Document 10974243

advertisement

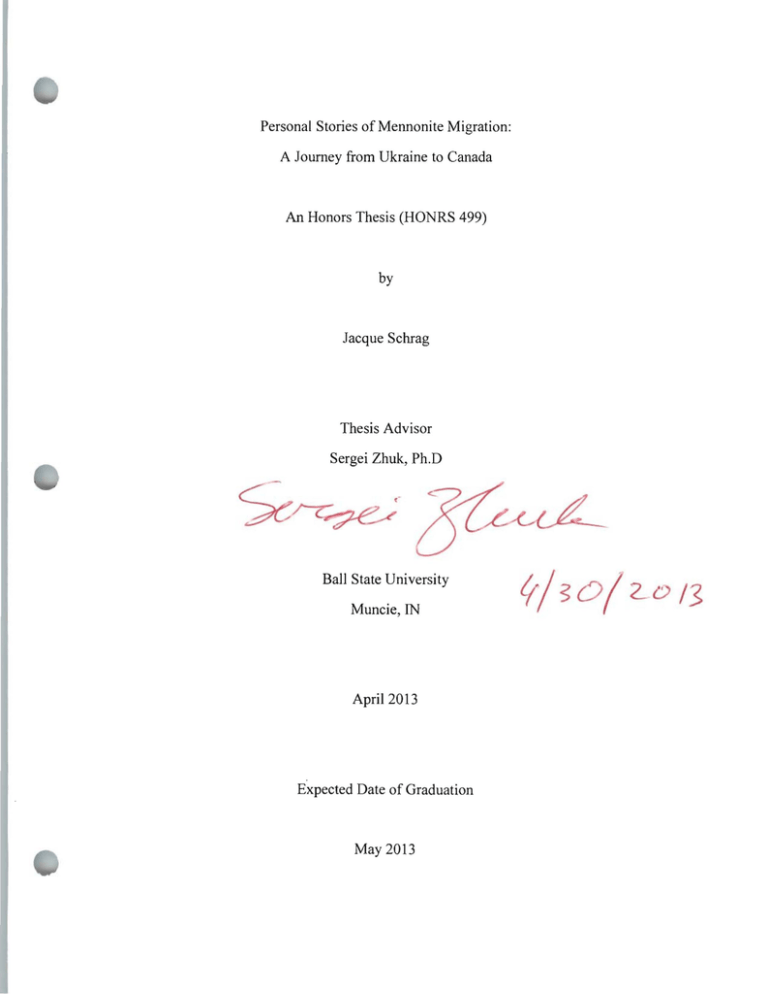

Personal Stories of Mennonite Migration: A Journey from Ukraine to Canada An Honors Thesis (HONRS 499)

by

Jacque Schrag Thesis Advisor Sergei Zhuk, Ph.D Ball State University Muncie, IN April 2013 Expected Date of Graduation May 2013

Schrag 1

Abstract

Without a doubt, the Bolshevik Revolution altered the course of world history. Millions

of lives were affected by the policies enacted by the conununist leadership. German-speaking

Mennonites living in Ukraine were one group that was particularly affected by Bolshevik

policies, and more than 22,000 Mennonites would emigrate during the 1920s from the Soviet

Union to Canada and other Western countries to escape persecution. Among those who fled the

rapidly deteriorating conditions in the Ukrainian countryside were my paternal grandmother's

parents, Henry Koop and Margaret Enns. This thesis will discuss this major wave of Mennonite

inunigration, focusing on how Mennonites were targeted for persecution because of their

German heritage and their relative wealth. Using the stories and accounts of my great

grandparents and their families' struggle to escape, I hope to place my family in larger historical

context and illustrate through their experience the danger and uncertainty faced by Mennonites

trying to escape the Soviet Union during the 1920s.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Sergei Zhuk for advising me on this project. He provided

invaluable advice and numerous books and articles, without which I would not have been able to

complete this project.

I would also like to thank my family, especially the Koops, for answering my questions

about Oma and Opa, allowing me to borrow family artifacts, and supporting me throughout the

process of this proj ect.

Schrag 2 Table of Contents

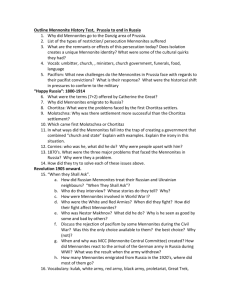

Personal Stories of Mennonite Migration: A Journey from Ukraine to Canada ............................. 3 Historiography of UkrainianlRussian Mennonite Migration ...................................................... 6 Cultural Discrimination ...................... ........ .. ..................... .......................... .................. ..... ......... 9 Economic Conditions ................................................................................................................ 13 The Anarchy of Civil War ..... ... ......... ............................. ............................ ...................... ......... 18 Conclusion..................... ....... ......................................... .. ..................... ..................................... 22 Appendix A: Family Trees ........... ................................................................................................. 25 Appendix B: Interview Questions and Transcription ......................................... ............... ........... 28 Appendix C: A Pilgrimage - The Story of Katharine Janzen and Cornelius Enns ......... ... .......... 43 Appendix D: Passenger List. ......................................................................................................... 51 Personal Artifacts .......................................................................................................................... 53 Bibliography ................................................................................................................................. 53 Schrag 3

Personal Stories of Mennonite Migration:

A Journey from Ukraine to Canada

\\!hy should we concern ourselves with the stories of immigrants of the past? \\!hat

relevance do those stories have in today's society? In nations of the Western Hemisphere, the

journeys of immigrants have always played an important role. Without the mass migration of

people over time from Europe, Asia, and Africa, the West would be completely different. The

stories of many of these immigrants naturally become lost overtime, but that does not negate

their importance or their influence. All individuals come from somewhere, and investigation into

the histories of individual families or small groups can lead to greater discoveries about the time

in which those ancestors lived. The circumstances under which immigrants decided to leave their

native homelands have residual effects and could easily have impacted their decisions and

actions in their new homes.

The circumstances in which two of my great grandparents, Henry and Margaret Koop,

emigrated with their families from Ukraine to Canada in the 1920s were not quickly forgotten

and would have consequences that I feel even now, three generations later. They were among

nearly 22,000 Russian Mennonites who fled Russia after 1917.) Henry Koop came from a

wealthy family that lived in the Molotshna settlement and would emigrate to Canada in 1924. In

Canada, he would meet Margaret Enns, my great-grandmother, who came from a poor family

from Schroenfeld, Ukraine in 1926. Despite being forced to flee their homelands with their

families because of their Mennonite beliefs, Henry and Margaret were practicing Mennonites

until their deaths in 2000 and 2001, respectively. Even though the Mennonite tradition was the

1 (Loewen,

et al. 1996, 251)

Schrag 4

circumstance that forced them to leave Ukraine or face continued persecution, they did not

abandon their faith when they arrived in Canada, despite the uncertainty that they and many

other families faced as "the golden age" of Mennonites came to an end in 1917?

The golden age for Mennonites had its beginnings in the 1780s, when Empress Catherine

the Great of Russia "invited Europeans to settle in Russia" in exchange for "165 acres of farm

land, religious freedom, and freedom from military service 'forever",.3 The Mennonites are a

religious group of people that follow the teachings of Jesus Christ, believe in Anabaptism or

adult baptism, and practice non-violence. Derived from Anabaptist groups that emerged during

the Protestant Reformation, Mennonites are named for their leader, Menno Simons. Simons was

a Dutch preacher who converted from Catholicism to Anabaptist beliefs in 1536, but unlike other

Anabaptist groups, believed in pacifism. 4 Persecuted by European rulers for their religious

beliefs, Mennonites began to spread out from Switzerland to other parts of Europe, settling in

areas where state leaders were more tolerant of their religious beliefs, particularly their need for

military exemption. Many Mennonites would eventually settle in Prussia, cementing their ties

with the German language and culture.

