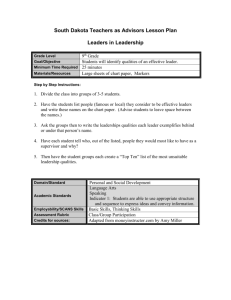

Non-Standard Features

advertisement