 1998

There are four setions in the paper. The rst resumes some

basi material on P; the seond looks at a reently disovered onnetion relating slender subgroups of P to ertain ardinal invariants of the real numbers. In the third setion, some logial aspets

of P are explored. The nal setion is about the omplexity of the

lattie of subgroups of P. Sine the material overed in the paper

is diverse and sattered aross dierent domains, I have not given

many proofs, hoping that the bibliography will enable the reader

to follow themes in more depth.

1. Basis

The struture of innite free groups is relatively lear (see, for

example, [22℄): for eah innite ardinal , there is exatly one

free group of ardinality on generators (up to isomorphism).

So an obvious initial question in the study of P is to determine

how it stands in relation to freeness: is P free?

Denition A group G is free if G is (isomorphi to) a diret sum

of opies of Z.

For example, P has a free subgroup S.

Theorem 1.1 (Baer [1℄) The group P is not free.

We shall dedue this theorem from a stronger assertion below

involving the notion of {freeness.

Denition Suppose that is an innite ardinal. A group G is

{free if every subgroup H G having less than elements is

free.

Every free group is {free for every ardinal , sine subgroups of free groups are free; if < , then {freeness implies {

freeness. Questions about whether {freeness implies {freeness

for < are highly non-trivial and have stimulated one of the

most important researh orientations in innite abelian group theory, leading for example to Shelah's singular ompatness theorem

[7, 25, 20℄ and independene results in set theory [30℄. Sine in

general {freeness is weaker than freeness, we an rene the initial

question about the non-freeness of P and ask whether there are

any ardinals for whih P is {free. Reall that !2 is the seond

unountable ardinal, the ardinal suessor of !1 .

The Baer-Speker Group

11

Proposition 1.2 The group P is not !2 {free.

We need to nd a non-free subgroup of P whih has ardinality !1 . Let p be a xed prime number, and take a pure

subgroup H of ardinality !1 ontaining S and suh that every

element (n1 ; n2 ; : : :) of H has the property that the tail is divisible by arbitrarily high powers of p: (8m)(9r)(8k > r)(pm jnk ).2

Then the quotient group H=pH is a vetor spae over Fp , the nite

eld of p elements. It follows that H is not free, for if H were free,

then H=pH must have dimension (and hene ardinality) !1 ; but

every oset of H=pH ontains an element of S, and hene H=pH

has ardinality at most jSj = ! {a ontradition. So H is not

free.

We an use Proposition 1.2 to improve exerise 19.7 of [22℄:

Proof:

Corollary For every unountable ardinal , there exists a nonfree !1 {free group of ardinality .

Proof: For example, the group < H , the diret sum of opies

of the group H in the proof of Proposition 1.2, will work.

Proposition 1.2 implies Baer's theorem, sine H is a nonfree subgroup of P. However, it leaves open the question whether

ountable subgroups of P are free, i.e. whether P is !1 {free.

Theorem 1.3 (Speker [42℄) The group P is !1 {free.

Proof: This is a well-known result and a full proof is given in

the standard referene textbooks [20, 22℄. It rests on Pontryagin's

Criterion: a ountable group is free if and only if every nite rank

subgroup is free. We shall give a proof of this riterion using logi

in setion three. The proof of Theorem 1.3 proeeds as follows:

every nite rank subgroup of P is embedded in a nitely generated

torsion-free diret summand of P, and hene is free; so if G P is

ountable, then every nite rank subgroup of G is free; now apply

Pontryagin's Criterion.

To lose this setion, let us introdue another type of \loal"

freeness whih has been intensively studied: a group G is almost

free if G is jGj{free (jGj is the number of elements of G), i.e. every

Or: let H be an elementary submodel of the p-adi losure of S in P

of ardinality !1 ontaining S. H exists by the Downward LoewenheimSkolem Theorem of rst-order logi.

2

12

IMS Bulletin 40, 1998

subgroup of G of smaller ardinality than G is free. Is P almost

free?

Corollary 1.4 P is almost free if and only if the Continuum

Hypothesis (CH: 2! = !1 ) holds.

If the Continuum Hypothesis is true, then P is almost free if P

is !1 {free, whih is true by Theorem 1.3; if the Continuum Hypothesis is false, then the subgroup H in Proposition 1.2 is a non-free

subgroup of ardinality !1 < 2! = jPj and so P is not almost

free. Thus one annot deide whether P is almost free or not on

the basis of ordinary set theory (ZFC).

