On Parfit’s Repugnant Conclusion Department of Philosophy, Rutgers University Joy Li

advertisement

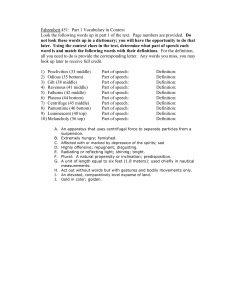

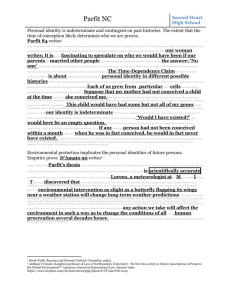

Volume 1 (2013) On Parfit’s Repugnant Conclusion Joy Li Department of Philosophy, Rutgers University Abstract There are many factors that determine goodness of a world, but given the limited resources available, perhaps the most telling indicators are population size and quality of life. In his famous book Reasons and Persons, Derek Parfit presented a puzzle in order to illustrate that seemingly reasonable assumptions about tradeoffs between quality and quantity lead to what he calls the “Repugnant Conclusion.” According to the Repugnant Conclusion, a world in which there are a large number of people leading lives barely worth living is better than a world in which there are fewer people leading excellent lives. Many philosophers have tried to solve this puzzle, but without clear success. In this paper, I will explain Parfit’s Continuum Argument for the Repugnant Conclusion along with a new answer to the problem posed by the Repugnant Conclusion as found in his unpublished manuscript. I end by raising some objections to his solution. I. Introduction Let’s begin with a simplifying assumption: suppose that there are only two factors relevant to determining how good a world is – the size of the population, and the quality of lives they lead. All other factors relevant to such an assessment are the same in every world we compare, insofar as they are consistent with changes in population size and quality of life. This is an attractive simplification, since these two factors are arguably the most important variables in determining the overall goodness of a world. But because resources are finite in any world, we are forced to balance these values.1 However, tradeoffs between the goodness that arises from having a certain number of lives and the goodness that arises from having lives of high quality are not a straightforward matter. In his Continuum Argument for the Repugnant Conclusion, Derek Parfit showed how seemingly innocuous principles governing such tradeoffs lead to what he called “The Repugnant Conclusion,” the intuitively implausible claim that a world with a vast number of people leading lives barely worth living I owe a very large debt of gratitude to Dr. Ruth Chang (Rutgers University) for reading many, many drafts of both this paper an earlier related work. Thanks also to Aleksi Anttila for helpful criticism on the last draft. A version of this paper was presented in 2013 at the Third Mid-Hudson Valley Undergraduate Philosophy Conference at Marist College. 1 Although it’s possible for scientific breakthroughs and technological advancements to improve efficiency of resource allocation, at any one moment in time, we are still forced to weigh the two. 1 Joy Li/Volume 1 (2013) is better than a world with a large number of people leading extremely good lives. In other words, the Repugnant Conclusion holds that a world in which a very large number of people leading lives with Mozart and caviar is worse than a world with an almost infinitely larger number of people scraping by on muzak and potatoes. Since Parfit’s introduction of the paradox, philosophers have attempted to resolve the problem posed by the Repugnant Conclusion without much success.2 In the past year, Parfit has developed a new solution to the puzzle which I will summarize and discuss in this paper. This paper has four parts. I will introduce the Continuum Argument for the Repugnant Conclusion in Part II, discuss the “Simple View” upon which the continuum Argument relies in Part III, explain Parfit’s new solution posed by the Repugnant Conclusion in part IV, and present possible objections to Parfit’s view in part V. II. The Continuum Argument for the Repugnant Conclusion Let world A be a reasonably good world – that is, one with a population of ten million or so, all with very good lives. Most people believe that: Fig. 1: Continuum of Worlds 2 See Arrhenius, Gustaf, Ryberg, Jesper and Tännsjö, Torbjörn, "The Repugnant Conclusion", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2010 Edition), ed. Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL= <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2010/entries/repugnant-conclusion/>. 