Document 11002199

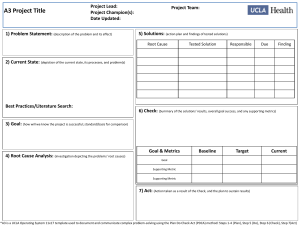

advertisement