One trend in the study of {freeness has been to try to nd

equivalenes between the algebrai and set-theoreti denitions.

In light of Corollary 1.4, it might be interesting to know whether

there are algebrai properties ' and suh that:

(1) P has almost ' i the weak Continuum Hypothesis (wCH:

2! < 2!1 ) holds;

(2) P has almost i Diamond holds.

Diamond is a stronger form of the Continuum Hypothesis CH.

One way to state CH is as a list of guesses A for the subsets of

N:

(9fA : < !1 g suh that

(8X N)(f : X = A g is a stationary subset of !1 )):

A stationary subset of !1 is large: it intersets every losed

unbounded subset of !1 (in the order topology) non-trivially. In

other words, the Continuum Hypothesis says that there is a list of

length !1 whih predits orretly every subset of natural numbers

a large number of times. What about subsets of !1 ? One annot

hope for a list of length !1 whih would predit orretly every

subset of !1 , sine there are 2!1 subsets of !1 and 2!1 > !1 .

But perhaps one might be able to predit orretly just the initial

segments of subsets of !1 . Diamond asserts that there is a list of

!1 guesses A for the initial segments of subsets of !1 and these

guesses are orret on a large subset of !1 . Formally, Diamond

The Baer-Speker Group

13

states:

(9fA : < !1 g suh that

(8X !1 )(f : X \ = A g is a stationary subset of !1)):

A more detailed explanation of this type of predition priniple

an be found in the standard textbooks on set theory [26℄ and

[29℄.

2. P and the real numbers R

We start this setion by looking at some ardinal invariants of the

real numbers R. Reent researh has unovered rather surprising onnetions between these invariants and the size of ertain

subgroups of P.

Denition (1) The additivity of measure, add(L), is the smallest number of measure-zero subsets of R whose union is not of

measure zero.

(2) The additivity of ategory, add(B), is the smallest number

of rst ategory subsets of R whose union is of seond ategory

(not of rst ategory).

(3) The ardinal d, the dominating number, is dened as:

minfjDj : D is a subset of NN and

(8g 2 NN )(9f 2 D)(g(n) f (n) for all but nitely many n)g:

(4) The ardinal b, the bounding number, is dened as:

minfjB j : B is a subset of NN and

(8g 2 NN )(9f 2 B )(g(n) < f (n) for all but nitely many n)g:

The ountable additivity of Lebesgue measure and the Baire ategory theorem imply that add(L) and add(B) are both at least

!1 . And they are also at most 2! . It is immediate too that

!1 b d 2! .

14

IMS Bulletin 40, 1998

The reason why the dominating and bounding numbers are

alled invariants of the reals is that the irrationals are homeomorphi to the topologial spae NN when NN is given the produt

topology and N has the disrete topology.

We shall need one other invariant whih is alled the pseudointersetion number. A family F of subsets of N has the strong

nite intersetion property (SFIP) if the intersetion of every

nite subfamily is an innite set. For example, the family of onite subsets of N has the SFIP. A set A is almost ontained

in a set B if A n B is nite.

Denition The ardinal p is

minfjF j : F is a family of subsets of N suh that F has

the SFIP but there is no innite set whih is almost

ontained in every member of F g:

It is an instrutive exerise to show that !1 p 2! .

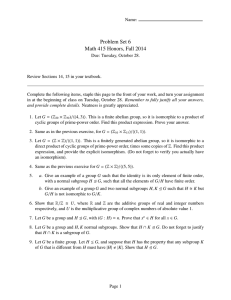

These ardinals are related as in the following piture, part of

the Cihon diagram (exept for the ardinal p). An arrow relation

! means :

2!

6

d

6

b

6 Miller [32℄

add(L)

6

!1

- add(B)

6 Martin and

Bartoszynski [2℄,

Raisonnier and Stern

[36℄

-

Solovay [31℄

p

The Baer-Speker Group

15

Some of the earliest results on the ardinal invariants of the reals

are due to Rothberger [37℄. The disovery of Martin's Axiom

in 1970 stimulated renewed interest in these and other invariants. A fuller aount of the area whih has been studied in great

depth by mathematiians sine the 1970's is available in the artiles by van Douwen [13℄ and Vaughan [44℄. More reent work has

revealed links between ardinal invariants and quadrati forms:

several of these invariants determine how large orthogonal omplements there are in a quadrati spae. This researh (on Gross and

strongly Gross spaes) is surveyed in the paper [43℄. The bounding number b also appears in reent work (in funtional analysis)

on metrizable barrelled spaes [38℄.