2 Joy Li/Volume 1 (2013) (1) Given any world (for example, A), there is a better world (for example, B), which contains a bigger population with lives only a little worse than those in the original world. The second world is better because there is a sufficient number of additional people with a sufficient quality of life whose existence contributes more to the overall goodness of the world than the small decrease in the quality of life of the original population. We can repeat the same procedure with B to get C, C to get D, etc., until we get a continuum of worlds from A to Z. (2) If A is worse than B and B is worse than C, then A is worse than C. This is the transitivity principle, which applies to better than, equal to, and worse than. Unfortunately, (1) and (2) lead to: (3) The Repugnant Conclusion: All else being equal, there is some world Z with an immense population living lives barely worth living which must be better than A. It is important to note that when we use the comparative relations of better than, equal to, and worse than, we are not implying that there is an underlying scale of measurement for the items we are comparing. There is no absolute scale of goodness – such abstract comparisons should not be understood in the mathematical sense as implying commensurability (having a common unit or scale of measurement) on top of comparability (having certain specific characteristics or values in common). For instance, it makes sense to compare the suitability of water and juice as drinks to quench your thirst since they are both common drinks even though there is no absolute scale of ‘goodness as a drink’ one can use to measure water and juice against. Similarly, just as the phrase “becoming a better person” does not imply a scale of goodness for persons, so the phrase “is a better world” does not imply a scale of goodness for worlds. When two things are comparable but incommensurable, they are imprecisely comparable.3 The conclusion presented in (3) is very counter-intuitive since Z is neither objectively nor subjectively appealing, especially compared to A.4 Our intuition seems to be at odds with itself – the reasonable belief presented in (1) combined with the seemingly incontrovertible transitivity of “worse 3 I take precise comparability to be Boolean – a comparison is either precisely comparable (in which case the difference is commensurable, or quantifiable, as in the donut is more expensive than the bagel by $1) or not (in which case there are degrees of imprecision involved). 4 It may seem strange to some that the Repugnant Conclusion is objectively unappealing. Perhaps the motivation comes from the idea that if one were to choose one world to bring about, where it need not be the case that he or she exists in that world, the person would pick Z, because one would be most likely to exist in that world. But that is not objective enough. One ought to choose between worlds behind a Rawlsian Veil of Ignorance, where the betterness of worlds is not evaluated solely on the basis of individual preference, but from a more universal perspective. 3 Joy Li/Volume 1 (2013) than” in (2) lead us to the “intrinsically repugnant” (3).5 There has been much debate over what the proper response to this argument ought to be. However, neither (1) nor (2) have been rejected on reasonable grounds. Thus, we must figure out some additional premises that will provide the needed justification for avoiding the Repugnant Conclusion. III. The Simple View & Parfit’s Response I will present what Parfit calls ‘the Simple View’ before explaining Parfit’s Imprecisionist Lexical View, since the Continuum Argument for the Repugnant Conclusion presupposes it, and Parfit’s new response appeals it by drawing attention to its limits. According to the Simple View (V1): Someone’s existence is in itself good, and makes the world in one way better, if this person’s life is good to live, or worth living. Someone’s existence is in itself bad, and makes the world worse, if this person’s life is bad to live, or worse than nothing. If someone’s life is neither good nor bad to live, so that this person’s level of well-being is zero, this person’s existence has no intrinsic value, making the world neither better nor worse. In other words, a world with more people is better in at least one way if these additional people are leading lives worth living because these lives are intrinsically good. Since this view ties the existence of lives worth living to intrinsic goodness, there is no number of lives beyond which the addition of more lives would be either neutral or bad. That is, on the Simple View, the intrinsic worth of a good life is entirely independent of a world’s population size. Any attempted solution to the problem posed by the Repugnant Conclusion should either adhere to the Simple View or provide an alternative account of how the value that arises from a single good life contributes to the value of a world. But alternative accounts would have to reject at least one of the following: (a) a life worth living is inherently good (b) lives worth living are non-diminishingly good (c) all else being equal, adding an additional life worth living makes the world in one way better 5 Derek Parfit, Reasons and Persons (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 387-390. 