After persecution in Western Europe, Catherine's promise of allowing Mennonites to

have both land and practice their religion without state interference was seen by many as a "gift

from God".5 Their hard working nature had benefited them economically in Europe and was

what had prompted Catherine's invitation for them to migrate 6 , and for many who migrated to

Russia to settle present-day Ukraine, they continued to prosper. Living in their own settlements,

(Marrow 1983) (Loewen, et al . 1996, 213) 4 (Loewen, et al. 1996, 111) 5 (Marrow 1983) 6 (Zhuk 2004, 40-41) 2

3

Schrag 5

like Choritza and Molotshna, continued to maintain their German language and culture. Focused

on their work, Mennonite families that prospered were able to create large farms and even

factories that produced technologically advanced farm equipment. With their increased wealth,

they were able to hire their Russian neighbors as workers, fannhands, and house workers.

The Mennonite experience in Russia also brought about ideological religious changes,

which would eventually lead to a split between the Mennonites and lead to the formation of the

Mennonite Brethren Church. As groups of Mennonites came under the influence of Pietistic

settlers from Europe, they distanced themselves from the "conservers" or the traditionalist

Mennonites. This division within the Mennonite community called into question the Mennonite

identity and led to a religious awakening, forcing all Mennonites to examine their beliefs. 7

The first wave of Mennonite emigration from Russia and another split within the

community was prompted by events that occurred in 1871, when the government of Tsar

Alexander II announced that the Mennonite colonists would lose their right to military

exemption. Despite being given the option to participate in non-combatant roles such as in

forestry or the health corps, nearly 18,000 Mennonites left Russia for the United States and

Canada during the 1870s and 1880s, unwilling to compromise their faith and commitment to

pacifism. 8 The Koop and Enns families were among the families who made the decision to stay,

despite their men being conscripted to participate in the military. Cornelius Enns, Margaret's

father, was one such individual- he was conscripted to work as a secretary for the Army during

World War 1. 9

For detailed information on the Mennonite revival and its impact on other groups, see (Zhuk 2004, 153-163) (Loewen, et al. 1996, 240) 9 (Adelaide Fransen 2013) 7

8

Schrag 6

The end of peace for the Mennonites, however, came after the Bolshevik Revolution in

1917. As all of Russia was plunged into a Civil War between the Reds, the Whites, and anarchist

groups, Mennonites in particular found themselves as targets in the chaos. Their use of the

German language and their distinctiveness from other groups made them suspicious in the eyes

of the state. Their relative wealth in comparison to their Russian neighbors made them targets,

because they were considered members of the bourgeois. As life became increasingly more

difficult throughout the 1920s, many Mennonites desperately tried to escape what had become a

living hell.

During the 1870s, Mennonites left Russia because they felt that the principles of their

faith were being threatened. The families of my great grandparents decided to stay in Russia,

despite the loss of their military exemption, because "things were going well there, so why

would they leave?,,10 However, when faced with the crises of the Civil War and its aftermath,

they were unable to remain and were fortunate enough to be able to leave. Their stories help to

illustrate that although many of those leaving Russia in the 1920s also left because they felt that

their religious beliefs were being persecuted, many Mennonites had no other option but to try

and emigrate. Unlike the mass immigration that took place during the 1870s, many Mennonites

in the 1920s left because their physical survival was no longer secure in Revolutionary Russia.

Historiography of UkrainianlRussian Mennonite Migration

The waves of immigration of the Russian Mennonites have been the subject of much

research. Mennonites themselves have published numerous books and articles regarding

immigration; the cultural identity for many Mennonites was shaped by their experience in Russia

and the waves of emigration in the 1870s and the 1920s were significant to the identity of the

10

(Adelaide Fransen 2013)

Schrag 7

whole group. Overviews of Mennonite history emphasize the Russian experience as a significant

contributor to the Mennonite identity today. "Through Fire & Water: An Overview of Mennonite

History" by Harry Loewen and Steven Nolt is the overview of Mennonite history that I used as

the backdrop for my study on the Mennonite experience specifically from 1917-1929. "In

Defense of Privilege: Russian Mennonites and the State Before and During World War I" by

Abraham Friesen discusses the Mennonite identity in relation to the state, and how it came into

question as Mennonites found themselves as an isolated minority in danger of losing their

"1 eges. II

pnVI

Interviews and diaries from Mennonites who lived through these periods of change and

their families are also valuable to research on this topic, providing an insight into the thoughts

and feelings of individuals. I used several of these personal sources that focused on the lives of

my great grandparents and their families, including a journal account of emigration written by

Margaret's younger sister, and notes from an oral interview I conducted with my grandmother

and her siblings about their parents' experiences. Oral histories are a valuable way to gain

infonnation about past events, and certainly are valuable in that they provide a personal

perspective and reflection on those events. In addition to taking notes during the interview, the

process should also be recorded. Appropriate research should be done beforehand and the

questions asked focused but open-ended to "encourage the fullest response possible to each

question." 12 Individual interviews are preferred, but for this project I interviewed my

grandmother and seven of her siblings, with three additional family members also present at the

11 Abraham Friesen In Defense ofPrivilege: Russian Mennonites and the State Before and During World War I (Perspectives on Mennonite Life and Thought) (Kindred Productions, 2006) 12 For additional information on conducting oral interviews and resources, see Barbara Truesdell, "Oral History Techniques: How to Organize and Conduct Oral History Interviews," Center for the Study of History and Memory, Indiana University, http://indiana.eduJ-cshm!oral_history_techniques.pdf. Schrag 8

interview. The primary speaker during the interview was the oldest sibling, Adelaide Fransen.

Throughout the interview, she spoke from notes she had about her parents' lives.

Non-Mennonites have also done significant research on the Russian Mennonites, their

research a testament to the influence that the Mennonite communities had in the settling of

Southern Russia and the formation of Russian identity. Dr. Sergei Zhuk in his book "Russia's

Lost Reformation: A Story of Mennonite and German colonization in Russia and Ukraine" and

in additional essays, explores the impact the Mennonites had on their Ukrainian peasant

neighbors in both the areas ofreligion and economics by using their own successful lifestyle as

an example. I3 The work of James Urry, "None But Saints: The Transformation of Mennonite

Life in Russia, 1789-1889" chronicles the Mennonite experience in Russia and explores the

changes that the Mennonites as a community underwent as a result of their colonization of

Ukraine, including the division within the group as a result of economic success. 14 This

economic success was analyzed by Natalia Venger in her book, "Mennonites as 'the Russian

Americans,' or Problems of Colonization and Modernization in the South of the Russian

Empire", in which she attributes much of the Mennonite success in the region to their

entrepreneurial spirit and well known "Protestant work ethic".15

\3 Sergei Zhuk Russia's Lost Reformation: Peasants, Millennialism, and Radical Sects in Southern Russia and

Ukraine, 1830-1917 (Washington D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2004); Sergei Zhuk, "'A Separate Nation'

of 'Those Who Imitate Germans': Ukrainian Evangelical Peasants and Problems of Cultural Identification in the

Ukrainian Provinces of Late Imperial Russia," Ab Imperio 3 (2006) 1-22

14 James Urry None But Saints: The Transformation ofMennonite Life in Russia, 1789-1889 (Pandora Press, 2007)

15 For a review ofVenger's work, see Sergei Zhuk, "Mennonites as 'the Russian Americans,' or Problems of

Colonization and Modernization in the South of the Russian Empire," Ab Imperio 3 (20 II) 30-40; For additional

research on Mennonite emigration from Russia to Kansas refer to Norman E. Saul, "The Migration of the Russian­

Germans to Kansas," Kansas Historical Quarterlies 40 (Spring 1974) 38-62 and for additional research on the

experience of Mennonites living in the Soviet Union in the 1920s Oksana Beznosova and Aleksandr Beznosova,

"The Religious Life of Mennonites in the mid-I920s through the Eyes of the Soviet Political Police: the Case of the

Fuerstenland Settlement," in History and Mission in Europe: Continuing the Conversation, ed. Mary Raber and

Peter F. Penner (Schwarzenfeld: Neufeld Verlag 20 II)

Schrag 9

My research also addresses these issues of economic prosperity and cultural identity, and

how the chaos of the Russian Civil War and the following years convinced many Mennonite

families that emigration was the only viable option. Using the stories of Henry and Margaret, I

hope to demonstrate how these larger events impacted individuals and motivated them to uproot

their families in an attempt to migrate. Specifically, the discrimination the Mennonites

encountered as a result of their German heritage, the negative consequences of their economic

success, and their being singled out as targets for anarchy during the Civil War allied to threats

for their physical survival, and it was because of their concern for physical survival as opposed

to spiritual survival, many Mennonites tried to emigrate from Ukraine during the 1920s.