To explain the onnetion of ardinal invariants with the BaerSpeker group P, we shall introdue one further denition.

Denition (Los). A group G is slender if whenever is a homomorphism from P into G, then (en ) = 0 for all but nitely many

n, where en is the element of P that has 1 at the n{th o-ordinate

and 0 everywhere else.

There are several important equivalent haraterizations of

slender groups whih we insert here for the sake of ompleteness

and as an aid to intuition.

Theorem 2.1 (Nunke [33℄, Heinlein [24℄, Eda (1982, see [20℄))

The group G is slender if and only if G does not ontain a opy

of the rationals Q, the yli group of order p Z(p), the p-adi

integers Jp , or P;

equivalently, every homomorphism from P into G is ontinuous,

where G and Z are given the disrete topology and P the produt

topology;

equivalently, for any family fGi : i 2 I g and homomorphism from i2I Gi to G, there are !1 -omplete ultralters D1,: : : , Dn

on I suh that

(8g 2 i2I Gi )(if the support of g; fi 2 I : g(i) 6= 0g;

does not belong to Dk (1 k n); then (g) = 0):

Corollary 2.2 Every !1 {free group whih does not ontain P is

slender.

16

IMS Bulletin 40, 1998

Examples The group Z is slender; every free group is slender. P

is not slender (Speker [42℄). Subgroups and diret sums of slender

groups are slender.

Speker's proof that P is not slender works for many other

subgroups of P whih exhibit the Speker phenomenon. But

these subgroups all have ardinality 2! .

Denition (Eda [15℄, Blass [8℄) (1) A subgroup G of P exhibits

the Speker phenomenon i G ontains a sequene fgn : n 2

Ng of linearly independent elements suh that whenever is a

homomorphism from G into Z, then (gn ) = 0 for all but nitely

many n.

(2) The Speker-Eda number, se, is dened as:

minfjGj : G P exhibits the Speker phenomenong:

Corollary 2.3 !1 se 2! .

Theorem 2.4 (Eda [15℄.) (1) CH implies se = !1 .

(2) Martin's Axiom (MA) implies se = 2! .

(3) There is a model of ordinary set theory (ZFC) in whih se <

2! .

In 1994, Andreas Blass observed that Eda's proofs establish

onnetions between the Speker-Eda number and some of the ardinal invariants of the real numbers whih were dened at the

beginning of this setion.

Theorem 2.5 (Eda [15℄, Blass [8℄) (1) p se d.

(2) add(L) se b.

Conjeture 2.6 (Blass [8℄) se = add(B).

3. P and innitary logi

From the logial point of view, a group G is a struture G =

(G; +G ; G ; 0G ) whih satises the axioms for a group. In this

setion we use L to denote the voabulary of groups, that is, L

ontains the onstant, unary, and binary funtion symbols 0, ,

and + to name the zero, inverse, and addition of a group. There

are other possible hoies for the voabulary of groups, but for the

The Baer-Speker Group

17

sake of deniteness we shall x L as above. It is also a fat that

all the theorems of logi presented here are true in muh greater

generality.

The innitary language L1 is the smallest lass of formulas

in the voabulary L whih is losed under negations, onjuntions

of arbitrary length, and strings of quantiers

(9x1 9x2 : : : 9x : : :)(<)

of length less than . This innitary language is more expressive than the rst-order language of groups where one is limited

to negations, nite onjuntions, and nite strings of quantiers.

While the axioms for a group are rst-order, many of the interesting group-theoreti properties annot be expressed by rst-order

sentenes. For example, the following sentene of L1! says that

a group is torsion:

(8g)(g = 0 or 2g = 0 or 3g = 0 or : : : or ng = 0 : : :):

But the onept of torsion annot be axiomatized in a rst-order

language. Innitary logi an express the onepts of {freeness,

{purity, < {generatedness and so on. The paper by Barwise [3℄

is an exellent introdution to the bak and forth methods harateristi of innitary logi. Other useful referenes for innitary logis are the book by Barwise [4℄ and the artile by Dikmann [12℄. A typial problem in general innitary model theory

involves determining whether there are innitarily equivalent nonisomorphi models in various ardinalities, [40℄.

