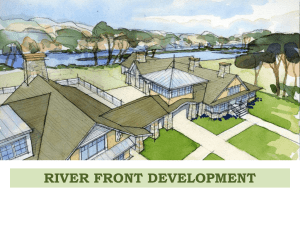

1 RECLAIMING THE RIVERFRONT AS CATALYST FOR NEIGHBORHOOD

advertisement