Document 10975333

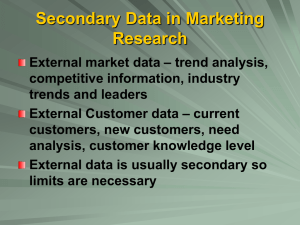

advertisement