DOWNTOWN CHATTANOOGA: PLANNING AND PRESERVATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL

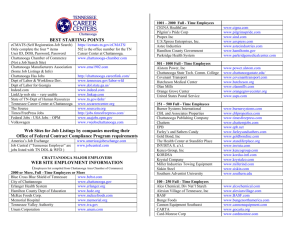

advertisement