4 Joy Li/Volume 1 (2013) Yet all three are intuitively appealing claims that most would accept outside of this context, and so to reject one or more of them would seem like an ad hoc solution, one created for the purpose of resolving the Repugnant Conclusion but which is not otherwise tenable. Indeed, as we will see later, Parfit includes the Simple View as one of his premises, and claims that the Simple View implies the Repugnant Conclusion. But the implication can’t be a logical one, because while the Simple View is necessary for (1) to be true, it isn’t sufficient to lead to the Repugnant Conclusion. The Simple View only claims that the addition of good lives has an intrinsic worth independent of population size; in the continuum of worlds, we are trading some decrease in quality of life for these additional persons. The former is a statement about absolute value while the latter concerns comparative value. Rather, the Repugnant Conclusion results from the combination of the Simple View combined with the beliefs that (1) all things considered, it is intrinsically better to have a much greater population in exchange for a slight decrease in quality of life, and (2) the transitivity of worse than holds for pair-wise comparisons of worlds. IV. Parfit’s Imprecisionist Lexical View In an unpublished manuscript, Parfit advocates a new solution to the problem posed by the Repugnant Conclusion, what he calls ‘the Imprecisionist Lexical View’ or ‘V.’ This view makes the following assumptions:6 (V1) The Simple View: “Anyone’s existence is in itself good if this person’s life is worth living, or a life that is good to live. Such goodness has nondiminishing value, so if the number of such people grew, the combined goodness of their existence would have no upper limit. (V2) If there existed many people who would all have some high quality of life, that would be better than if there existed any number of people whose lives, though worth living, would be, in certain ways, much less good to live. (V3) When two possible worlds would contain different numbers of people, this fact makes these worlds less precisely comparable. 6 Derek Parfit, Reasons and Persons, 413-14. Note that V1 is the Simple View, and V2 is the negation of (1), the first premise of the argument for the Repugnant Conclusion. 5 Joy Li/Volume 1 (2013) There are many terms that Parfit employs which must be explained in order to clarify his view, so I will explain them as they occur in his argument. First, one must be careful about Parfit’s usage of the word “better.” As V3 makes clear, Parfit believes that any two worlds on the continuum can only be imprecisely compared, because they are qualitatively different in virtue of having different numbers of people, which Parfit calls “different-number-based imprecision”. Unlike cases of commensurable (or precise) comparability, cases of imprecise comparability can vary in two possible ways. There are degrees of imprecision determined by how qualitatively different the two items being compared are. This is called the “margin of imprecision.” The larger the margin, the harder it gets, in some sense, for two things to go from being imprecisely equal to having an improved one be imprecisely better than the other. Every imprecise comparison involves a margin of imprecision. In the water versus juice example, if the juice were inordinately expensive, then the evaluation might tip in favor of water because the margin formed by the qualitative difference between water and juice has been overcome. No matter how healthy or delicious the juice might have been, the agent would not think the price was justified. In the pair-wise comparison of worlds, the more two worlds differ in population size, the larger the margin and the more imprecisely comparable they become. There are also cases of imprecisely equal comparisons: when two things are imprecisely equal, it is possible for one to be pareto better than the other – that is, better or just as good as the other in every single way – and still not be better all things considered because of the margin of imprecision. This makes imprecise equality cases distinct from precise equality cases. For example, consider the attractiveness of two careers, say writer versus doctor. If neither is better than the other, and we improve the writing career’s salary by $1, this would not tip the scale in favor of the person becoming a writer. So, the two careers are considered imprecisely equal. In order for one of the careers to become imprecisely better, it must be improved in some significant way. Moreover, the improvement can’t be merely with respect to a single factor in the overall evaluation. In our example, the extra dollar doesn’t tip the scale in favor of the writing career. According to Parfit, on the continuum of worlds, a world can overcome its margin of imprecision if it includes more lives that are not only worth living (above the