Cultural Discrimination

Mennonites brought their German heritage with them to Russia. The commitment to their

culture even after migrating to Russia helped to keep the Mennonite colonists isolated and

naturally distinctive from native Russians and other ethnic groups. "The German language kept

them separate within a country", is how my grandmother described her parents' experience

growing up in Russia but speaking German on a daily basis. 16 One Mennonite woman growing

up in revolutionary Russia recalled that, "We were taught one hour of Russian every week,

otherwise all teaching was done in the German language.,,17 This insistence on maintaining their

language would have helped to contribute to the widening gap between the Mennonites and their

Russian neighbors - unwilling to "Russianize" themselves, the Mennonites would have been

considered foreigners, despite the fact that they had lived in Russia for generations.

16

17

(Adelaide Fransen 2013)

(Dyck 1998,14)

Schrag 10

It was their language that had naturally kept them isolated from their Russian neighbors

and it became a means of discrimination in the years leading up to and during World War I.

Since the Germans were the enemy of Russia, all German colonists were viewed with suspicion

by the Russian government and the Russian people. On November 3 rd , 1914, a policy decision

"prohibited the use of the German language in either public assembly or press".18 The following

year, another anti-German policy was declared, this time calling for German property owners to

"sell their holdings within eight months". 19 Although neither of these laws were truly enforced

because of the government's preoccupation with the war itself, the fact that anti-German

sentiment was turned into official, government policy with the goal of blatantly discriminating

against its own people demonstrates just how isolated the Mennonites and other German

speaking colonists were. Even though many Mennonite men served in noncombatant roles for

the Russian military during World War I, including Cornelius Enns, they were not seen as heroes

of war precisely because of the widespread hatred of anything German.

The German occupation of 1918 was a double-edged sword for the Mennonites. The

anarchy that had begun to erupt in the region as a result of the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 had

already begun to wreak havoc on Mennonite households. When the Germans occupied Ukraine

as a part of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in 1918, they brought with them some semblance of

stability and peace by helping to reduce the anarchy in Ukraine?O German soldiers shared the

same language and culture as the Mennonite colonists, and as a result, some soldiers were

housed and provided for by Mennonite families. This familiarity between the Mennonites and the

soldiers was considered a betrayal of Russia by the Bolshevik government after the Civil War

18

19

20

(Toews 1967,28)

(Toews 1967,28)

(Marrow 1983)

Schrag 11

ended; in the minds of many, the Mennonites had aligned themselves with the occupiers against

.

21

the RUSSlan government.

This feeling that the Mennonites had betrayed Russia was not completely unfounded.

Anarchy in Ukraine and the presence of the German Anny had contributed to the creation of an

organization known as Selbstschutz, or self-protection?2 The very existence of this organization

caused a split within the Mennonite communities of Ukraine, because the creation of a group of

armed Mennonite men, even with the purpose of self-defense against bandits and invaders, was a

violation of the Mennonite belief and commitment to nonviolence. "It's very controversial. It's

the position of Mennonites who are peaceful pacifists and it became a big issue.,,23 The existence

of the Selbstschutz during the war would lead to additional problems when the war had ended.

When Mennonite leaders appealed to the Bolsheviks after the war that Mennonites were a peaceloving group, the existence of the Selbstuschutz was brought up as evidence against that claim.

But even more of an issue was that in late 1918 and throughout 1919, parts of the Selbstschutz

had allied themselves with the White Anny, which had taken control of the region. 24 They

practiced military drills together and the Mennonite fighters were able to use White Anny

munitions and supplies. The presence of the Selbstschutz, in the eyes of the Bolshevik

government, represented not only the Mennonite ties with the German Anny, but also with the

White Anny resistance. Though many families did not participate in the Selbstschutz nor

condone its actions, "in the eyes of the government this association implicated the entire

Mennonite constituency of the South.,,25

21

22

23

24

25

(Toews 1967,42)

(Toews 1967, 26)

(Adelaide Fransen 2013)

(Toews 1967, 32)

(Toews 1967,32)

Schrag 12

Once the Civil War ended, it became increasingly beneficial for Mennonites to distance

themselves from their German heritage. To help Mennonite communities recover from the

devastation of the Civil War and the famine that followed, an organization called the Verband

der Mennoniten Stid-Russlands (Union of South Russian Mennonites) was created. Specifically,

one of their goals was to take advantage ofa decree issued by Lenin on January 4,1919, which

allowed committees to be formed to advocate for "anyone desiring exemption from military

service for religious reasons.,,26 The existence ofthe Selbstschutz during the Civil War would

make this feat incredibly difficult, but so would the task of making the VMSR a legal

organization with rights. It was suggested to the chairman of the VMSR, B.B. Janz, by the head

of the Ukrainian Cheka, Comrad Manzev, that the Mennonites could "consider [themselves] of

Dutch descent", despite the fact that they spoke German.27 The VMSR became the Verband der

BUrger Hollandischer Herkunft (Union ofthe Citizens of the Dutch Lineage) on April2S t\ 1922,

obtaining legal status as an economic association that would allow the organization to

communicate with the government in regards to reconstruction of the Mennonite communities

and breach the topic of emigration. Ironically, with the introduction of the indigenization policy

by the Bolshevik government in 1923, each national group was "to develop its culture and use its

language in government institutions within the group's national territory.,,28 However, by that

point the damage had been done, and while Mennonites were free to embrace their German

heritage, they were not permitted to express their religious beliefs.

The German language helped Mennonites stay connected to one another and their faith

when they migrated from Prussia to southern Russia. But their continued use of the German

26

27

28

(Toews 1967,53)

(Toews 1967, 76)

(Neufeldt 2009, 227)

Schrag 13

language contributed to a divide between them and their Russian neighbors. In the case of the

Mennonites, that alienation led to resentment which manifested itself in discriminatory policies

and behaviors during World War I and the Civil War. The native Russians "were angry that [the

Mennonites] were still speaking German. As a result those people thought the Mennonites put

themselves above them and so they entered their homes and wanted to kill them .,,29 Even though

the Bolshevik government eventually allowed ethnic groups to maintain their own culture, the

memories of persecution as a result of their German heritage was one of the key contributors that

led to the families of Henry and Margaret to emigrate. Though they would continue to speak

German at home and in their churches, they did not remain as alienated in Canada as they had in

Russia, and like many other families, they pushed themselves to learn English so they could

communicate with their new communities.

Economic Conditions

Beyond being separated from their Ukrainian and Russian neighbors because of their

German language and culture, as a whole Mennonites were also separated due to their economic

status. Mennonites and other German speaking groups were invited to settle southern Russia

precisely because the Russian government wanted them to set the example for economic

development in these unsettled provinces.3o The "Protestant work ethic" that attracted the

Russian government to the Mennonite people and the entrepreneurial spirit that Venger attributes

to the Mennonites resulted in significant economic success, so much that Mennonites have been

noted as "the most active participants" in bringing capitalism to southern Russia. 3l Certainly, the

efforts of the Mennonites helped many parts of the region, extending beyond just their own

29

30

31

(Adelaide Fransen 2013) (Zhuk 2004, 41) (S. Zhuk 2011); (Zhuk 2004, 45) Schrag 14

communities, but their wealth in comparison to their neighbors created the opportunity for

resentment to build. During the Civil War, this resentment came to the forefront of relations

between the Mennonites and their neighbors, their wealth making them targets.

