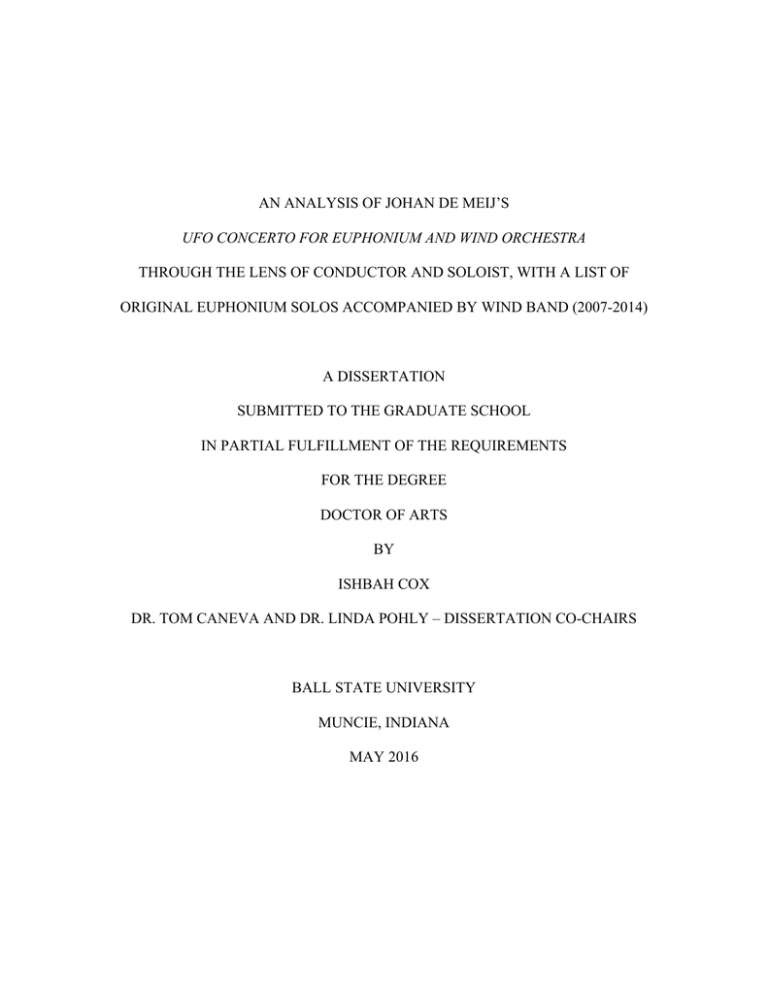

AN ANALYSIS OF JOHAN DE MEIJ’S

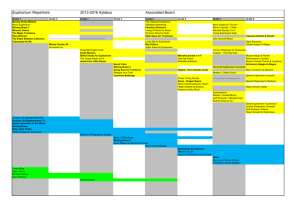

advertisement