Document 11002330

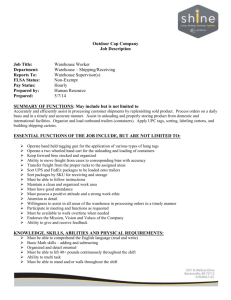

advertisement