Mennonites and other German speaking colonists had been invited to settle Southern

Russia specifically because their industrious nature had caught the attention of the Russian

government. Despite being colonizers of an unsettled area, these communities were able to create

and maintain a thriving economy. Mennonite businessmen were largely successful, bringing to

the region several useful industries that allowed the communities to grow and spread out,

developing more land as they went. They built their own agricultural machine factories, the first

in Southern Russia, which not only increased the productivity of the Mennonite community, but

the productivity of the entire region and the rest of the Russian Empire. 32

This success was a direct result from the Mennonite work ethic, which contrasted greatly

with that of the stereotypical peasant Ukrainian and Russian workers. Mennonites were

perceived to be determined, sober, and sensible. This hard-working culture set their communities

apart from those of their Ukrainian neighbors; their villages were described as "dirty,

impoverished, [and] ill-kept".33 So beyond setting the business example for the native peasants,

the Mennonites also set the example for cultural behavior that would lead to economic

prosperity. Those peasants who worked as laborers for the Mennonites and in their homes and

(S. Zhuk 2011, 36); One of the first families to own a machine plant was that of Abraham Koop. It is unknown if he was a relation to Henry Koop's family. 33 (S. Zhuk 2011,37) 32

Schrag 15

settlements were exposed to and influenced by this work ethic, and through that influence

aspects of the Mennonite culture began to spread and mix with other cultures in the region. 34

The importance of land cannot be overlooked when examining the conflict that would

arise between Mennonites and their neighbors; certainly the acquisition of large amounts of

fertile land contributed to the wealth of the Mennonite community. Most peasants who lived in

the countryside in imperial Russia did not have their own land, and the possession of land was

one of the indicators of a higher legal status. German speaking colonists formed a minority of the

population, but in the Ukrainian province of Ekaterinoslav, they "owned 12 percent of the

'productive' land" in 1890 and were given almost four times as much land as a Ukrainian or

Russian peasant was given. 35 However, it is important to note that while as whole Mennonite

communities were wealthier than other ethnic groups in the region, not all Mennonites were

equally wealthy. Land was not an infinite resource, and in 1865, approximately one third of the

Mennonite colonists were without their own land and were considered to be poor. 36

Henry and Margaret's two families represent the various levels of wealth within the

Mennonite community very well. Henry Koop grew up in a family that was very well off - "his

father owned a brick factory which employed a number of workers" and the farm that he grew up

on produced a wide variety offood. 37 Their true symbol of wealth, however, was the fact that

they owned a McCormick binder, an American piece of farming equipment. When the famine

struck Ukraine in 1921-1922, the Koop family was able to feed themselves, unlike so many

For detailed infonnation on how the religious influence of the Mennonites impacted other groups, refer to Sergei Zhuk, "The Stundists," Russia's Lost Reformation: Peasants, Millennialism, and Radical Sects in Southern Russia and Ukraine, 1830-19/7 (Washington D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2004) 77 and Sergei Zhuk, "'A Separate Nation' of ' Those Who Imitate Gennans' : Ukrainian Evangelical Peasants and Problems of Cultural Identification in the Ukramian Provinces of Late Imperial Russia," Ab Imperio 3 (2006) 1-22 35 (Zhuk 2004,45) 36 (Saul 1974); The lack of available land would have also been a contributor to the emigration of the 1870s and 1880s. 37 (Adelaide Fransen 2013) 34

Schrag 16

others. Margaret Enns was not so fortunate. Her family did not have their own land, and as a

consequence, they moved several times throughout Margaret's childhood, going wherever they

could get leftover land from relatives. Given the severity of the famine, without help from

Mennonite Central Committee, it is likely that their hunger could have become fata1. 38

Despite the variance in wealth levels between Mennonite families, even the poorest

Mennonite families were still able to hire native workers. Factories like the one owned by the

Koop family employed Russian laborers, and large farms also required peasant labor. Henry's

father employed several workers in his brick factories and even Russian natives to shake the

trees on his farm. 39 Even Margaret's poor family "had a cook, numerous housemaids to do the

housework, and nursemaids to look after the children", at least for a time.

4o

The difference

between an employer and a worker would have been difficult to overlook, and there are stories of

how the Mennonites "mistreated the Russians" that they employed and anecdotes suggest a sense

of Mennonite superiority over the uneducated peasants. 41 Research by scholars has also

attributed some of the conflict between peasants and the Mennonites to the "real economic

exploitation" that occurred. 42

When anarchy erupted in much of the countryside during the Russian Civil War, the

wealth of the Mennonites made them targets. Already targets because of their German culture

and language, their wealth made Mennonites the exact group that the Bolsheviks were trying to

38 Margaret mentioned having to pick weeds out in the woods to make a soup because of the severity of the famine. The Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) was created by North American Mennonites specifically to coordinate relief efforts to the conditions in Ukraine during the early 1920s. For additional information about the formation of MCC, refer to Harry Loewen et aI., Through Fire & Water: An Overview ofMennonite History (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press 1996) 249-250 and John Towes Lost Fatherland: The Story ofthe Mennonite Emigration from Soviet Russia, 1921-192 7 (Herald Press, 1967) 51. 39 (Adelaide Fransen 2013) 40 (Enns 1990) 41 (Enns 1990,3) 42 (S. Zhuk 2011, 39) Schrag 17

overthrow. Many were categorized by the government as either kulaks, "better-off peasants who

exploited poorer peasants", or byvshie, members of the old privileged classes who owned land or

had a higher social status. 43 Committees of the Poor confiscated land, animals, and machinery

belonging to Mennonites, and anarchist bands raided Mennonite settlements without mercy.

Letters written by Mennonites in 1922 revealed that these economic and material concerns were

one of their primary causes for emigration. Living in a land that no longer wanted them, unable

to restore their agriculture because of their lost property, for many, "there were no prospects for

future economic reconstruction. ,,44

The deterioration of the Mennonite's economic situation led the Mennonite leadership to

approach the Bolshevik government, with the hopes of trying to rebuild relations and reestablish

certain privileges that the Mennonites had held under the Tsar. Recognized as an economic

association by the government, the VBHH, under the leadership ofB.B. Janz, was able to ease

some of the economic hardships faced by the Mennonite communities. However, given their

experiences during the Civil War, many Mennonites wanted to explore the emigration option

rather than focus on rebuilding their settlements. Until it was shut down by the Soviet

government in 1926, the VBHH lobbied the government in order to secure exit visas. They also

worked with Canadian Mennonites, and who were then able to put pressure on the Canadian

government to open their borders to the Mennonites and worked out a deal with the Canadian

Pacific Railroad to pay for the passage. 45

(Neufeldt 2009,223) (Toews 1967,84) 45 For more information about the VBHH, its creation, and its role in Mennonite emigration, refer to Colin P. Neufeldt, "Separating the Sheep from the Goats: The Role of Mennonites and non-Mennonites in the Dekulakization of Khortitsa, Ukraine (1928-1930)," Mennonite Quarterly Review 83.2 (Apr. 2009) 226-230 and John Towes Lost Fatherland: The Story ofthe Mennonite Emigrationfrom Soviet Russia, 1921-192 7 (Herald Press, 1967) 74-75,81­

90

43

44

Schrag 18

"The Golden Age" for Mermonites was named as such in part because of the economic

prosperity that they experienced upon migrating to Russia. Dedication, hard work, and a knack

for irmovation were profitable for the Mermonite conununities. Even though the wealth was not

spread equally among the different settlements, the Russian perception of the Mermonites was

one of a well-off land owner with plenty of animals, machinery, and other material possessions.

This stark contrast between the Mermonites and the peasants was enough to create a divide

between the two groups. The anarchy of the Civil War, coupled with an increased dislike of the

Mermonites as a result of the German occupation and the Bolshevik cause against them, was the

catalyst for some poor peasants to tum against their neighbors. Certainly, some peasants had

been exploited by their Mermonite bosses and their resentment against the conununity as a whole

is rational; that built up resentment combined with a lack of land and food logically resulted in

the looting of property. Having been looted or their property destroyed, the lack of an economic

means to provide for themselves would have been one of the primary reasons for emigration.

The Anarchy of Civil War

During the Russian Civil War, the region in which many Mermonites lived was highly

disputed territory. The areas in which the Mermonites lived switched sides numerous times, but

not just between the two armies. As the Reds and the Whites struggled for control over the area,

anarchist groups also fought to establish control, terrorizing the countryside. These anarchists

fought against the Reds and the Whites, against each other, against the invading German army,

and against the people. Mermonites, with their wealth and German heritage, were targeted by

raids from all of these groups. The destruction of their settlements and communities was so great

during the Civil War, that many doubted that they would be able to recover, and so prompted

them to pursue emigration.