Denition Two groups A and B are L1 {equivalent if and only

if for every sentene ' in L1 : ' is true in A i ' is true in B .

So L1 {equivalent groups annot be distinguished by a sentene in the innitary language L1 . There is an algebrai haraterization of innitary equivalene whih is very useful and perhaps more familiar.

Theorem 3.1 (Karp [27℄, Benda [6℄, Calais [9℄) Two groups A

and B are L1 {equivalent if and only if there is a {extendible

system of partial isomorphisms from A to B .

18

IMS Bulletin 40, 1998

A {extendible system of partial isomorphisms from A to B is

a family F of isomorphisms between subgroups of A and B whih

has the {bak-and-forth property: if 2 F is an isomorphism

from M1 A onto N1 B and X (respetively Y ) is a subset

of A (respetively B ) of ardinality less than , then there exists

2 F from M2 onto N2 suh that M1 M2 A, N1 N2 B ,

extends and X (Y ) is a subset of M2 (N2 ).

Using this algebrai onept, it is easy to hek for example

that any two unountable free groups are L1! {equivalent. {

extendible systems are a natural generalization of Cantor's tehnique for showing that there is (up to isomorphism) exatly

one unbounded dense ountable linear order, namely the linearly

ordered set of the rational numbers [3℄. Indeed, for ountable

groups, innitary equivalene and isomorphism are synonymous:

Theorem 3.2 (Sott [39℄) If A and B are ountable L1! {

equivalent groups, then A and B are isomorphi.

The innitary model theory of abelian groups was intensively

studied in the 1970's by Barwise, Eklof, Fisher, Gregory, Kueker,

and Mekler (see [5, 16, 17, 23, 28℄ for example). One of the rst

important results is due to Eklof, who sueeded in determining

whih groups are innitarily equivalent to free groups.

Denition A subgroup A of G is {pure if for every subgroup B

suh that A B G and B=A is < {generated (i.e. generated

by fewer than elements), A is a diret summand of B .

Theorem 3.3 (Eklof [16℄) A group G is L1 {equivalent to a

free group if and only if every < {generated subgroup of G is

ontained in a free, {pure subgroup of G.

For the purposes of this exposition, it is suÆient to know the

following orollaries.

Corollary 3.4 A group G is L1! {equivalent to a free group i

every subgroup of G of nite rank is free.

Eklof used this result to dedue a very famous riterion for

freeness in ountable groups:

Corollary 3.5 (Pontryagin's Criterion [35℄) A ountable group is

free i every subgroup of nite rank is free.

The Baer-Speker Group

Apply Sott's Theorem 3.2 to Corollary 3.4.

Corollary 3.6 (Kueker) A group is L1! {equivalent

19

Proof:

group i it is !1 {free.

to a free

Now we an return to the Baer-Speker group P and see what

these fats tell us.

Corollary 3.7 (Keisler-Kueker) The Baer-Speker group P is

L1! {equivalent to a free group. The lass of free groups is not

denable in L1! .

Corollary 3.8 (Eklof [16℄) The group P is not L1!1 {equivalent

to a free group.

Sine free groups are slender, it follows too from Corollary

3.7 that the lass of slender groups is not denable in L1! . It

might be tempting to onjeture that P is not L1!1 {equivalent

to a slender group. Another possible suggestion is that P is not

L1se {equivalent to a slender group. Mekler showed that if is a

strongly ompat ardinal, then the lass of free groups is denable

in L1 . This prompts the question whether the lass of slender

groups is denable in L1 if is strongly ompat. Eklof and

Mekler have developed appliations of other generalized logis to

problems of abelian group theory in the papers [18℄ and [19℄.

4. The lattie of subgroups of P

The broad thrust in this setion is to desribe some reent researh

on the omplexity of the lattie of subgroups of P. One way to

measure this omplexity is to study what sorts of groups an be

embedded into P. Very generally, the natural questions often have

the form whether there are families of maximal possible size of

subgroups of P whih are strongly dierent (non-isomorphi) in

some preisely dened sense.

An example of this type of theorem in the ontext of general

abelian groups is the following.

Theorem 4.1 (Eklof, Mekler and Shelah [21℄) Under various set-

theoreti hypotheses, there exist families of maximal possible size

of almost free abelian groups whih are pairwise almost disjoint

(the intersetion of any pair ontains no non-free subgroup).

