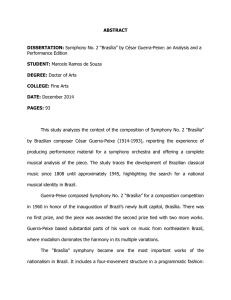

SYMPHONY NO. 2 “BRASÍLIA” BY CÉSAR GUERRA-PEIXE: A DISSERTATION

advertisement