Schrag 19

Although Mennonites suffered at the hands of both the Red and White annies, it is the

anarchist Nestor Makhno that stands out in Russian Mennonite history as the "devil".46 Born in

1889 in a village north of the Molotshna colony, Gulyaypole, Makhno worked for Mennonite

landowners. Like other native peasants who worked for Mennonite landholders, he became

resentful of them as a result of feeling exploited. In 1908, Makhno was sentenced to lifeimprisonment because of his involvement in revolutionary activities. His return came in 1917,

when the Bolshevik Revolution resulted in his being set free from prison. Upon returning to

Ukraine, he built up an army of peasants and bandits, waging war against the Gennan anny and

the wealthy, including the Mennonites until he was defeated by the Bolsheviks in 1920. 47

The presence of Makhno's army roaming the countryside was a major source of concern

for the Mennonite communities, for several reasons. Most obviously, their physical wellbeing

was in danger. Makhno's men looted and plundered Mennonite fanns and houses, taking food

and valuables. The frequent occurrences of assault, murder, and rape were devastating - entire

villages were destroyed and abandoned as people fled for safety. Disease also took its toll in the

fonn of a typhus epidemic, which hit the Chortitza colony especially hard. According to some

estimates, between 1,000 and 1,200 people died in the epidemic of 1919-20. 48 Margaret's family

was threatened several times during these years. Her mother, Katherine, "was beaten with a

revolver when she refused to say where Cornelius [Margaret's father] was hiding.,,49 For the

Enns family, this threat of violence was the breaking point, and they fled their home and moved

to the larger village in the Molotshna colony for safety.

(Marrow 1983) (Toews 1967, 30-31) 48 (Loewen, et at. 1996, 248); (Toews 1967,39) 49 (Enns 1990,4) 46

47

Schrag 20

Although the physical damage caused by Makhno's annies was tragic, his raiding of the

Mennonite settlements also caused an ideological break within the Mennonite community. Since

Mennonites practice pacifism, they were easy targets for raiders because they were, in essence,

defenseless. But the damage being caused by the various annies and groups was too great for

many families to bear, and they gave up nonresistance with the intention of fighting in selfdefense. The Selbstschutz guard was created to help fend off attacks from the anarchists. Aided

as they were by the White Army, this guard was able to provide some form of defense for their

families. However, the one of the characteristics of the Mennonite identity is pacifism, and the

creation of this guard, even in self-defense, created a split within the Mennonite communities

themselves, never mind the consequences that they would suffer later as a result of the

Selbstschutz's creation. 50

Since the Ukraine was such disputed territory during the Civil War, the damage caused

by the Red and White armies also contributed to the destruction of Mennonite communities. Just

like the Makhnovists, members of the two armies raided and looted the villages, and houses and

other buildings were damaged during the fighting. 5 I The famine that occurred in 1921-22 was in

part caused by the actions of these various annies and bands. Not only did they requisition food

stuffs, but there are accounts of the Bolsheviks attempting to set up communal farms in the areas

they had under their control. According to the family interview, at one point Margaret's family

were forced into a communal lifestyle by the government, but that failed and her father was

50 \\!hen asked if Henry or Margaret's families participated in the Selbstschutz, their children said that they had not.

However, one of Margaret's younger brothers was shot in a gun accident. The gun was given to Katherine Enns for

~rotection, and it is possible it was given to the family by a Selbstchutz member.

I (Toews 1967,34)

Schrag 21

jailed three times because he was unable to "raise the quota of wheat or money that was

required" .52

Additionally, a major concern was that young Mennonite men were being conscripted

into the anny and forced to fight. One of the major goals of the Union of South Russian

Mennonites (what would become the VBHH) was to try and recover the Mennonite men who

had been forced into the Anny. Margaret's older brother, Abram, was conscripted into the anny

and as a result was not allowed to emigrate with the rest of the family after the Civil War was

over. 53 Henry Koop was also in danger of being pulled into the war. He was 13 or 14 when a Red

Anny officer commandeered Henry's horse and wagon. Forced to transport the officer to an

anny outpost, "he knew that he would probably lose the wagon and the horse if he didn 't do

anything". Sneaking away with his horse and wagon, Henry hurried back to his village, keeping

to the woods so that he would not lose his two valuable possessions and potentially his life. 54

The chaos of the Russian Civil war hit the Mennonite communities especially hard.

Many families lost everything they had, and in the period of transition that followed the war, had

no way of rebuilding their lives. The banditry that occurred forced many people, Mennonites and

non-Mennonites alike, out of their homes, creating a refugee situation in a region that could no

longer support them. The Civil War was the breaking point for the Mennonite community. It had

tested not only their faith and their commitment to the practice of nonviolence, calling into

question their identity as Mennonites, but it had put them in very real physical danger that cost

hundreds of people their lives. Even when the Civil War finally ended and order was restored in

(Adelaide Fransen 2013) (EMS 1990, 6) Contact was lost with Abram ' s family in Russia after 1932, when the famil y learned that Abram had tried to escape to China and been captured . 54 (Adelaide Fransen 2013) 52

53

Schrag 22

Ukraine, the violence that they had experienced was enough to convince numerous families,

including the Koop and Enns family, that it was time to leave while they still could.

Conclusion

World War I marked a clear turning point in the lives of the Russian Mennonites. These

were people who had been invited by the Russian government to help develop the Russian

economy more than a century before, and they were incredibly successful in doing so. That

success would contribute to their persecution beginning during the war and continuing as the

Bolsheviks targeted them as "land-owning exploiters". By the end of the Russian Civil War, the

entire Mennonite way of life had been broken or completely destroyed. The farms and businesses

that had kept their economy thriving had been ravaged by two armies and numerous anarchist

groups and bandits. Their homes had been destroyed and their valuables taken. Disease and

famine had taken the lives of many, weakening the community even further. Their identity as

pacifists had been challenged over the question of whether or not they should fight back in self­

defense. For the majority of the Mennonites, the golden age of prosperity that they had once

known had simply ceased to exist.

The process of emigration itself was not an easy task, and required just as many hurdles

to jump through. Limited visas were available, and large family groups wanting to emigrate

together were often delayed due to those visas expiring and the strict health requirements of the

Canadian government. Many, like Henry, were delayed in Moscow for several weeks while they

advocated for themselves in order to obtain the visas. Even having a visa was not enough to

secure their safe passage from Russia to Latvia - the heavily cramped trains were frequently

Schrag 23

stopped before they had reached the "Red Gate".55 The authorities that searched these trains

would look through and confiscate property, and even remove a passenger from the train,

preventing them from leaving the country. From there, they left from Riga to England, where

they were sometimes forced to stay for up to a year, waiting to be able to finish their journey to

Canada. As perilous as the journey was, conditions worsened for those Mennonites unable to

emigrate - the number of exit visas available to them dropped significantly in 1927 and was near

impossible after 1929.

56

Those unable to emigrate and who had not helped the Communist Party

became targets for Stalin's dekulakization plans, and many more Mennonites were killed or

imprisoned during this campaign to liquidate the kulak class. 57

Henry and Margaret were fortunate to obtain exit visas with their families. Henry left

Russia in 1924 and Margaret in 1926. Both would stay in South Hampton, England for a time

before finally boarding a ship that would take them to Canada. Margaret's family traveled aboard

"The Empress of Scotland", and began working the day after they arrived in Canada to begin

paying off their debts. The Koops wealth had allowed them to pay their own way, but they too

looked quickly to find work and a new community. Henry and Margaret met while participating

in a church choir in Kingsville, Ontario in 1928, and were married soon after. My paternal

grandmother, Ericka "Rickey" Schrag, is their fourth child of nine and was born in St.

Catharine' s, Ontario in 1939.