20

IMS Bulletin 40, 1998

There is an inverse orrelation between the size of the family

and the strong dierene of its members. If one onsiders families

of pure subgroups of P and takes the notion of strong dierene to

mean that the only homomorphisms between any pair are those of

nite rank, then it is possible to prove the existene of a strongly

dierent family of maximal size.

Theorem 4.2 (Corner and Goldsmith [10℄) Let D be the subgroup

of P ontaining S suh that D=S is the divisible part of P=S.

Let = 2! . There exists a family C onsisting of 2 pure subgroups G of D with D=G rank{1 divisible where eah G is slender,

essentially-indeomposable, essentially-rigid with End(G) = Z +

E0 (G), where E0 (G) is the ideal of all endomorphisms of G whose

images have nite rank.

A similar type of question is the following: does there exist a

family of 2!1 non-isomorphi pure subgroups of P, eah of ardinality !1 , suh that the intersetion of any pair is free? The answer

is positive.

Theorem 4.3 (Shelah and Kolman [41℄) There exists a family

fG : < 2!1 g of pure subgroups of P suh that

(1) eah G has ardinality !1 ;

(2) if 6= , then G \ G is free.

The question whether ertain lasses of group an be embedded in P sometimes leads to independene results. Reall that a

group G is !1 {separable if every ountable subset of G is ontained

in a free diret summand of G.

Theorem 4.4 (Dugas and Irwin [14℄) Embeddability of !1 {

separable groups of ardinality !1 in P is independent of ZFC.

Reexive subgroups of P have also been studied in some

depth. The following result was known for many years under the

additional assumption of the Continuum Hypothesis.

Theorem 4.5 (Ohta [34℄) There exists a non-reexive dual subgroup of P.

The variety displayed in this seletion of results on the BaerSpeker group P illustrates how this easily denable abelian group

is a soure of interesting researh problems whose solutions often

The Baer-Speker Group

21

reveal unexpeted onnetions with problems in other domains of

mathematis.

Referenes

[1℄ R. Baer, Abelian groups without elements of nite order, Duke Math. J.

3 (1937), 68-122.

[2℄ T. Bartoszynski, Additivity of measure implies additivity of ategory,

Trans. Amer. Math. So. 281 (1984), 209-213.

[3℄ J. Barwise, Bak and forth through innitary logi, pp.5-33 in : M.

Morley (ed.), Studies in Model Theory, 1975.

[4℄ J. Barwise, Admissible Sets and Strutures. Springer-Verlag: Berlin,

1975.

[5℄ J. Barwise and P. C. Eklof, Innitary properties of abelian torsion

groups, Ann. Math. Logi 2 (1970), 25-68.

[6℄ M. Benda, Redued produts and non-standard logis, J. Sym. Logi

34 (1969), 424-436.

[7℄ S. Ben-David, On Shelah's ompatness of ardinals, Israel J. Math. 31

(1978), 34-56.

[8℄ A. Blass, Cardinal harateristis and the produt of ountably many

innite yli groups, J. Algebra 169 (1994), 512-540.

[9℄ J. P. Calais, La methode de Frasse dans les langages innis, C. R.

Aad. Si. Paris 268 (1969), 785-788.

[10℄ A. L. S. Corner and B. Goldsmith, On endomorphisms and automorphisms of some pure subgroups of the Baer-Speker group, pp.69-78 in :

R. Goebel et al. (eds.), Abelian group theory and related topis, Contemp. Math. 171 (1994).

[11℄ K. J. Devlin, Construtibility. Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 1984.

[12℄ M. Dikmann, Larger innitary languages, Chapter IX in : J. Barwise

and S. Feferman (eds.), Model-theoreti Logis. Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 1985.

[13℄ E. van Douwen, The integers and topology, pp.111-167 in : K. Kunen

and J. E. Vaughan (eds.), Handbook of Set-theoreti Topology. NorthHolland: Amsterdam, 1984.

[14℄ M. Dugas and J. Irwin, On pure subgroups of artesian produts of

integers, Results in Math. 15 (1989), 35-52.

22

IMS Bulletin 40, 1998

[15℄ K. Eda, A note on subgroups of ZN , pp.371-374 in : R.Goebel et al.

(eds.), Abelian Group Theory. Leture Notes in Mathematis 1006.

Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 1983.

[16℄ P. C. Eklof, Innitary equivalene of abelian groups, Fund. Math. 81

(1974), 305-314.

[17℄ P. C. Eklof and E. R. Fisher, The elementary theory of abelian groups,

Ann. Math. Logi 4 (1972), 115-171.