Zero Level) but also above the High Level. For simplicity, let us pretend that these are quantifiable and set the High Level to 75, and let M be some moderate population size, like 10 million. As figure 2 (below) shows, F (5M, 80) is imprecisely better than A (M, 100), but S (1000M, 60) is imprecisely worse than F (5M, 80) and imprecisely worse than A (M, 100). In the same manner, Z (M^M, 1) is imprecisely worse than A (M, 100). Parfit justifies 6 Joy Li/Volume 1 (2013) these comparisons by claiming the “lexical superiority” of the lives above High Level over those below it. X is lexically superior to Y when there exists an amount of X such that it is better than any possible amount of Y. In other words, Parfit blocks the Repugnant Conclusion by claiming that there is a certain population size of individuals leading very good lives A-type lives such that it is overall better than any possible number of people leading lives barely worth living Z-type lives, though those lower quality lives are also intrinsically and non-diminishingly good. V. Objections There are several problems for this view. Notice that for any given pair of worlds, W2 is only imprecisely better than W1 if W2 has more people, and the extra people in W1 are living above the High Level. If this High Level cutoff is a precise one, we are forced to conclude that W1 and W2 are imprecisely equal even if those extra people in W2 are only a little below this cutoff. If this cutoff is not a precise one, it is hard to see where imprecisely equal ends and imprecisely better than sets in. The notion of lexical superiority is subject to a similar concern. For A-type lives to be lexically superior to Z-type lives, A needs to have a certain large number of people, all living above the High Level, while everyone in Z lives well below the High Level. But Parfit does not explain how a certain population size in the A-type world can trigger lexical superiority over Z-type lives. After all the margin of imprecision varies over the difference in population sizes between the two worlds, which depends on Z’s population since it is the only variable. For instance, let 75 be the High Level, and let M be the cutoff number of lives required for A-type lives to be lexically superior to Z-type lives. Then A (M, 100) is better than Z(N, 1) where N can be any population size. But A- (M, 70) is not lexically superior to Z(P, 1) 7 Joy Li/Volume 1 (2013) where P can be any population size. That the very strong notion of lexical superiority sets in so quickly along a continuum is very counterintuitive. Another problem arises when we change the characteristics of A-type worlds and Z-type worlds. According to Parfit’s view, A-type worlds need to contain a certain number of people in order to be better than any Z-type world, regardless of the number of people in Z. If we take a Z-type world that has the same number of people as A, certainly it should be true that A is (precisely) better than Z. If A has one more person than Z, then by lexical superiority, A should still be better than Z, though imprecisely so. Yet because there is different number based imprecision, there is a margin of imprecision which arises when we compare the two worlds, such that it is only overcome by the fact that people in Z are living below the High Level, whereas those in A are above it. But that seems like an artificial construct – we say in the case of A and Z having the same population that A is obviously better because the people have better lives, not because A-type lives are qualitatively different enough from Z-type lives. The underlying reasons for why one world is better than another should remain constant when we make these types of comparisons, in order for us to say a particular world among the continuum is the optimal one, which we should attempt to bring about. VI. Conclusion For decades, many philosophers have attempted and failed to explain how one should avoid the conflicting intuitions that result in the Repugnant Conclusion. A recent proposal by Derek Parfit in his manuscript “Towards Theory X: Part Two” involves a complex, two-part answer involving imprecise comparability and lexical superiority. Worlds containing different populations can only be imprecisely compared. So A-type worlds are imprecisely better than Z-type worlds not only because they contain different populations sizes, but also because A-type lives are lexically superior to Z-type lives. But this Imprecisionist Lexical View has unappealing consequences. The cutoff posed by High Level implies a discontinuity as does lexical superiority. More significantly, when A and Z contain the same population size, A is better than Z for a different reason than when they contain different population sizes. If my analysis is correct, then the Repugnant Conclusion is still unresolved because there are no plausible answers. 8