The "Red Gate" was a gate on the border between Russia and Latvia. It became a symbol of freedom for the

Mennonites. (Marrow 1983)

56 (Neufeldt 2009,231)

57 For additional information about the Mennonite situation after the Civil War, including information about

Mennonites participating in the dekulakization process, see Colin P. Neufeldt, "Separating the Sheep from the

Goats: The Role of MerulOnites and non-Mennonites in the Dekulakization of Khortitsa, Ukraine (1928-1930),"

Mennonite Quarterly Review 83.2 (April 2009) 221 and Colin P. Neufeldt, '''Liquidating' Mennonite Kulaks (1929­

1930)," Mennonite Quarterly Review 83.2 (April 2009) 259

55

Schrag 24

The events of 1914-1922 were the catalyst that forced my great-grandparents and their

families to emigrate, along with nearly 22,000 other Mennonite families escaping persecution.

The Mennonite community had faced the consequences of their continued use of the German

language and their culture, and they had much of their economic wealth taken or destroyed. The

anarchy that was rampant in Ukraine during the Civil War aggravated the situation even further,

making life in the newly established Soviet Union near impossible. A large part of their identity

had been attacked, both from inside and outside forces. With everything they had ever known

destroyed, it should not be surprising that many Mennonites held on to their faith, using it to

derive hope that their situation could improve. Despite that hope, the threat against their physical

lives had been too great to ignore, and it was to save their lives with the hope of rebuilding it

somewhere new, that many Mennonites took a risk and immigrated to Canada.

The events that took place in Russia were clearly crucial to the history and identity of the

Mennonite community, contributing to the strength of Mennonite presence in Canada and the

United States. Their plight brought together separate groups of Mennonites to form the

Mennonite Central Committee, which continues to aide and provide relief around the world. The

migration of so many people would have an impact on their new communities, their presence

impacting everything from the economy to the culture. More than their influence in Canada and

the United States as a result of their migration, the Mennonite story demonstrates the question of

identity that is relatable to all immigrants. Their identity was threatened by their experience, but

its survival suggests the strong ties to core values and a sense of community is not easily

destroyed. The Mennonites have shown that emigration is not about losing one's identity or

culture, but about its preservation and development, even in the face of tragic events.

Helena

b Jan. 1900

d. Mar. 1904

-­

Heinrich

b . Feb. 1906

d. Mar. 2000

1l1.

Aug. 1930

Helena

b. Jan. 1909

d. Feb . 1988

Anganetha

b. May 1894

d. Dec. 1976

1---1

1-

Margaret Enns

b. Feb. 1908

d. Nov. 2001

Jakob

b. Jun. 1911

d. Sep. 1913

Sara

b. May 1896

d. May 1971

-I

Jakob

b. Jun. 1914

d. Apr. 1982

Anna

b. Jui. 1898

d. May 1971

Heinrich Heinrich Koop

Sarah Klassen

b. Aug. 1869

m. Aug. 1891 b. Jan. 1872

d. Mar. 1949

I

d. Aug 1898

Katharine

b. Oct 1892

d. Jul. 1962

Margaretha

b. Sep. 1903

d. Feb. 1998

m . Feb. 1899

Heinrich

b.Aug. 1902

d. Sep. 1902

Helena Ediger

b. Oct. 1974

d. Jan. 1952

Lydia

b. May 1917

Susarma

b. Jul. 1898

d. Mar. 1986

'<

(1) S· t-'

~

CI.l

~

~

~

~

-

8

'0

0

0

_.

~

~

~

;:7

(") ~. -.

5. ..>

Q.,

~

1:1

::r:: (1) >

"'0

"'0

;J

()

\/)

\J)

N

~

aQ

g­

I

T

Abram :<:nns

b. Feb .904

d. ?

~'--J

Neil Elms

b. Sept. 1905

d. Apr. 1979

'

b. Oct. 1906

Maryi EnnS

Cornelius C. Eons

b

---­

. Feb. 1934

m. 1820

I

Margaret Elms

b. Feb. 1908

d. Nov. 2001

Kat

d. 1913

P

John Enns

b. Oct. 1910

Inns

--_ . Mav

---- 1903

-- --

Justina Friesen

b. ?

d. ?

d. 1918

i

Katharine Janzen

b. Oct. 1880

d. Dec. 1948

T

Justina Enns

b. May 1924

peJEnns

b. Sept. 1920

Maria Loewen

b. May 1854

d. Oct. 1936

Jacob Enns

b. Aug. 1917

Herman Enns

b. Jun. 1915

Katharine Enns

b. Feb. 1914

1S

Abram Janzen

b. Sept 1855

d. Jun. 1923

I

Maria Driedger

Abram Janzen

b. Feb. 1829 m. Sept. 1848 b. Jul. 1815

d. ?

d. Oct. 1881

m.1824

Agatha Klassen

b. ?

d. ?

John A. Driedger

b. 1791

d.1841

Anna Driedger

b. 1864

d.1889

-

Abram Driedger

b. 1821

d. 1899

Comelius H. Elms

Katherine Driedger

b. Aug. 1853 m. 1876

b. 1855

d ]"". 1 8 8 9 l d.1889

Katherine Froese

b. 1829

d. 1867

Maria Friesen

b.1793

d. 1823

Abram Driedger

b. in Prussia

d. in Prussia

Vl

§

trJ

Vl

c:

~

n

o

3

0...

::l

p:l

(1)

ti.

::l

::r

~

;ri

o

-,

(1)

S·

......

L'

(1)

(Jq

0...

(1)

::J.

Cj

......,

::r

(1)

0\

N

p:l

(JQ

~

()

r:/)

I

I

David Schrag

b. Jan . 1968

Jacque Schrag

b. May 1992

Adelaide Fransen

Elfrieda Funk

b. Sept. 1933

b. March 1937

Lydia Friesen

b. July 1935

Ann Hunsberger

b. Jan 1944

Margaret Enns b. Feb. 1908 d. Nov. 2001

Helen Koop

b. Nov. 1942

p 1930

Henry Koop

b. Dec. 1940

I

m. Au

Mark Schrag

b. Mar. ] 969

Derek Schrag

b. Mar. 1995

m. Oct. 1922

div. 2002

Alfred Koop

b. Dec. 1948

Matthew Schrag

b. Apr. 1999

Sheri Wright

b. May ]972

Ericka Schrag m . Au o 1965 Myron Schrag

b. Feb . 1939

F

b. Jan. 1937

Henry H.

Koop

b. Feb. 1906

Step hen Schrag

b. Sept. 1972

Ester Neufeldt

b. Aug. 1950

(1)

(1)

~

>---1

.....

a

'Tj

'"0

1'\

o

o

(1)

~

.....

.......

(Jq

e;

~

0­

§

'<

~

(1)

::r:

C/)

()

N

-..I

~

::T"

....,

Schrag 28

Appendix B: Interview Questions and Transcription

Date ofInterview: February 23, 2013

Interviewees: Adelaide Fransen, Ester Nuefeldt, Pete & Fritz Funk, Rickey Schrag, Henry Koop,

Helen Koop, Ann & Moe Hunsberger, Alf & Liz Koop, Mark Schrag 58

Interview Questions:

1. Biographical Information

a. What were their (Henry and Margaret) legal names?

b. When were they born?

c. Where were they born?

d. The names of their parents and their birthdates

e. Dates of death

2. Logistical Questions about Journey

a. When did they leave Russia?

b. Where did they leave from?

c. When did they arrive?

d. Where did they arrive?

3. Under what circumstances did they leave Russia? Did they plan well in advanced or did

they leave in a hurry?

4. What were their causes for wanting to leave?

a. How did they and their families react to the Russian Civil War? Were they

affected by it?

Adelaide was the primary speaker during the interview. Throughout, she referenced notes she had from talking

with her parents in 1996.

58

Schrag 29

b. Did they leave as a reaction to the Civil War?

5. What kind of life were they leaving behind?

a. Were they peasants or land owners?

b. What was their social status in terms of wealth?

c. Were they connected to the community?

6. Why did they leave when they did and not sooner?

a. The first wave of emigration happened during the 1870s, why did they not leave

then?