[18℄ P. C. Eklof and A. H. Mekler, Innitary stationary logi and abelian

groups, Fund. Math. 112 (1981), 1-15.

[19℄ P. C. Eklof and A. H. Mekler, Categoriity results for L1 {free algebras, Ann. Pure and Appl. Logi 37 (1988), 81-99.

[20℄ P. C. Eklof and A. H. Mekler, Almost Free Modules. North-Holland:

Amsterdam, 1990.

[21℄ P. C. Eklof, A. H. Mekler and S. Shelah, Almost disjoint abelian groups,

Israel J. Math. 49 (1984), 34-54.

[22℄ L. Fuhs, Innite Abelian Groups, Vol. I. Aademi Press: New York,

1970.

[23℄ J. Gregory, Abelian groups innitarily equivalent to free groups, Noties

Amer. Math. So 20 (1973), A-500.

[24℄ G. Heinlein, Vollreexive Ringe und shlanke Moduln, dotoral dissertation, Univ. Erlangen, 1971.

[25℄ W. Hodges, In singular ardinality, loally free algebras are free,

Algebra Universalis 12 (1981), 205-259.

[26℄ T. Jeh, Set Theory. Aademi Press: New York, 1978.

[27℄ C. Karp, Finite quantier equivalene, pp.407-412 in : J. Addison et al.

(eds.), The Theory of Models. North-Holland: Amsterdam, 1965.

[28℄ D. W. Kueker, L1!1 {elementarily equivalent models of power !1 , pp.

120-131 in : Logi Year 1979-80, Leture Notes in Mathematis 859.

Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 1981.

[29℄ K. Kunen, Set Theory. North-Holland: Amsterdam, 1980.

[30℄ M. Magidor and S. Shelah, When does almost free imply free?, J. Amer.

Math. So. 7 (1994), 769-830.

[31℄ D. A. Martin and R. M. Solovay, Internal Cohen extensions, Ann. Math.

Logi 2 (1970), 143-178.

[32℄ A. W. Miller, Additivity of measure implies dominating reals, Pro.

Amer. Math. So. 91 (1984), 111-117.

The Baer-Speker Group

23

[33℄ R. Nunke, Slender groups, Ata Si. Math. (Szeged) 23 (1962), 67-73.

[34℄ H. Ohta, Chains of strongly non-reexive dual groups of integer-valued

ontinuous funtions, Pro. Amer. Math. So. 124 (1996), 961-967.

[35℄ L. S. Pontryagin, The theory of topologial ommutative groups, Ann.

Math. 35 (1934), 361-388.

[36℄ J. Raisonnier and J. Stern, The strength of measurability hypotheses,

Israel J. Math. 50 (1985), 337-349.

[37℄ F. Rothberger, Eine Aequivalenz zwishen der Kontinuumhypothese

und der Existenz der Lusinshen und Sierpinskishen Mengen, Fund.

Math. 30 (1938), 215-217.

[38℄ S. A. Saxon and L. M. Sanhez-Ruiz, Barrelled ountable enlargements

and the bounding ardinal, J. London Math. So. 53 (1996), 158-166.

[39℄ D. Sott, Logi with denumerably long formulas and nite strings of

quantiers, pp.329-341 in : J. Addison et al. (eds.), The Theory of

Models. North-Holland: Amsterdam, 1965.

[40℄ S. Shelah, Existene of many L1 {equivalent, non-isomorphi models

of T of power , Ann. Pure and Appl. Logi 34 (1987), 291-310.

[41℄ S. Shelah and O. Kolman, Almost disjoint pure subgroups of the BaerSpeker group, submitted.

[42℄ E. Speker, Additive Gruppen von Folgen ganzer Zahlen, Portugaliae

Math. 9 (1950), 131-140.

[43℄ O. Spinas, Cardinal invariants and quadrati forms, pp.563-581 in :

H. Judah (ed.), Set Theory of the Reals. Israel Mathematial Conferene Proeedings (Gelbart Researh Institute, Bar-Ilan University),

1993.

[44℄ J. E. Vaughan, Small unountable ardinals and topology, pp.195-218

in : J. van Mill and G. M. Reed (eds.), Open Problems in Topology.

North-Holland: Amsterdam, 1990.

Eoin Coleman,

King's College London,

Strand,

London WC2R 2LS,

England

email: okolmanmember.ams.org