7. Did their reasons for leaving relate to their Mennonite faith?

a. Did they feel safe practicing their religion?

. TranscnptlOn:

. . 59

Intervlew

Jacque: This is for my history capstone and my honors thesis that I need to have done to

graduate. What I'm doing is looking at my great-grandparents, your guys' parents, emigration

from Ukraine to Canada. The questions that I have are focused on that. What I'm doing with that

information is putting it into broad historical context because there's quite a bit of research

already done on the general reasons why Mennonites emigrated during this particularly time. So

that's what I'm doing. So to start with, I have biographical information questions: legal names,

birth dates, birth place.

Adelaide: I have some of that yes. Are you talking about your great-grandparents?

Jacque: Yes.

Adelaide: Henry H. Koop was born in Alexanderkrone, South Russia or you could say the

Ukraine. Molotshna. I don't know if you need that.

Jacque: I'd rather have more information than not enough.

Adelaide: Henry H. Koop was born in Alexanderkrone, South Russia or you could say the

Ukraine. Molotschna. That's where he was born. Your great-grandmother, Margaret Enns, was

her name, her maiden name. E-n-n-s, was born in the village of Schroebrun.

59 Given the number of people present during the interview, interjections to ask questions, clarify points, or spelling

were frequent. These were left out of the transcription of the interview, as were small side discussions that took

place that were irrelevant to the topic. When large sections have been removed , it is indicated by [ ... ]

Schrag 30

Mark: What year?

Ester: Her name was Margaret, not Margareta.

Adelaide: 1908. Henry was 1906. Was else did you need? She moved around a lot. Do you want

me to say some of the notes that I have on her? A little bit more about her?

Jacque: Yeah!

Adelaide: Her grandparents lived in the middle of a 6 farm village. Mom's parents lived across

from the school. When Mom was three years old, she moved to Dovilyoucanava, where her

father bought a general store, a thousand miles by train from where she was born, from

Schroebrun. She moved within the city, I guess several times, across the tracks she says. And

then in 1915-1916, she moved to Schroenfeld and she started school at the age of 7. But anyway,

you don't have to write this down but let me clarify what happened. He actually went broke. He

and a friend started this general store. They just went broke. Okay. 1915 moved to Schroenfeld.

Her father took over a farm. I think he farmed, but he didn't own the farm, but I think he ran the

farm . In 1917 they moved to Blumenfeld and moved in with their grandparents, the Jansens.

They lived there for a few months until her father came home from the Caucasian mountains. He

had been conscripted and he worked as a secretary in the Army, I guess.

They moved back to Schroenfeld to grandfather's farm until 1920. Government ordered a

communal lifestyle. And they lived with Russian peasants in the same house and farmed

together. This experiment did not tum out well and so it was disbanded. So at that time, I guess

for a very short time, there was some kind of experiment going on.

Bolshevik bands came and plundered houses and villages. These were difficult times. Now, this

was an interview I had with my mother, so these are the things I'm telling you now from my

notes. I just made notes; I didn't write them out in full sentences. Bolshevik bands came and

plundered houses and villages. These were difficult times. They were forced to flee to

Petershager. Where, and you don't have to write this down, Uncle Pete was born and they lived

on a farm which had belonged to her great grandfather. Her father was elected as a mayor which

was not always a glamorous position. Are you keeping up with me?

Jacque: Yes. It is being recorded so you don't have to worry about the notes too much.

Adelaide: Again I'll talk about my mother, your great-grandmother. Her father had to go to jail 3

times because he could not raise the quota of wheat or money that was required.

From 1920-24 they lived in Ladekopp where they had an auction and October 1926 they left

Russia. They spent 6 and a half months in England at Atlantic Park which was South Hampton,

because of health reasons. This had to do with eyes.

On May 28th, 1927 they arrived in Canada.

Ester: They arrived in Quebec City.

Adelaide: From Montreal to Kingsville they took to train. How they got to Montreal, I don't

know. They took the train and they were taken in by the John Dyck family, which was a relative

of theirs. The next day, and there was no time to recuperate from jetlag, mother began her first

Schrag 31

job in the Cowan household. She spent two years there. She knew no English when she started there, except for "Yes" and "no" and "good day". And she also worked in Limington at Diana Sweets, which is a restaurant. She also worked at Kimberley's for 8 dollars a week. Which helped pay off the "reiseschuld", travelling debt. I don't know how much you know about the Mermonite immigration during the twenties. The CPR, Canadian Pacific Railway Company, sponsored our Mermonite people, which they later had to payoff. Difficult time that they, the people who were assigned to collect this money, often had doors slammed on them for some reason or other. A lot of them didn't have the money. They came around close to Depression times and they had a hard time finding jobs. Fritz: Mother still had a debt when they got married and that was two years later, right? Ester: The CPR got involved because there were Mermonites in Canada already from the 1870s immigration. Adelaide: In 1928, Henry Koop arrived in Kingsville from the West. They both sang in the choir. They remember meeting at a wedding and they were the wirmers of a circle game and were lifted high up on chairs. Their first child was born on September 25, 1931 and was buried in Ruthom. They moved to Jordan and then to Khris Fretzed. That was a farm where they worked and then they went back to Jordan. They worked at Whispers for three winters and earned $25 a month. Adelaide and Lydia were born during this time 1933 to 1935. In 1936 they moved to a farm in St. Catherine's, which is where they stayed. So that's all I have up to that point, but we can give you more details up to that point. Jacque: Can I get her parents' names? Adelaide: Cornelius and Katherine. Jacque: What was the last name? Ester: Erms. Fritz: Her maiden name was Janzen. Adelaide: I can give you more genealogy later. Ester: If it would be on value to you, I didn't think about bringing it, but I can scan their papers, the log of the ship that mom came on. Jacque: That would be helpful. Adelaide: What was the name of the ship? Liz: The Empress of Scotland. Ester: Yes, the Empress of Scotland. I'm pretty sure, it will say on the information that I send you. Adelaide: Do you have anything to add about what mom might have said about their journey or their time in Russia? Schrag 32

Rickey: Well you didn't talk at all about the famine.

Adelaide: That's right, I didn't. I do have those notes somewhere else.

Rickey: First of all, and you didn't say this, my mother's family were always the poorer family

because my grandfather was not a,land owner. And in villages that family always got left over

land or he was a storekeeper and didn't make a good go of it. He wasn't a good businessman. He

was a real people person. He led choirs in church, later on he was on this committee that helped

Mennonites come to Canada, but he was not a business person or a farmer.

Adelaide: He was not a farmer.

Rickey: He was not a farmer. And yet it was a large family. My mother's family was a poor

family. Anyways I was going to start in on the famine. What years were that? That's what I don't

know.

Jacque: Which one?

Adelaide: Early 1920s.

Rickey: Because they didn't own, my dad's family would have had a lot of chickens they could

kill, but mom's family was very poor and very hungry. Mom talks about going out into the

woods and getting weeds to make a soup. Mom talked about that kind of stuff to me.

Adelaide: They had their last piece of bread and then the MCC moved into the Ukraine and

helped out with a soup kitchen. So that really kept them, now Dad's family was not affected.

Ester: It was quite a different lifestyle. The Famine was in Russia, you'd be able to look up,

because it was all of Russia.

Rickey: This would have helped prompt the Ennses to move to Canada, to emigrate. Not just the

famine, the persecution, but also the fact that grandpa didn't have land and didn't have anything.

Those are the things that prompted that family to want to move

Alf: Yes. The famine was partly government induced. It was partly because of the government's

policy that were being introduce into communal practices, and it was because of these the famine

actually started. It wasn't only the conditions of the

Alf: Absolute yes. The famine was partly government induced. It was partly because of the

government's policies that were being introduced to communism, to communal practices, that the

famine actually started. It wasn't only the conditions of the war, but it was the introducing of the

communal styles. It was also because of the anarchy that was rampant there. I guess that's where

Adelaide said that the Bolsheviks were a part of the problem. It was mostly anarchy and the

bandits that were roaming the country. And all of these conditions were the reasons that the folks

that wanted to emigrate, because of the banditry and the lawlessness, and Wild West conditions

that were going on. The other thing would have been because of their faith was being tested and

their religion was being restricted because what they could do and teach and preach in their

churches and schools.

Schrag 33

Adelaide: The Russian peasants were jealous of the Mennonites because the Mennonites had

done so well on their land, and maybe replaced them [the Russian peasants] and they were doing

well. That was a big part of why they left.

Adelaide: You will read about the red army and the white army, and all of that, we don't need to

tell you about all of them.

Jacque: I know the historical background, but were they affected by it?

Rickey: Oh yeah.

Jacque: And in what way?

Adelaide: They were forced to give their best horses. They were forced to bring provisions to the

front. Dad, as a 16-17 year old, took a team of horses to the front with provisions for the Army.

That was quite an adventure.

Jacque: Which one, because there was also Makhno? You have the red army, the white, and him.

Which one did they have to help?

Rita: They didn't have to provide any provisions for Makno, because he just took whatever he

wanted from whomever.

Rickey: He raided.

Rita: When the Red Army went through, then they had to provide food for them. When the front

changed and the White Army went through, they had to do the same thing for them. It could have

been either one because the front changed many number of times right through that area where

they lived.

Adelaide: Henry H Koop, and there was a whole long line of them.

Ester: Heinrich Heinz, wasn't that his name, really?

Adelaide: Was born in January 28th, 1906 and Alexanderchron, Molotchna Ukraine. His parents

were Heinrich Heinrich Koop and Helena Adelaidega. He had a happy childhood. His mother

decided that he was ready for school and so he went to school at age 6 only to be sent home

because he was too young. She only had two boys and she was the second woman in the family.

Ester: The heir and the spare

Adelaide: He spent 6 years in elementary school, Dorfschule,

Ester: Which would be like a village school.

Adelaide: After which his ambitious mother pushed him to get to high school. He failed his first

year because of lack of preparation. He was not ready for the challenges of a higher course. His

bout with typhoid fever and the fact that he had to miss 6 weeks of school could also have

contributed to this. It was rampant in these families and many people died in those years. Dad

confessed that he resorted to a little cheating by copying the work of his good chum, a very

clever student who set next to him.

Schrag 34

Dad's favorite subjects were math and geography. He enjoyed playing ball and especially

swimming. He had skating on the river. He was fortunate enough to have a very good pair of

skates. They were very well off. Alexanderchron had 40 full farms. It had a church, a drugstore,

a mill for grinding wheat, and a doctor.

Rickey: The church is still there. I've been there. It's now Ukrainian Greek orthodox. But it is

being used a church.

Adelaide: His father owned a brick factory which employed a number of workers. Dad grew up

on a large farm which grew wheat, hay, oats, barley, com, and sunflowers. There were fruit trees

such as plums, grapes, which were dried for the winter. They employed Russian natives to shake

the trees. Dad and friend, Herman Dyck, built a tent and stayed and slept there to prevent

thievery of the plums. Other workers were employed to help with the harvest. His father was a

progressive, prosperous farmer. They owned two blinders, one of which was a McCormick

binder from the US and was pulled by horses. One person drove the horse, while the other

looked after the binder.

Rickey: That spoke about their wealth; that they could bring American machinery to Ukraine.

Adelaide: As conditions worsened more primitive methods were used. Dad talks about his father

having remalTied. The family was not spared illness. Dad remembers how ill he and other

members of the family were during the typhoid epidemic. Sarah was a nurse and came to nurse

the family. They were not allowed to eat and became very weak. [... ] During the later years, Dad

remembers the condition economic and politic deteriorated and many people suffered illness,

starvation, and violence. Even to the point of being killed and dying. The Koop family was

spared. MCC brought food for distribution to the needy but the Koops were able to look after

themselves.

Ester: What were the circumstances when dad took the horse, when Makhno was in the village?

Alf: Dad kept the horse, and I'm not sure what he was actually transporting. But he had to

transport and officer, I think it was for the Red Army, 6 or 8 hours away from the village and he

was supposed to take this officer to this outpost or whatever. When he got there he knew that he

would probably lose the wagon and the horse if he didn't do anything. So when the officer went

into the outpost and left his briefcase or his papers on the cart, and your grandfather threw them

on the ground and got out with the horse back to his village. That way he saved his horse, his

wagon.

Rickey: And his life.

Ester: I think that's the same story and they went after him. So he was hiding in the woods or the

forest on his way back.

Rickey: I heard that he rode back all night to get back with these horses. I thought he was 15 or

16.

Alf: It probably would have been about 1918 or 1919, those were the worst years. Anarchy was

worse in 1919, the revolution was in 1917, and all of that took place in the next years. So he was

13 or 14 when this happened.

Schrag 35

Adelaide: As far as their emigration is concerned. Rickey: Why did that family decide to go? Adelaide: I don't have that. Maybe you people can help you out here. I remember some stories. Ann: Didn't they take over the farm? They took over their farm and they had to leave, right? The communists took.

Alf: They actually sold their farm. We know the people that actually lived in that place after they

left. [... J They had bought it for very little. They had practically left without getting any money

for it. I don't know they left. It was probably an accumulation of circumstances, and I think I

talked to Dad or grandpa many times and got the sense that it was as much for the religious

persecution as it was for their faith, their church, and school, as much as it was for the economic

conditions. Economic conditions were very poor. Conununism was coming in. The economic conditions were one thing, but it was equally as much because of the persecution of their faith. Adelaide: Do you know the story of them having an auction? And I think they all went towards Moscow and dad stayed in Moscow ... why, exactly? Was it because of health or. ..? Ester: Dad stayed behind in England for a year, not in Russia. He had to go to Moscow by himself for medical reasons. Adelaide: in Moscow, he did talk about going to see the Circus and I want to say Opera. Rickey: He was there by himself. Adelaide: By himself. And he was what? Does anybody have the date of emigration? Rickey: 1926 Alf: He was advocating. 1925. Ester: '26 when mom moved. Alf: December of '24 when he was in England for Christmas. So it was in January '25, so he wasn't quite 18 yet. Adelaide: Can you imagine then the large city of Moscow? And he had time to spare there. I guess he was there because of his eyes. Rickey: I think so. Well, no, just a minute. He had this spot in his lung, and I'm thinking now that it was part of his typhoid. That's why he wasn't conscripted into the army. Otherwise he would have been. Adelaide: But he was too young for the army. Ester: Would that have been part of it, Alf? Being conscripted. Alf: Yeah, definitely. I think that's why they got him out. Adelaide: Why was he in Moscow? Schrag 36

Rickey: To get special papers. Alf: I know it was to register for his papers. His papers weren't in order. He needed to get it straightened out and in order. It wasn't nearly as long as he was in England. It was only a few months, in England it was that whole year. Adelaide: So after he was released in Moscow and got as far as England, he was in England because of his eyes? Rickey: Canada wouldn't let them come if they weren't healthy. Adelaide: Dr. Durry, a Canadian doctor, would come to Russia and examine people before they even left. Rickey: Canada was not going to take anybody sick. Adelaide: That information is in other places. Ester: Most Mennonites talk about the Red Gate. Adelaide: that's the boundary. Rickey: In Riga, Latvia. Ester: They would have passed through there on the train. When they first crossed into Latvia. Adelaide: They would go as far as the port and where was the port where they took off from? Anne: Riga. [...]

Adelaide: It's the capital of Latvia. What's the name of the Port? I forgot.

Alf: It was Riga. The border had no city. The border between Latvia and Russia was where the

Red Gate was, there was no real city there.

Adelaide: Riga is where many people were detained as well because of health reasons. All the

way along, they talk about delousing. I can't say that about our parents, but a lot of people were

deloused.

Rickey: They were living in box cars; they were living in terrible conditions. They picked up all

kinds of germs and diseases.

Adelaide: Do you know zwieback are? They would take those on their long journey. That

journey would take months sometimes.

Alf: We just googled Riga and it says right here that Riga is a sea port and a major industrial and

cultural city on the Baltic Sea region. It's a large sea port.

Rickey: From there they went to South Hampton, England. And this is all because of the

Canadian government not wanting to take sick people.

Schrag 37